by Alvaro Zinos-Amaro

Los Angeles Review of Books

March 10th, 2014

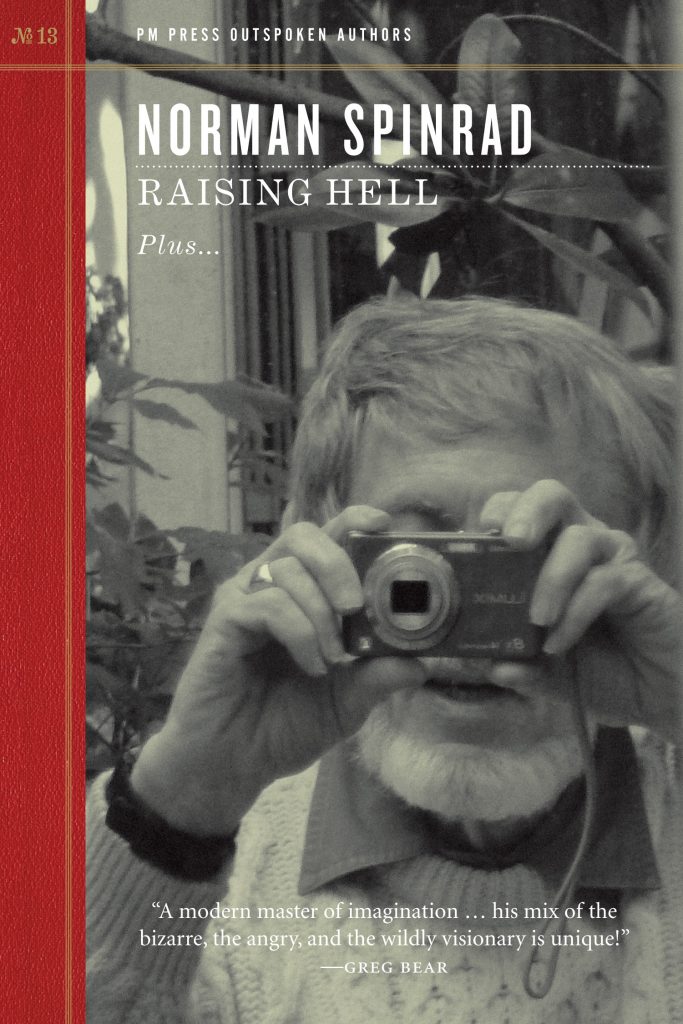

NORMAN SPINRAD’S WORK has, over the last fifty years, elicited responses that range from “depraved, cynical, utterly repulsive” (Donald Wollheim) to “delightfully bonkers” (Thomas M. Disch) and “extraordinary” (Ursula Le Guin). Perhaps my favorite characterization of Spinrad is by Isaac Asimov, who, in somewhat of an understatement, observed that he “constantly displays the courage to be different.” I’d like to illustrate this career-defining search for innovation by examining five of Spinrad’s key novels, ranging from the 1960s to the 1990s, all newly available courtesy of ReAnimus Press.

Revisiting Spinrad’s work, I was struck by his chameleonic shifts of voice, style, and pacing. Consider, for example, the following two passages:

Oh, you so right, baby! So here I am, dragging my dick along First Avenue, right back in the whole dumb scene I kissed good-bye six years ago. Sara, you stoned when I get there, I’m gonna beat the piss out of you, so help me.

Bug Jack Barron

Against the will of self-esteem’s desire, I could not fail to acknowledge that the true chasm between us lay both below and beyond the moral realm of ethical esthetics. Indeed, her ruthless dedication to her one true grail, proceeding as it did from a single absolute axiom to an entirely unwavering pursuit of this axiomatic higher good, might be said to be at least formally superior to my chaotic involutions.

The Void Captain’s Tale

I was also surprised to learn that Spinrad, who is often reductively labeled a “New Wave” writer because of his association with Michael Moorcock, New Worlds magazine, and other writers like Thomas M. Disch, Samuel R. Delany and Pamela Zoline, got his start by publishing three stories in John Campbell’s Astounding (renamed Analog by the time Spinrad appeared in its pages). Those three pieces, gathered with other early notable work in the collection The Last Hurrah of the Golden Horde (1970), reveal a solid grasp of relativistic space travel and other rigors of “hard SF” that one doesn’t normally see associated with Spinrad. They also highlight thematic preoccupations that reappear often throughout his fiction: displacement and alienation, which for example lead Ben Ezra to muse that life aboard a starship is “fit only for Gypsies and Jews” (“Outward Bound”), and questions of ethical responsibility, ontology and solipsism (“Sometimes I forget that I’m crazy, and then I become crazier. A neat paradox, no?” asks Miklos in “The Last of the Romany”) .

Given Spinrad’s wide spectrum of literary approaches and broad philosophical concerns, the question becomes: how do we evaluate the work in any meaningfully unified way, rather than as isolated or discontinuous experiments in form? I would suggest that perhaps the most apt criteria we can use are Spinrad’s own ideas about what science fiction (SF) is and does. But even here, we must tread carefully. Spinrad has granted many interviews throughout his fifty years in SF, and he’s also written extensively as a critic and reviewer. His theoretical ideas about SF, therefore, are often as complex — and embattled — as his fiction. Rather than an exhaustive analysis of all these positions, I’d like instead to focus on a fundamental notion to which he has returned several times. When asked about his writing process in a 1978 interview for CONTACT: SF A Critical Journal of Speculative Fiction, Spinrad began his response by saying: “The idea, I guess, to me, the essence of science fiction is the psychological interaction between consciousness and the environment.” In one of his “On Book” columns for Asimov’s Science Fiction, Spinrad returned to this formulation in 2005, albeit in far less tentative terms: “… all true science fiction is centered on the interaction of the external surround — physical, political, cultural, linguistic, anything and everything — with the lives and consciousness of the characters. If it does this, and there is any speculative element in the externals of the fictional universe at all, it is true science fiction, and if it does not, it is not true science fiction. Period.” Do Spinrad’s novels, then, succeed according to this view of SF?

The Men in the Jungle (1967), Spinrad’s third novel, offers us a tale of egomania masquerading as blood-drenched revolution gone horribly awry. Bart Fraden, Sophia O’Hara, and General Willem Vanderling flee the crumbling Belt Free State and program their ship’s computer with certain measures of “revolutionary potential — dictatorial government, economic setup, rigid class lines with high social tension, and about a hundred others” to locate a planet that will be ripe for takeover. The power hierarchy on their eventual destination of choice, Sangre, turns out to be nightmarish beyond their wildest imaginings: the ruling Brotherhood of Pain breeds various classes of humans for the purposes of law enforcement and torture (Killers), food (Meatanimals) and reproduction (women). The Animal slaves in turn oppress the native insectoid culture by keeping the “bug Brains” that control the worker insects docile through permanent inebriation. The three Earth protagonists attempt to instigate a revolution by shocking the lowest Animals out of their genetically and environmentally-enforced stupor through a combination of ultra-potent, highly addictive drugs, demonstrations of guerrilla warfare tactics, and vague anti-totalitarian ideals.

The chronicle that follows is unrelentingly gory, with countless severed limbs and decapitations, infants being roasted and eaten for pleasure, scorched-earth massacres, and all-around Killer/Animal/Bortherhood carnage. Add to this the frenzied yelling of “KILL KILL KILL!”, a mantra repeated with bludgeoning regularity. If this sounds upsetting, it is. The novel’s physical violence reaches orgiastic, histrionic proportions, mirrored by the psychological disintegration of the three main characters who, needless to say, succumb to their own conflicts. And yet, despite the slaughter, the novel confronts us with a fascinating planetary ecosystem and embeds its horrors in a binary-based philosophical system that not only perversely justifies pain but makes it necessary for someone else’s pleasure. Then, too, the book’s Vietnam-inspired political musings are rendered with gusto and depth, as when, about two-thirds of the way through, Braden lays out in detail the four stages of a classic revolution.

Anchoring the plot is Braden’s ongoing appeasement of his own conscience through increasingly tortured justifications for his heinous, ultimately opportunistic deeds. Despite some of the novel’s creaky, hyperbolic prose, and its dated reliance on coining new words, like “lasecannon,” “computopilot,” “synthmarble,” or “snipguns,” by bashing old ones together, its savage deconstruction of political hypocrisies, and its almost gleefully obsessive commitment to working out every last consequence of its SFnal premises, still pack a contemporary punch. The characters’ consciousness is in dialogue with the fictional environment, and technology acts as a devastating projecting conduit for their morally-compromised psyches. The bloodshed due to Braden and his two cronies, seen this way, is not a heavy-handed warning against the perils of technology as much as the crystallization that said technology manifests our own inner demons, and that, simply said, bad can always get worse.

More widely controversial because of its raw sexuality and numerous expletives, Spinrad’s next novel, Bug Jack Barron (1969), placed him center-stage for some readers while relegating him to the sidelines for others. I will not attempt here to summarize the novel’s labyrinthine plot involving cryogenics, television, and politics, but will simply note with amusement that it is perhaps the only SF novel whose Wikipedia summary concludes with “The two [Jack Barron and Sara Westerfeld] celebrate by having oral sex.” David Pringle selected Bug Jack Barron as one of his Science Fiction: The 100 Best Novels, and commented that though its plot is “very conventional” (an assessment shared by SF historian and editor Mike Ashley), its “surface,” meaning its “media landscape” setting and “breathless slangy” style, are really what matter, and are mostly very effective. Academic Roger Luckhurst describes the novel’s style as a “stream of consciousness … designed to capture the shock and disjunction of televisual images.” In a way, Spinrad’s technique here anticipates later mainstream attempts to capture our modern experience of fragmentation via media, as for example in novels by Don DeLillo or in David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest. Nevertheless, the novel’s central activities remain political: scheming, counter-scheming, corruption, the manipulation of public perception. Purportedly because of its obscene content, the large British retailer W. H. Smith pulled it from its stock by the time the third issue of its serialization in New Worlds, March 1968, appeared. Mike Ashley has speculated that such a decision may have had more to do with other content in that same issue, such as Langdon Jones’ “The Eye of the Lens” stories. One of several faults that Joanna Russ found with the book was that it was “romantic” and “youthfully bouncy”; Pringle, too, warns us that it is “occasionally sentimental.” Of the five novels in question, I think that time has perhaps been least kind to this one: reality has in many ways mirrored or even superseded Spinrad’s socio-cultural extrapolations (for example, the legalization of cannabis, at least in some States), weakening its SF vein. Nevertheless, one can see how it broke new ground at the time.

Spinrad’s next, highly polemical novel, The Iron Dream (1972), exists in more of an extrapolative bubble, and is therefore largely immune to subsequent developments in both the SF field and reality at large. In SF criticism pertaining to time travel stories the phrase “jonbar point” is sometimes used to refer a “crucial forking-place in Time … most works of Alternate History develop their changed future from a single explicit or implied jonbar point” (The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction online). The Iron Dream relies on such a jonbar point, namely Hitler’s emigration to the United States in 1919, followed by his career as a pulp SF illustrator and writer. Spinrad’s interest, however, doesn’t lie in the particularities of this alternate time-stream, but rather with the nature of commercial SF itself, and how easily it can subvert and subsume resonant symbols into a kind of fascistic sword-and-sorcery hero-quest mythos. To explore these ideas Spinrad presents us with his faux-Hitler’s novel Lords of the Swastika, which comprises The Iron Dream’s main text.

Purportedly written by a hack writer, Lords of the Swastika stays true to its propagandistic vision and showers us with page after page of jingoistic, eugenics-obsessed purple prose and phallus-centric power fantasies. The story is episodic and of escalating grandiosity. We are told of the rise to power of “genetic true man” Feric Jaggar, who becomes head of the Human Renaissance Party, triumphs in a series of character-testing perils at the hands of the leather-clad, motorcycle vagrants Black Avengers (a transposition of Hell’s Angels) and thereby discovers he is the rightful heir to the glorious weapon Great Truncheon of Held. Wielding its mighty steel and cutting down all who oppose him while “riding the juggernaut of destiny,” Jaggar becomes the Supreme Commander of Held, a role that allows him to establish Classification Camps to strictly test for hereditary purity and enact the ultimate eradication of the genetically impure Zind. Like The Men in the Jungle, this novel contains its share of gore and carnage, but here it is described unabashedly, even lovingly, as would befit Hitler’s fictional alter ego. The novel is followed by an “Afterword to the Second Edition” by the fictional Homer Whipple that peals back the narrative’s trashy curtains to reveal its core of highly sexualized racism.

What to make of all this? Certainly the audacity of the novel’s premise, and the care with which Spinrad executes it, are to be applauded. But for me the reading experience was a tense and tiring affair. On the one hand, Spinrad is tempting us to enjoy the story on a gut level by pushing precisely those mythological buttons that so often evoke a sense of wonder and suspend our disbelief. On the other hand, I kept reminding myself that any seduction by or even transitory alliance to Jaggar’s ideals and mode of conduct would be morally repugnant. I therefore found myself remaining at arm’s length throughout, approaching Jaggar’s progressively self-aggrandizing hero rites by way of Hitler’s overblown, redundant prose with chilly, intellectual detachment. Ursula Le Guin, in a 1973 Science Fiction Studies review that praised the novel’s high stakes while questioning whether more wouldn’t have been gained by a shorter text, zoomed in on this “staggeringly bold act of forced, extreme distancing” that Spinrad has achieved. Thomas M. Disch, in a memorable turn of phrase, recommended The Iron Dream as a consideration of the “fascist lurking beneath the smooth chromium surface of a good deal of sf.”

R. D. Mullen, on the other hand, wrote in a 1978 capsule review that The Iron Dream “ceases to be funny after the first few pages, and therefore becomes identical with what it is parodying.” I think he’s missing the point, in that Spinrad’s main purpose doesn’t appear to be humorous per se. Sean Kitching, in a recent retrospective on Spinrad published at The Quietus, analyzes The Iron Dream on three levels: satire, the author’s self-explication of Nazism, and in terms of Anti-Oedipus symbolism. I see the novel’s satirical edge, conveyed through what Adam Roberts has described as its “fortissimo pastiche,” as a tool, not an ends: Spinrad wants us to introspect, not just point and laugh. For me part of Spinrad’s purpose here must be hermeneutical: The Iron Dream is an attempt to understand and interpret storytelling mythologies — in particular, SF tropes — by turning them back on themselves. The reason these proto-fascist elements exist in our fiction, Spinrad seems to be reminding us, is that, like it or not, we put them there, and confronting that tell us something important about who we are.

Gavriel D. Rosenfeld, in his book The World Hitler Never Made, provides a close reading of The Iron Dream over the course of six pages, and reminds us that the novel was, de facto, banned in West Germany from 1982 to 1990. Critic Edward James updates the terms of our interpretation by describing the novel as a dissection of “the inherently anti-democratic tendencies of the super-hero,” thereby tracing a continuity between Spinrad’s text and graphic novels such as Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns and Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen. Michael Dirda, in a 2008 review of Roberto Bolano’s Nazi Literature in the Americas, picks up on a reference to Spinrad in Bolano’s book, and mentions Robert E. Howard and Robert A. Heinlein as two of Spinrad’s targets. The novel’s enduring impact and importance are without question, as is perhaps the inherent difficulty of enjoying it emotionally.

We now jump forward about a decade, to The Void Captain’s Tale (1983), a first-person account of the forbidden, alternately destructive and redemptive relationship between a male Captain and the female Pilot whose “psychesomic” orgasms quite literally power the ship’s “Star Drive,” as is customary during the story’s Second Starfaring Age. I note that this is a first-person novel because Spinrad uses our immersion in the Captain’s consciousness to great world-building effect; since the Captain thinks and writes in a “sprach” that combines English with Spanish, French, German and Japanese, our experience of his world is filtered by the same language as his is. By using an invented argot, then, Spinrad requires of us that we step beyond our everyday linguistic landscape so we can get closer to the novel’s native world. Our lack of familiarity with their expressions and phrases mimics the sort of cognitive estrangement we would experience if we were suddenly dropped into the middle of the Captain’s culture. In this way, by making his fictional Universe less instantly graspable, Spinrad makes it more credible.

The device is a risky one — applied clumsily, we might end up myopically focused on the cuteness of certain turns of phrase at the expense of other narrative elements —, but I think Spinrad handles it with skill. Gerald Jonas wrote in The New York Times that, “as with all artifice, The Void Captain’s Tale depends on the cooperation of the audience for its effects.” Quite so. I find something freeing and exuberant about The Void Captain’s Tale opening pages, in which our introduction to an interstellar culture is directly contained in that culture’s use of words. A clear example of this is Captain Genro Kane Gupta’s indulgence in the custom of “pedigree and freenom” tale-telling, which not only furnishes us with necessary biographical information about our protagonist, but also clues us in to the idea of “freenoms” and instantly tells us something about the values of the Captain’s culture (the crew of his ship, the Dragon Zephyr, prize telling stories). Soon after this bit of background material, the Captain has his first encounter with Pilot Dominique Alia Wu and, for the next five pages, we switch to her first-person narration, before returning to his for the rest of the novel. Again, this is a bold technical move; by heightening our empathy for Dominique, we are beginning to follow the same illicit path that Genro is following when he gives human dimension and character specificity to his Pilot, who, social protocols dictate, should remain anonymous to him.

If Spinrad is wise to the effects he’s using, so is Genro wise to the tradition of doomed relationship he’s engaging in. At one point, he even asks Dominique if she is the equivalent of a femme fatale. He anticipates the tragic dimension of his chronicle by advancing the novel’s entire plot, with its unresolved ending, in four short paragraphs on page two. It’s not about what happens, we realize at that moment, but how it happens. Genro wants us to understand the innermost workings of his psyche, and in so doing “touch the spirit.” The more we delve into his perceptions and subjective experiences, the better we can appreciate the depth and uncommon self-awareness with which Spinrad has molded him. By the novel’s end, it is impossible to pass judgment on his actions, though they undeniably cause him and his crew great distress. And yet I wouldn’t want the reader to think the entire novel is nothing but a plodding apologia written in a made-up language by a navel-gazing Captain. On the contrary, because Genro’s world is one almost exclusively dedicated to art, eroticism and philosophy, the novel becomes a fascinating excursion into otherworldly customs, theories of perception and belief, and rituals of kinship. Thomas M. Disch saw this work as a high point in Spinrad’s post-Iron Dream career: “The Void Captain’s Tale represents a new synthesis of Spinrad’s main strengths. The earnestness of the metasexual theorizer is qualified by the irony and livened by the playfulness that characterizes The Iron Dream and his best short fiction.”

We should perhaps spend a few more moments on the novel’s engagement with sex. As mentioned earlier, the Pilot’s orgasm, one of such intensity it physically consumes the Pilot and reduces her life expectancy to an average of ten years, is an integral component of the Ship’s technology; without it there would be no Jump and hence no FTL travel. In addition to this, we’re presented with a rich panoply of recreational sex, which functions both as social lubricant and status indicator. Gerald Jonas wrote that Spinrad was “one of a handful of science fiction writers who regularly consider the impact of new technology on the arts,” and in this novel sex is that art. It acts as a distraction from the Void (the theme of travelers between the stars having to cope with boredom is one of Spinrad’s oldest, appearing as far back as his second published story, “Subjectivity,” in 1964). But if sex is an evasion here, it is also a rich form of communication, a reaching inward towards communion. Gone are all the four-letter words and staccato thought-bursts of Bug Jack Barron; here the descriptions are comprised of long, winding sentences replete with “tantric dyadic asanas,” “kundalinic energies,” “erect lingams,” and so on. In this novel Spinrad’s previous deliberate vulgarity has been replaced with sophistication, crassness giving way to a refinement of social intercourse that necessitates pages of the Captain’s description to do it justice. Problematic, though, as some reviewers have noted, is the exclusive focus on heterosexuality; not because we demand political diversity from fiction, but because the kind of classicism that Spinrad otherwise evokes suggests a less restrictive, more open-minded approach to his subject matter, easily attuned, say, to ancient Greek sexual practices. The sustained effect of Spinrad’s invented argot and the baroqueness of his culture border on the delirious, at times tipping over into philosophical-sounding smut and smutty-sounding philosophy. Indeed, the words “esthetics,” “phenomenological,” and “transcend” occur with dizzying regularity. Baird Searles, reviewing the novel in Asimov’s, complained about the repetitiveness of certain words: “I personally came close to feeling that I would throw the book across the room the next time I hit the word ‘thespic’ no matter how appropriate it was to most of the circumstances it described.” In spite of this, he concluded, by gently mocking Spinrad’s style, that the novel is “a frissonic, libidinal tour de force.”

So why, I think it’s legitimate to ask, does Spinrad place such emphasis on sex? One might infer that Spinrad is simply reminding us of the notion of spaceship as phallic symbol. Michael Levy, in The Routledge Companion to Science Fiction, implies as much when he says that the novel “uses Freudian psychology, explicit sexual content, and witty prose to reexamine many of the basic tropes of sf.” But I’d like to focus on the orgasm-as-star-drive conceit. In the novel’s specific setup, it is the Captain, always male, who invariably enters the command to “Jump!”, and thus imposes his masculine will on the Pilot, who is always female. In a very real sense, then, he controls the femininity at the ship’s core. Is this a stand-in for rape? That reading seems at odds with the novel’s elegant tone and discursive asides. As if that weren’t enough, the Captain himself wonders about the rape analogy (!), and discusses it with Dominique, who assures him (and us) that neither of them are truly in control.

I’d like to posit an explanation different from the rape scenario. As Elisabeth Lloyd argues in The Case of the Female Orgasm: Bias in the Science of Evolution (2006), none of the twenty or so long-standing theories that attempt to explain the female orgasm as an adaptive, survival-enhancing trait stand up to thorough scrutiny. Instead, Lloyd proposes an accidental “byproduct” account of the female orgasm in terms of a response to the evolutionarily-driven evolution of the male orgasm. In a way this explanation mirrors that for the existence of male nipples — which confer no obvious survival advantage to males — as a byproduct of female nipples. With this in mind, I’d suggest that Spinrad’s female orgasm is both a statement of what was, before Lloyd’s extensive research, a bit of a conundrum, and the author’s uniquely SF-nal response to it. The Pilot’s orgasm fulfills the function of unknowability, and serves as a kind of transcendence by proxy. It is the Captain’s obsessive wish to understand and experience it for himself that lead him to ruin.

One of the two protagonists of the last novel we’re going to discuss, the near-future Deus X (1992), begins at precisely the opposite side of Captain Genro Kane Gupta: Father Pierre de Leone, nearing the end of his life, only desires to be left alone. The Void Captain is willing to sacrifice himself and everyone else in order to resolve a metaphysical unknown: what will happen with the Ship “blind Jumps”? Will it escape ordinary reality? The great unknown in Father Pierre de Leone’s fictional universe is this: what happens to a human soul when the person’s consciousness is replicated in the vast, non-corporeal cyber-land known as the Big Board? Is the “meatware successor entity” soul-less, or has the soul perhaps been cast into an electronic version of hell? Father Pierre’s faith leads him to believe it’s the former, and he therefore has no wish to investigate the matter. But he becomes a peon in the Church’s ploy to regain its popularity, in a time of crisis and ubiquitous consciousness replication, by providing definitive, empirically-based answers to questions over which it claims authority. Father Pierre therefore ends up in much the same place as the Void Captain. The novel’s other protagonist is Marley Philippe, a black boat captain with a penchant for spliffs and hacking, who’s hired to locate Father Pierre in the Big Board after the theologian has been downloaded into it and kidnapped by mysterious virtual entities claiming to belong to “the Vortex.”

The short novel is told in alternating first-person chapters (in a neat typographical layout, roman numerals are used for Father Pierre’s sections and ordinary numbers for Marley’s). As with The Void Captain’s Tale, the first-person allows for quick immersion. The pacing is brisk, and accelerates frantically during the final pages. Despite the occasional point-of-view observation that strains credulity (as when Marley recalls a “pop cult” from the late twentieth century called “Cyberpunk”), each of the character’s voices is distinct and enjoyable, if at times close to stereotype. Whereas in his earlier works Spinrad conveyed internal anguish in characters whose external settings were often decadently abundant, the present novel’s setting during the Earth’s lean “last days” lends an atmosphere of quiet beauty and reflection, and gives Marley a modicum of peace, or perhaps resignation. Once again, the plot, as writer Gordon Sellar points out in a blog post http://www.gordsellar.com/2011/09/23/deus-x-by-norman-spinrad/, “isn’t really where the book’s charm lies,” but rather “in the way the story is told.” For me part of the book’s unique spell is also derived from the metaphysical questions it poses: its playfulness regarding reverse Turing tests, ontological regressions, and so on. More importantly, I appreciate its overt inclusion of a Catholic viewpoint, rare in mainstream SF. Father Pierre de Leone’s outspokenness and strong views remind me a little of Father Ramon Ruiz-Sanchez in James Blish’s A Case of Conscience (1958).

Deus X, which sees the future Catholic Church led by a woman Pope, adroitly balances opposing forces: faith and atheism, principles and pragmatism, self-repression and self-expression. But in the end, as Gabriel McKee concludes in The Gospel According to Science Fiction, the book is “optimistic about the possibilities of AI and consciousness-modeling, proposing that a machine-copied mind can be as fully real as an organic, human one,” a similar position to the one backed by Robert J. Sawyer’s Mindscan.

Despite what I feel is a pat ending, I find the economy of prose and the richness of ideas amply rewarding, and this is without a doubt one of my favorite Spinrad stories. Gerald Jonas’ comment that “the author has got hold of a powerful metaphor for transcendence that he intends to push to the limit — with thought-provoking results” seems a fair assessment. Other critics, particularly within the field, have expressed less enthusiasm. Gary K. Wolfe, for example, notes that while “Spinrad has set up a genuinely provocative situation, I’m not sure he’s done himself a favor by trying to resolve it in such a conveniently SF-nal manner.” I would argue the exact opposite, that anything but a SF-nal resolution (albeit one less “easy” than the one Spinrad presents) would be cheating. John Clute’s main concern is with the way Spinrad depicts the Church: “It is very difficult to swallow a Christian Church relevantly concerned with the kind of issue at stake here; and it is impossible to imagine one so internally transfigured by humility and good sense that its representatives could begin to admit to Spinrad’s whole litany of sins.” I don’t think the latter directly hinges on the former, and Spinrad’s case for declining membership as a motivating political force suffices within the spare world he’s created. Returning to Spinrad’s ideas about what constitutes SF, here is a clear instance indeed of minds being entirely contingent upon the technological medium with which they’re interacting or, in this case, in which they’re residing. Deus X, viewed this way, is arguably the most purely SF-nal of Spinrad’s novels.

A brief concluding thought on accolades. As the The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction summarizes, Spinrad “won the Prix Utopia in 2003, a life achievement award given by the Utopiales International Festival in Nantes, France; he won no significant awards in America or the UK.” While it’s true that his work has never reached the critical thresholds of popularity or fellow peer support needed to earn these awards, we should remember that he has been nominated for six Hugo awards and six Nebula awards across categories that include dramatic presentation, novel, novella, novelette and nonfiction book. Perhaps my favorite of Spinrad’s short stories is “Carcinoma Angels,” which first appeared in Harlan Ellison’s Dangerous Visions, and which tells the story of Harrison Wintergreen, a prodigy who can seemingly accomplish anything he sets out to, except taking pleasure in his own accomplishments — with tragic results. That story is a compelling reminder to enjoy what we do have while it lasts. Spinrad’s body of fiction, which I’ve only sampled, contains much work whose raison d’etre at first blush appears to be purely confrontational. His non-fiction, which could be the subject of its own essay, can be just as incendiary and intellectually unruly. And he has a tendency to repeat certain phrases — “molecule and charge,” for example, in The Void Captain’s Tale, or “bits and bytes” in Deus X — to a desensitizing degree. Despite this, and the fact that his experiments have not always succeeded as art, commerce, or either, he has nonetheless continued to experiment time and again. That should be regarded as its own accomplishment.