By Jeremy Adam Smith

New York Times

July 6th, 2011

Updated July 6, 2011, 06:04 PM

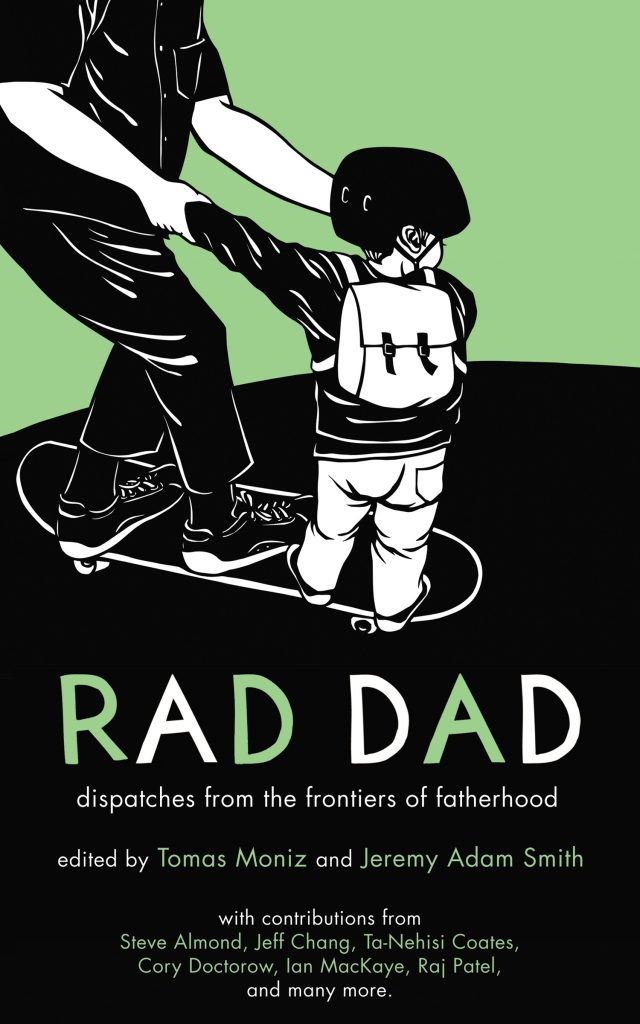

Jeremy Adam Smith is the author of The Daddy Shift, co-editor of the forthcoming anthology Rad Dad: Dispatches from the Frontiers of Fatherhood and a founder of the blog Daddy Dialectic.

Greater gender equality in school and on the job has led to greater equality in housework and childrearing. Today in America, fathers now spend more time with their children and on housework than at any time since researchers started collecting comparable data. I call it “the daddy shift”—the gradual movement away from a definition of fatherhood as pure breadwinning to one that encompasses a capacity of caregiving.

Fathers need to encourage each other to take advantage of leave policies and participate in family life.

Rising inequality and economic instability has meant that families can’t afford specialists anymore. And so they’re moving from a family model that stresses efficiency to one that tries to build resilience in the face of economic shocks. In the ideal resilient family, both women and men are capable of working for pay and working at home.

But families often fall short of this ideal, partially because of lingering structural and interpersonal sexism, and partially because men lack support for their new caregiving roles at both home and work. Studies consistently show that 80 percent to 90 percent of mothers still expect fathers to serve as primary breadwinners (and very few will consider supporting a stay-at-home dad). At work, only 7 percent of American men have access to paid parental leave, among other structural limitations.

How can the daddy shift continue? The to-do list is long. It includes an education campaign to help men of all social classes understand what workplace and public policies can help them be the fathers they want to be—and legal campaigns that will defend their jobs against backward attitudes at work. Men whose mindsets are still shaped by the sole-breadwinner ideal need explicit permission and encouragement from both their female partners and their bosses to take advantage of leave policies and participate in family life.

We also need to shift the language we use to discuss work-family issues in a more inclusive direction, so that it includes fathers as well as mothers. That language should stress resilience and meaning to men instead of the language of equality that has mobilized women. In the end, it’s up to guys to tell the stories of our lives and speak up for what we want. No one will do it for us.

Back to Jeremy Smith’s Author Page | Back to Tomas Moniz’s Author Page