By Pik Smeet

The Socialist Party of Great Britain

September 2013

Alternative history

Alternative history is a strange genre. Its central premise, that small changes in history can lead to radically different worlds is somewhat tenuous: Hitler dying as a small child is unlikely to have prevented a Second World War (merely changing the cast and their precise lines, instead). It is, though, fiction, and it provides a useful means of exploring ‘what ifs’, where the route to the alternative history is usually just an excuse to look at a world that might have been or is simply just different from our own. Being able to imagine different societies is a useful skill, in and of itself.

A few are wish fulfilments, and there’s a few too many ‘If the South won the Civil War’ or ‘If the Germans won the Second World War’ and even ‘If the British Empire never fell’. And of course, the less said about Zeppelins, the better.

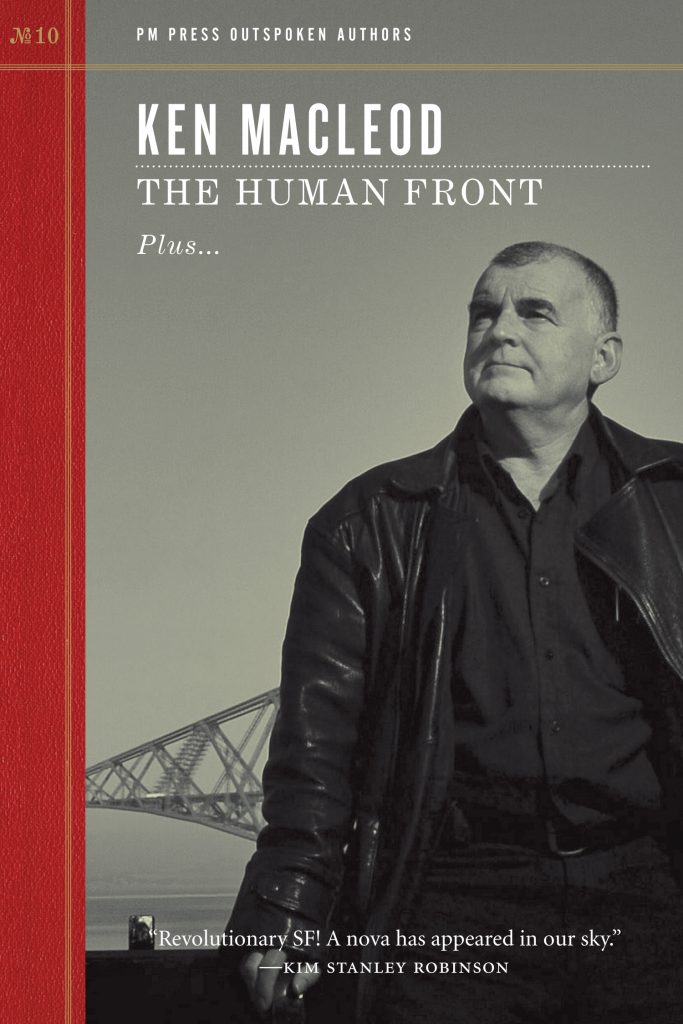

Ken Macleod’s work has featured in our review columns before, often for their interesting examination of the ideas and cultures of the revolutionary left, as well as for his commitment to libertarian (proper sense) causes. The Human Front was his first published novella, and it has recently been reissued, along with an essay and an interview that further flesh out some of its themes.

It begins with the news that the Communist partisan Joseph Stalin has been killed in early 1963. The Soviet Union had fallen in 1949, under assault from Allied super hi-tech secret weapons. As Macleod explains in the essay, this dramatically changes the shape of the post-war world, leading to the unrestrained use of military superiority to maintain the colonial powers’ positions. The absence of the Soviet Union and the ongoing Chinese revolution means Maoism rather than Trotskyism comes to predominate on the British left. This leads to several scenes of ‘People’s War’ in the Scottish Highlands, with all the horror and brutality that entails.

Originally published in 2001, the image of a fugitive Stalin gunned down escaping is now resonant with the fates of Hussein and Bin Laden, and indeed, of our present unipolar world with the unrestrained use of drone strikes. Tens of years on, it seems more like prescience than alternative history. Although the novella soars off into high science fiction for its end twist, its grounding in the Scotland and the Lewis of Macleod’s childhood gives it a sense of solidity, grounding it in real history and left wing arguments remembered.

This reissue is an opportunity to not only consider the themes of the original story, but also alternative history itself and the way in which we shape our pasts to try and make our own future.