By Ryan D. Purcell

H-socialisms

“We make graphic art for the people that are fighting. For those people who are asleep, we want to give them purpose—a desire to struggle and to take off their chains of exploitation” (p. 97). Graffiti is the Rorshach inkblot of contemporary street art. It can be vandalism, public art, or activism, depending on the viewer—even all at once. Curiously situated between the public and private spheres of society, most often in city streets, it is a contentious art form that has come to the forefront of social discourse in recent years.

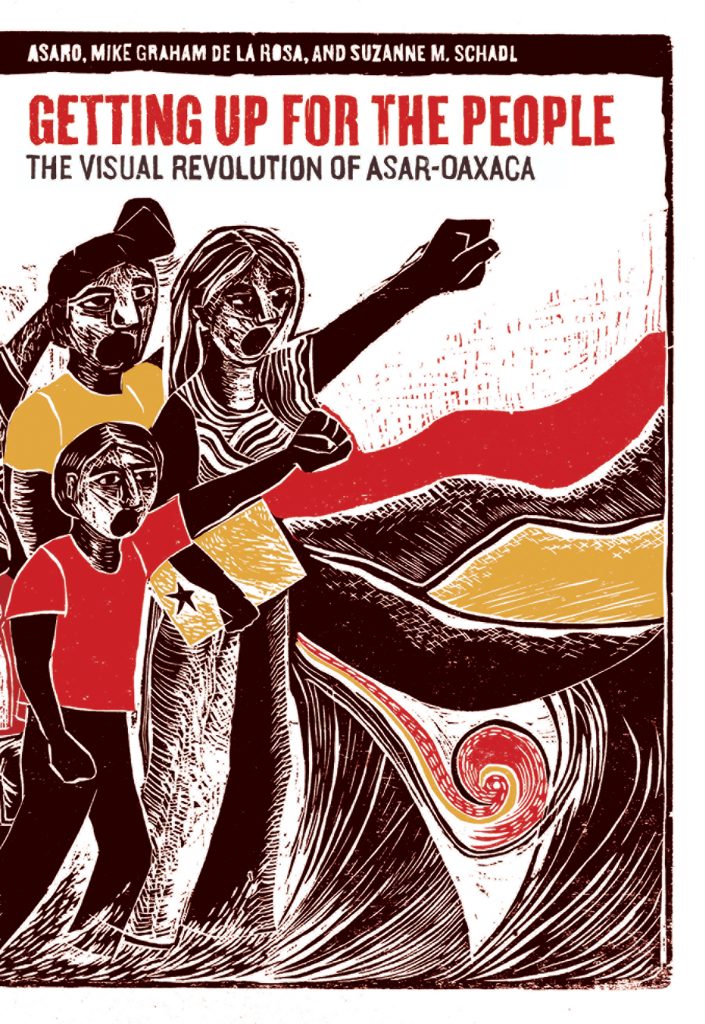

The Assembly of Revolutionary Artists of Oaxaca (ASARO) created a strong visual component during the 2006 social upheaval aimed against the Mexican government. Tags and wheat paste posters that littered Oaxacan streets now hang in academic art museums and in galleries in the United States; yet the images and works of art remain divorced, for the most part, from their original political meaning. From the political context of their origins, however, we can see the wider historic significance of political graffiti from Oaxaca. This, too, is the intent of Getting Up for the People: The Visual Revolution of ASAR-OAXACA.

For twenty-five consecutive years, from 1981 to 2006, teachers from across the southern Mexican region of Oaxaca gathered each May in Ciudad de Juaréz to protest poor living conditions, dismal salaries, and inadequate supplies in Oaxacan schools.[1] The protests generally lasted one to two weeks, often resulting in a small raise for the teachers. But 2006 was different. Oaxaca was one of the poorest states of Mexico, where 80.3 percent of the population lacked sanitation services, street lighting, piped water, and paved streets. Eight out of ten citizens lived in extreme poverty, and the area was rife for rebellion.[2] Social unrest peaked that summer, at the height of a contentious gubernatorial election. The clamor of pots and pans that teachers clapped as protest in Zócalo, the historic city center green, was audible from the statehouse four blocks away. Governor Ulises Ruiz Ortiz, infamous for his long record of political corruption, was willing to comply with their demands as he had the year before, yet the teachers refused to meet with him and insisted on meeting with representatives of the federal government instead. Tensions escalated between protesters encamped in Zócalo and the Oaxacan police until June 14 when Ortiz ordered three thousand police to remove the protest encampment from the square, firing rubber bullets and teargas into the crowd of nonviolent protesters and dispersing the group. Ninety-two teachers were hospitalized; four were killed.[3]

Following the brutal repression of the teachers’ protest, more than three hundred cooperatives, unions, and nongovernment political organizations mobilized and formed the Assamblea Popular del Pueblo de Oaxaca (Popular Assembly of the People of Oaxaca, APPO). This broad-based protest group resumed the occupation of the city square and demanded the resignation of Governor Ortiz: “no leader is going to solve our problems,” the mob chanted behind barricades that they constructed to thwart police.[4] Through the summer and fall, APPO occupied public buildings and seized control of radio stations. After Governor Ortiz fled the state for Mexico City, the revolutionary groups declared themselves the governing body of Oaxaca. The formation of APPO would not have been possible, however, without the help of a special ancillary contingent of political street artists.

Alongside APPO, the Assembly of Revolutionary Artists of Oaxaca (ASARO) formed as a cultural response to the repression of the May protests. Like APPO, ASARO was comprised of many different groups and individuals—graffiti crews, independent graffiti taggers, students, folk artists, and formally trained artists—brought together by their collective rejection of government corruption and widespread poverty. But whereas APPO seized buildings and battled police, ASARO used public art as a weapon against the state.[5] “Our mission is to take our artistic expression to the streets,” reads the ASARO manifesto, “to popular spaces to raise consciousness about the social reality of the modern form of oppression that our people face.”[6] Their posters and graffiti tags, imbued with political slogans and symbols, encouraged the larger protests in Oaxaca by eliciting an aggressive dialogue about the standard of living for many Oaxacans and the failure of the government to provide for its people. Wheat paste posters, graffiti murals, and slogans sprayed in the street galvanized protesters en masse, proving a formidable force against police clad in riot gear. Graffiti disrupts our “normative itinerary,” according to art critic and curator Ivan Arenas; graffiti produces what Walter Benjamin called a kind of shock, Arenas reminds us, or what the Situationalist International framed as détournement, which is a spatial, temporal, political, and playful deviation from a common course, especially in cities.[7] ASARO street art thus encouraged protest in Oaxaca by its very presence. The content of the art was overtly political and in direct opposition to Governor Ortiz’s administration.

ASARO follows a long tradition in Mexico of public art as political statement; the romantic and social realistic murals of David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco, and Diego Rivera celebrating manual labor and the urban proletariat are constant points of reference for the Oaxacan street artists. Other sources of inspiration include the Oaxacan brothers Richard Flores, Enrique, and Jesús Mangón, whose prerevolutionary anarchist newspaper Regeneración openly criticized the corruption and repressive measures of Mexican president Porfirio Díaz during the 1920s (p. 10). Slogans like “All the Power to the People. Neighbors on our feet to fight!” and “End Fascism in Mexico!”; as well as stenciled portraits of Governor Ortiz labeled “Cynic, Thief, Autocrat, Repressor, Murderer” harken back to these socialist forefathers, resurrecting communistic ideology and imagery that includes the iconic visage of Vladimir Lenin and hammer and sickle graffiti prints. “For me, it was essential to communicate with society, the marginalized, who are our neighbors, who we pass every day in the street—the humble working people, not the rich,” explained an anonymous ASARO artist. “The rich exploit the people, but it’s the humble people that make things happen. I think that’s what pueblo is” (p. viii). In all, their art demanded equal rights for disenfranchised groups like agrarian workers, indigenous peoples, and women, all the while critiquing and exposing the hypocrisy of the ruling elite and the brutality of the police, then recently evidenced in the repression of the teachers’ protest.[8]

The street artists targeted public buildings in the historic center of the city, where monuments stood as testaments to years of oppression and exploitation of the peasantry living in the “periferia,” shantytowns along the outer edge of the city. They aimed at the industrial infrastructure, too. Oaxaca, rich in minerals and oil, had been systematically colonized by transnational corporations with the help of state and federal governments.

Revenues from these natural resources reliably bypassed local public coffers, lining the pockets of government officials on their way out of the country. The local peasantry and the small middle class were left bereft of social services like adequate plumbing, housing, and transportation, not to mention education and healthcare. “The earth belongs to those who work it” was a common slogan scrawled in the streets during the 2006 protests which expressed the disdain for the private appropriation of public property and funds. ASARO was a visual assault on the state, adjunct to the APPO.

For a full understanding of the 2006 uprising, Teaching Rebellion: Stories from the Grassroots Mobilization in Oaxaca (2008), edited by Diana Denham and the C.A.S.A. Collective, is essential reading. Replete with firsthand accounts and analyses of the protests, the text brings the reader within earshot of the protesters, their personal struggles, and challenges leading up to the formation of APPO days after the May protests. It includes a survey of Oaxacan street art as a response to police repression, though hardly comprehensive. Louis E. V. Navaer’s account in Protest Graffiti Mexico: Oaxaca (2009), however, tackles political graffiti head on, claiming that whereas graffiti is recognized as public art in most countries, in Oaxaca graffiti doubles as a means to achieve social justice. Perhaps more riveting than the scholarly opinions in Protest Graffiti Mexico, though, are Elaine Sendyk’s photographs, which capture the power of graffiti in Cuidad de Juarez. Her collection of photographs is rare and eyeopening: stenciled graffiti marks that depict empowerment and oppression simultaneously, fittingly engrained in the rough stucco of Oaxacan city walls. The Oaxacan uprising is strikingly visceral through these photos despite the absence of guns and crowds that are surely just beyond the camera frame. Sendyk’s photos make clear that graffiti was as much part of the protests as the demonstrations or riots.

Getting Up for the People: The Visual Revolution of ASAR-Oaxaca takes Navaer’s focus on ASARO graffiti inward with close analyses of the artists and their practices. Coauthored by Mike Graham De La Rosa, an ASARO street artist and scholar of Latin American studies, and Suzanne M. Schadl, curator of Latin American collections at the University of New Mexico, where she teaches Latin American studies, this book’s primacy makes it pertinent among a growing body of scholarship on the 2006 Oaxacan uprising and the role of graffiti in political protest.

Getting Up for the People is a companion to Getting Up Pa’l Pueblo: Tagging ASAR OAXACA, Prints and Stencils, a 2014 exhibition of ASARO art on view at the National Hispanic Cultural Center (NHCC) in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and curated by the authors. De La Rosa and Schadl spotlight the works with brief, though sufficient, descriptions of the historical context. “‘Getting up’ is slang for Guerrilla Artists manifesting images repeatedly in hard to access places,” Schadl explains, “however, ‘getting up’ is about more than being seen; it also requires communications between pueblos or peoples.”[9] And that is the book’s thesis: graffiti in Oaxaca fostered a dialogue between artists and the public, and among the public; it was the glue that held the disparate elements of the APPO together, propelling the protests and enhancing political consciousness. “Images are applied in the streets, inviting people to communicate with them—sometimes by adding a visual twist, or by taking a second glance. Responses can be good or bad; what is important is that they elicit an active dialogue” (p. vii). Communication is not a byproduct of ASARO graffiti, but rather the primary objective. The ASARO collective wrote a manifesto when it formed in 2006, detailing its agenda deploying graffiti teams throughout Oaxaca: “the assembly of revolutionary artists arises from the need to reject and transcend forms of governance and institutional culture and societal structure which have been characterized as discriminatory and dehumanizing for seeking to impose a single version of reality and morality or simulacrum.” They strove for a new social consciousness amid a truly countercultural movement, declaring that political art as communication was key, opening the door to new possibilities for culture and society: “we believe that artistic expression needs to be a form of communication that allows dialogue with all sectors of society and enables the display of real existing conditions, rules, and contradictions of the society we inhabit” (p. 69).

Through close readings of the graffiti tags, juxtaposed with quotes from the ASARO manifesto, De La Rosa and Schadl demonstrate that Oaxacan political street art is more than a revolutionary chronicle. It is a social-psychological testament to the oppression of Latin American people, historically by their governments through the evolution of transnational capitalism. Among other quips, the political graffiti critiqued the extraction of oil and minerals from Oaxacan land, which are exported by the Mexican government at an exorbitant profit and without benefit to the Oaxacan people. One block-print poster features a barefoot peasant tilling the land,”The earth belongs to those who work it” (p. 35 ); another depicts Uncle Sam under an eagle drinking from an oil can, kicking miniature figures with guns who represent the Mexican people (p. 39-40). A block print called “Body Parts on a Railroad” depicts train tracks leading to the United States littered with body parts: a leg labeled “Salvador,” a finger labeled “Mexico,” a hand “Honduras,” and a head “Guatemala” (p. 36). Yet another block-print depicts small animals standing at the opening of a sewer drain, like those used by some immigrants to enter the United States, that runs under a border fence replete with armed police and an American flag (p. 37).[10] From the tight and incisive lens of art criticism infused with social analysis, De La Rosa and Schadl argue cogently that the struggle in Oaxaca is a regional struggle in Central America that continues today. The recent immigration crisis of undocumented minors crossing the Mexican-American border is only the latest episode of an even larger humanitarian crisis afflicting Central America. While Getting Up for the People does not document the fate of undocumented immigrants explicitly, it nonetheless illustrates the social response to the corruption and exploitation in Central America that forces immigrants to flee for the U.S. border.

Despite its attributes, Getting Up for the People leaves the academic reader questioning the theoretical basis of graffiti as protest. In particular, what is the relationship between political graffiti and urban space? That is, does the political potency of graffiti rely on the fact that it is produced in the city, where there is a concentration of people? One suspects as much. Urban public spaces like Zócalo, at the center of Cuidad de Juaréz, were the primary forums of dissent for APPO and the ASARO artists; they are central locations, often close to government buildings, where people are free to congregate. And this is especially important for the graffiti artists, whose political protest relies on being seen by the people, “getting up.” The same was true for Egyptian political street artists during the Arab Spring in 2011 and 2012, when graffiti echoed the chants of protesters in Tahrir Square.[11]

Getting Up for the People presents a unique, up-close perspective on ASARO graffiti, though the authors leave the social mechanics of political graffiti as spectacle unexplored. How protesters understand ASARO tags remains for the reader to interpret. How exactly does the graffiti galvanize a protest? Did ASARO produce graffiti in Oaxacan suburbs, or was this an urban phenomenon exclusively? Was there counter-graffiti produced by opposing political groups, or government censorship of the ASARO graffiti? Another intriguing, though unfulfilled, avenue of inquiry introduced in the text is the strong alliance between ASARO artists and the urban proletariat and peasantry in the “periferia,” the shanty towns at the edges of the city (p. 69). As a point of comparison, graffiti artists in New York City during the 1970s and 1980s originated in the South Bronx ghetto precisely as a reaction to urban decay, economic crisis, and the failure of government to provide for its people. Was this the case in Oaxaca?

As one of the first analytic accounts of ASARO in the Oaxacan uprising, Getting Up for the People lays the foundation for future scholars and critics to explore. More questions are yet to be asked. Getting Up for the People breaks open a fertile field for scholars to cultivate theses and cross-cultural comparisons. Taken into account with Teaching Rebellion and Protest Graffiti Mexico, this text constitutes a new basis for understanding the role of public art in political protest in Central America and abroad. Now we must forge the next wave of scholarship combining political and social practice with academic inquiry, pushing the limits of established norms and definitions of graffiti, protest, and cities.

After Governor Ortiz fled the statehouse in the summer of 2006, APPO assumed control of the city, seizing government buildings and instituting a council to delegate laws and carry on municipal proceedings. Meanwhile, the state police continued an aggressive campaign to quell APPO. Civil war ensued in Ciudad de Juaréz through the fall when a conflict between APPO and state police flared into a shootout, killing four protesters, including a U.S. journalist.[12] Subsequently, Mexican President Vincente Fox sent 3,500 federal police and 5,000 army troops to suppress the insurrection. Military helicopters dropped teargas on the the Zócalo commons, the APPO stronghold, while riot squads cleared the streets block by block. Federal police removed the last of APPO from the municipal buildings in January 2007. Governor Ortiz had stepped down from office in November 2006 and was succeeded by Gabino Cué, yet the transnational corporate connections, drug cartels, and political corruption that made Ortiz infamous continue to plague the state.

Since the 2006 uprising, interest in the ASARO collective has percolated in the United States, where exhibits throughout the country continue to show their political posters and graffiti. Most venues, like Getting Up Pa’l Pueblo exhibi, are geared toward an academic audience. Despite the military repression of APPO, ASARO maintains a vital presence in Oaxaca; artist and activists conduct workshops in their gallery space, Espacio Zapata (named after the historic Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata), on subjects ranging from civil disobedience to graffiti and print making.[13] As De La Rosa and Schadl explain, the workshop and gallery space resist “the dominant aesthetic in the state, working to present social and political issues both in Oaxaca and the world” (p. 104). It is supported by grants from the Oaxacan Ministry of Education and Culture, along with proceeds from selling their art—though they now sell more anitcapitalist T-shirts than prints. Whether the recent ascendence of ASARO’s popularity has diluted its integrity as a potent and politically subversive element, though, is up for debate. If one thing is for certain, it is that ASARO has triggered a new wave of protest tactics. Since the 2006 uprising, graffiti has emerged as a critical voice of people around the world from Egyptian political street artists during the Arab Spring to the abundance of Brazilian graffiti decrying the deleterious effects of the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympic games. Graffiti has become an instrument for social change. As an ASARO tag declared: “It’s possible to change this world. You just have to wake up.”[14]

Notes

[1]. Yakira Teitel, “Women in Oaxaca’s Popular Movement,” Solidarity, ATC 127, March-April 2007, http://www.solidarity-us.org/site/node/457.

[2]. Pat Brown, “The Art of Revolution: Social Resistance in Oaxaca, Mexico,” Common Sense 2: A Journal of Progressive Thought, December 2007, http://commonsense2.com/2007/12/art-culture/the-art-of-revolution-social-resistance-in-oax….

[3]. Karen Wentworth, “A View from the Street: Exhibit from the UNM Libraries Collection Features the Assembly of Revolutionary Artists of Oaxaca,” The University of New Mexico Newsroom, February 28, 2014, www.unm.edu.

[4]. “Violence Flares in Oaxaca, Indymedia Reporter Murdered,” Indymedia UK, December 30, 2006, http://www.indymedia.org.uk/en/2006/10/354689.html.

[5]. Gerlaine Kiamco, “Revolutionary Doesn’t Always Mean Armed Struggle: Identity and Art in ASARO,” Collectives of Support, Solidarity and Action, Issue 50, August 2007, http://www.casacollective.org/story/issue-50-august-2007/revolutionary-doesn-t-always-mean….

[6]. “La tinta grita/The Ink Shouts: The Art of Social Resistance in Oaxaca, Mexico,” Fowler Museum at UCLA, 2008, http://www.fowler.ucla.edu/exhibitions/la-tinta-gritathe-ink-shouts-art-social-resistance-….

[7]. Daniel Tucker, “Chicagoaxaca: An Interview with Ivan Arenas,” Bad at Sports: Contemporary Art Talk, March 4, 2014, http://badatsports.com/2014/chicagoaxaca-an-interview-with-ivan-arenas/.

[8]. “ASARO-Asamblea de Artistas Revolucionarios de Oaxaca,” Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, University of Oregon, http://jsma.uoregon.edu/asaro.

[9]. Suzanne Schadl, “Getting Up P’Al Pueblo! Documenting Cross Border Debates through Visual Storytelling,” New Mexico Humanities: Newsletter of the New Mexico Humanities Council, Spring 2014, http://www.nmhum.org/pdfs/Spring2014nmhcnewsletterweb.pdf.

[10]. For more about the graffiti and the immigrant experience, see Ryan Purcell, “Graffiti Describes the Struggle of Immigrants and Undocumented Minors,” Law Street, July 29, 2014, http://lawstreetmedia.com/blogs/political-graffiti/struggle-of-central-american-immigrants….

[11]. Ryan Purcell, “Egyptian Political Artist Ganzeer on Street Art and Political Protest,” Law Street, August 12, 2014, http://lawstreetmedia.com/blogs/political-graffiti/ganzeer-street-art-political-protest/; and Ryan Purcell, “Defining Egyptian Democracy through Graffiti,” Law Street, June 10, 2014, http://lawstreetmedia.com/blogs/political-graffiti/defining-egyptian-democracy-graffiti/.

[12]. ”Violence flares in Oaxaca, Indymedia reporter murdered”; and “Brad Will 1970-2006: Friends Remember Indymedia Journalist and Activist Killed in Oaxaca,” Democracy Now, October 30, 2006, http://www.democracynow.org/2006/10/30/brad_will_1970_2006_friends_remember.

[13]. Kevin McCloskey, “‘Plaza of the Resistance,’ Espacio Zapata and the ASARO Artists,” Common Sense 2: A Journal of Progressive Thought, March 2009, http://commonsense2.com/2009/03/politics-world/oaxaca-update/.

[14]. Daniel Noll and Audrey Scott, “Oaxacan Street Art: A Revolutionary Expression,” The Looptail, February 6, 2014, http://www.gadventures.com/blog/oaxaca-street-art-a-revolutionary-expression/.

Printable Version: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=41981

Citation: Ryan D. Purcell. Review of Mike Graham de la Rosa, Suzanne M. Schadl, Getting Up for the People: The Visual Revolution of ASAR-OAXACA. H-Socialisms, H-Net Reviews. October, 2014. URL: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=41981

Back to ASARO’s Author Page | Back to Suzanne M. Schadl’s Author Page | Back to Mike Graham de La Rosa’s Author Page