Midwest Book Review

By Diane Simmons

January 2011

Volume 11, Number 1

Harry Hudson, the hero of Michael Harris’s The Chieu Hoi Saloon, reminds me of other hulkingly desperate, endlessly searching, secretly intellectual loners of literature. I think especially Thomas Wolfe’s Eugene Gant, hurling himself into “immense and swarming” New York City. Perhaps it is only the outsider, the tortured seeker for something that couldn’t be found in his nowhere home town, who can truly plumb a great city’s depths.

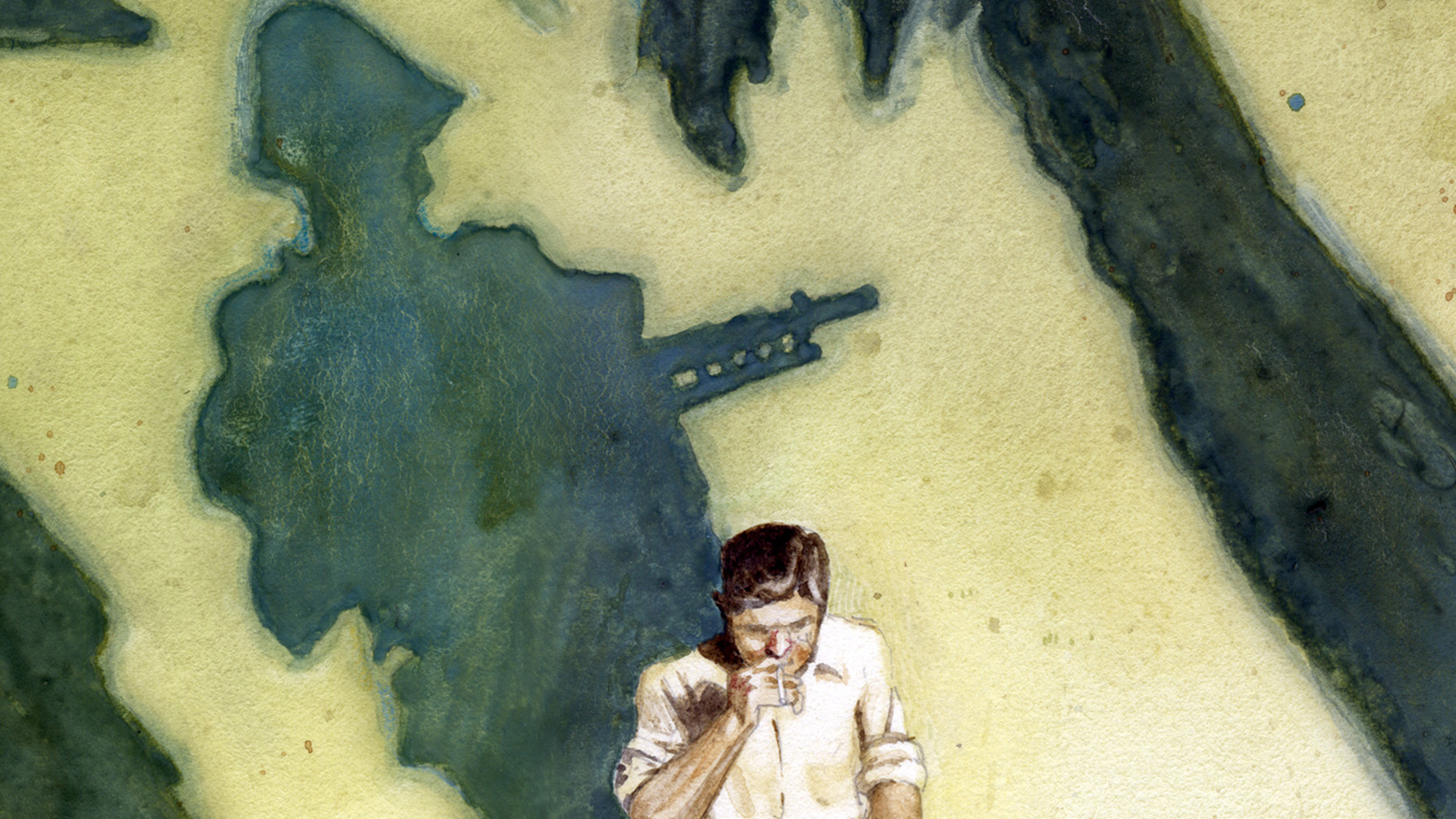

In The Chieu Hoi Saloon, a huge book in which literary meets noir, it’s 1980s Los Angeles, a city festering for the eruption that will follow the Rodney King verdict. Harry Hudson, who has fled/deserted a small town up in Oregon, a failed marriage and a little son, stutters so badly that he can barely talk to anyone but himself. His copy-desk job in a dying newspaper world leaves him plenty of time to shadow box with his past, to re-live the moment when, in a young man’s “drowsiness and fear,” he killed a harmless old Vietnamese, and the even longer moment, fifteen years later, when he was too drunk to fish his little daughter out of the deep end of the swimming pool. With these memories before him, he knows he “has no right ever to feel good again.”

Los Angles, as seen here, seems to be a good place to have come if you are looking to run but have no real hope of hiding. Harry Hudson – as he’s always called – seeks to find himself, or lose himself, in one dive after another, joints where signs such as “SWINGERS WELCOME” and “ONE AT A TIME ONLY IN THE TOILET” tell you all you need to know. Part-time hookers on their way down are willing to love Harry Hudson a little, accept his money and his support, and he at times he becomes so involved with their lives that the book sometimes begins to speak, successfully I think, in their voices, opening up a second window onto the life of the city.

Does our hero find redemption? Let me not say.

But there is one oasis of hope in the book, the Chieu Hoi (exact translation, I think, to sicken and die) run by a woman called Mama Thuy. Her life has been tough too; a young girl during the Vietnam War, she also left behind a son to make her escape. Still she remains whole: beautiful, tough, decent, courageous. The disreputable crew of saloon regulars – those who have long since “lost the ability to control their behavior well enough to pass for normal citizens” — are all in love with her, would lay down their lives for her in a minute.

The Chieu Hoi, though it’s called a saloon, is really, Harry Hudson, knows a church, a “congregation of fools, of incomplete people gathering around Mama Thuy in hope that, somehow, in this one place, some wholeness might “rub off.”