By Charlie Allison

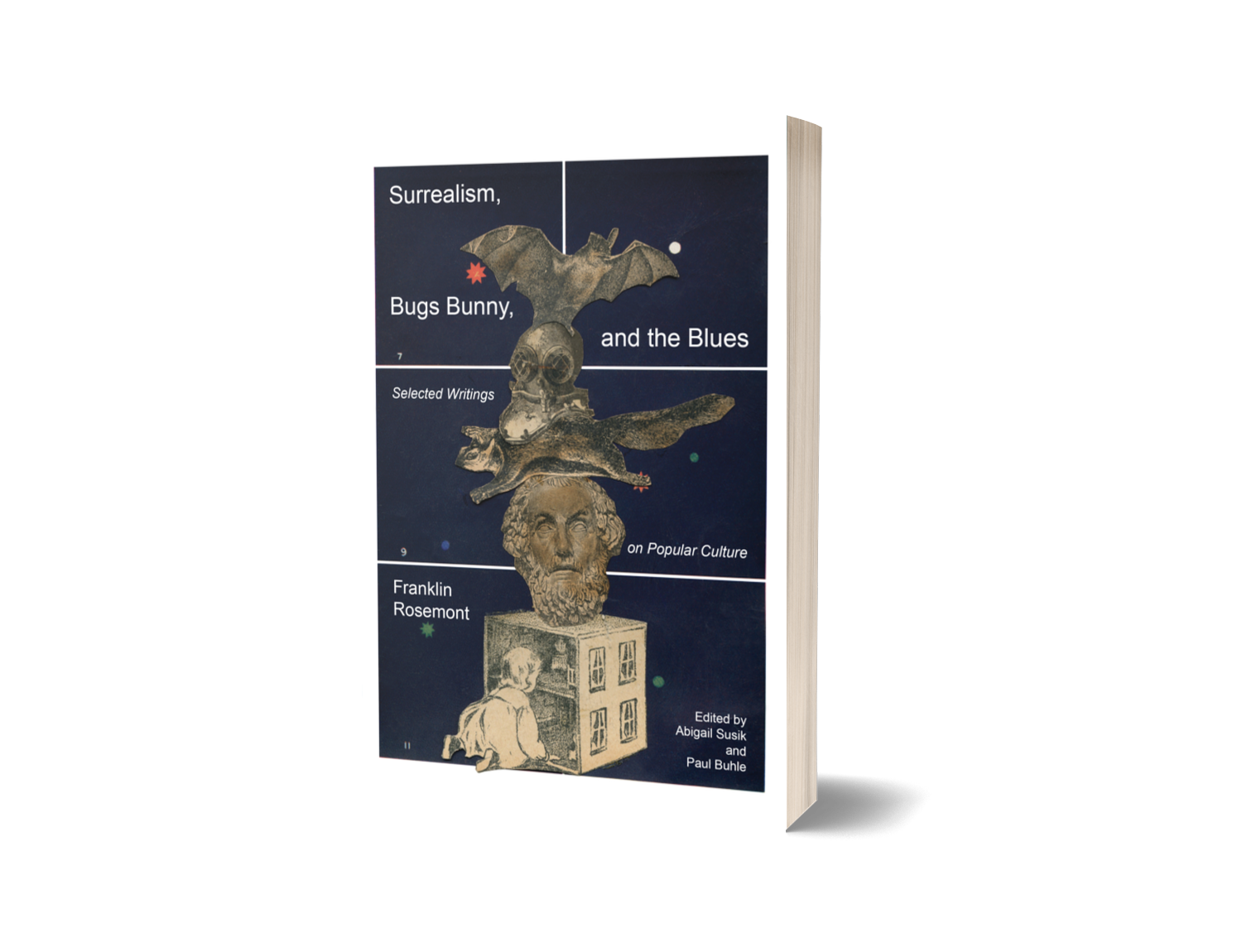

I expected great things when I opened Surrealism, Bugs Bunny and the Blues, PM Press’s collection of the writings of anarchist, artist and surrealist Franklin Rosemont (1943-2009). I didn’t expect to laugh half as much as I did (this is the most fun I’ve had reading a book from PM Press since the marvelous Karl Marx: Private Eye by the redoubtable Jim Feast).

I very much enjoyed PM Press’s wonderful collection of this incorrigible artist’s essays. Masterfully edited, they are supplemented by extremely helpful essays that place Rosemont in his milieu and historical context by Abigail Susik and Paul Buhle. Rosemont declares that the best model for revolutionaries is none other than Bugs Bunny: “… one can scarcely imagine a better model to offer our children than this bold creature who, with his four rabbit’s feet, is the good luck charm of total revolt.”

For Rosemont, Bugs Bunny is the exemplar of all things anti-authoritarian, spontaneous, joyous, and uncontrollable—Bugs Bunny is a revolutionary by temperament and by choice. This is a stark contrast to Chuck Jones’s (the director of several of the best known Bugs Bunny shorts) famous quip: “Bugs Bunny is who we wish we were, Daffy [Duck] is who we are.”

Indeed, Bugs Bunny is a recurring character in Rosemont’s essays. In the wonderfully brief and scalpel-sharp essay “Bugs Bunny and Dialectics” (what a title), Rosemont accurately diagnoses the nature of our current oppressors (true in 1976 and even truer today), writing:

It is impossible to appreciate the genius of the world’s greatest rabbit without understanding Fudd: this bald-headed, slow-witted, hot-tempered, timid, petit bourgeois dwarf with a speech defect, whose principal activity is the defense of his private property. Fudd is the perfect characterization of a specifically modern type: the petty bureaucrat, the authoritarian mediocrity, nephew or grandson of Pa Ubu. If the Ubus (Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin) dominated the period between the two wars, for the last thirty years it is has been the Fudds who have directed our misery: Fudds and more Fudds in the White House, Fudds on the Central Committees of the so-called Communist parties; all the popes have been Fudds; the best selling novelists are all Fudds; Louis Aragorn and Salvador Dali, beginning as anti-Fudds, degenerated into two of the worst of all possible Fudds. Almost alone against them all, Bugs Bunny stands as a veritable symbol of irreducible recalcitrance.

The general spirit of that quote I think is very relevant to today, though I must indulge in a small tangent. The ableist language in the above quote that has not aged well in the fifty plus years since it was written (‘dwarf’, etc.), which is itself a good reminder that Looney Toons themselves were used in places to encourage racial stereotypes and further US war propaganda—making Bugs Bunny the only cartoon character I know of that impersonated as both Hideki Tojo and Josef Stalin—while being casually racist. But I digress: Bugs Bunny is better than a few cringe cartoons made in the nineteen forties.

I feel obliged to continue with Rosemont’s premise and to update it to the modern day: it is hard to imagine a single member of the political/oligarchical class who does not match Rosemont’s descriptor of Fudd in some way. The Democratic Party’s Fudd-like, neoliberal insistence on knee-knocking caution or collaboration in the face of the final fascist takeover of the American state, while trying to avoid upsetting their own deep-pocketed sponsors evinces Fudd at his most befuddled and uncomprehending. The Republican-Trumpist’s self-defeating cruelty for the sake of sport and sadism has more than a shade of resemblance to Fudd running down an ascending escalator, or emptying a rifle into a harmless rabbit’s home for ‘sport.’

Your manager at work is likely a Fudd, as are most CEOs by temperament and social pressure to say nothing of cops, mayors, presidents of all sorts, prison guards, parking enforcement personnel, anyone employed by the TSA, FBI, CIA, ICE, etc. And so on and so forth. This is the world, nay, the planet of Fudds—Rosemont’s presumable nightmare—ever in need of Bugs Bunnies to appear from our holes in the ground and begin setting things right, one exploding cigar, bear trap, backfiring firearm, painted tunnel on wall, and wisecrack at a time.

Rosemont’s affinity for Bugs Bunny also plays into his analysis of what is required for a successful revolution—to Rosemont, humor is not just an accident or frippery. This is in stark contrast to the party line of any given Maoist/Stalinist/Leninist/Trotskyist party, where humor is broadly treated in the same way that Lenin sneeringly described free speech as a “bourgeois affectation.” To counter this assumption that the revolution must be serious and important, Rosemont points out in “Humor: Here Today and Everywhere Tomorrow” that:

attempts to achieve the same [revolutionary] ends by ‘serious’ rational means invariably prove self-defeating. Rational argument affects only a very small number of people a very small part of the time; if this were not the case, the world revolution would have been made long ago, and we would all right now be enjoying life in marvelous anarchy… humor… also provides, in self-defense, weapons of eros-affirmative action. In the world as it is today, humor has become a matter of life and death.

Humor is a potent form of communication and a binding agent against the ruling classes of the globe in Rosemont’s vision—a non-negotiable for the next revolution, rather than an after-thought or a ticket to the gulag. It is tempting to read in that essay from the nineteen eighties, an anticipation of the internet 1.0 and 2.0. That same internet, I would point out, is one of the keys to Bugs Bunny’s longevity and relevance in popular culture in the present day.

Rosemont’s essays are compulsively readable. Indeed, in writing this review it is difficult not to simply copy and paste vast swathes of his writing so he can speak for himself. He has a breezy, personal writing style that flows conversationally, as if he and the reader were simply having an informal chat on interesting topics. He writes as movingly about the role of dance in culture as he does about T-Bone Slim or the surrealist era of early global cinema, citing Les Vampires in particular, to give but a few examples of how far abroad his interests lay. Reading Rosemont is like walking down a deer trail in the forest—you may not know exactly where it’s going, but you’re rather interested to find out—making this a perfect book for travel.

But don’t think that Franklin Rosemont is just good for a belly laugh. Surrealism, Bugs Bunny and the Blues also (among other things) delves into the history of radical environmental movements and their intersections with left politics (including his own beloved IWW) in 20th century America.

As a result, much history that might have been forgotten is placed directly in the hands of the reader, like this notable excerpt from “Radical Environmentalism”:

For several years the daring exploits of a Chicago-area masked man known only as the Fox repeatedly made headlines nationwide, as when he invaded the executive headquarters of US Steel and poured on the office rug buckets of the same dangerous chemical waste the corporation was dumping into Lake Michigan.

Chicago is another prominent thread that runs through this collection of essays. Rosemont writes: “Chicago is the lever that stands San Francisco on its head; it is the dialectical hammer and veritable pulse of all the American dreams.” A full seventh of the book is dedicated to “Chicagoans” and captures the ghost of that city before the neoliberal capitalism of the 1980s stripped away much of what made it worthwhile through further gentrification and the spasmodic expansion of the carceral state.

The role of art in the revolution is treated in Rosemont’s writing as no less indispensable than a theory of revolution or willingness to put one’s body on the line. Hence, his exhaustive essay “History of IWW Cartoons” and long chronicles of Chicago as a hotbed of radical organizing. Rosemont also wrote brief eulogies of notable figures in those movements from the 20th century, including of course, Mel Blanc —the voice of Bugs Bunny.

So it is with profound enjoyment that I end this review with a line that I hope would have done Franklin Rosemont proud and suggest that we meet our cloddish foes with the time honored, drawling battle cry of true revolutionaries: “Nyeaah, what’s up, Doc?”