By Brooke Anderson

In These Times

June 16th, 2017

For dads in the crosshairs of systemic oppression, the work of parenting often goes underappreciated.

Every Father’s Day, we’re barraged by commercials encouraging us to show our love for Dad by buying him that shiny new barbecue grill the one with “infrared burners” and “flame-stabilizing grids.”

However, beyond the television advertisements and hallmark cards are real dads just trying to do right by their kids, for whom bathtime and bedtime matter more than beer or barbecues. For many, their parenting often goes unseen, underappreciated or is made more difficult by the system. Among them are teen dads, single papas and houseless fathers. They are fathers grieving children lost to police violence, fathers separated from their kids by border walls or prison cells, and queer, transgender and gender non-conforming parents.

This Father’s Day, meet four all-star dads who’ve gone to exceptional lengths for their kids, parenting from prison cells and homeless shelters, while doing groundbreaking and visionary work in their communities to empower fathers and strengthen families.

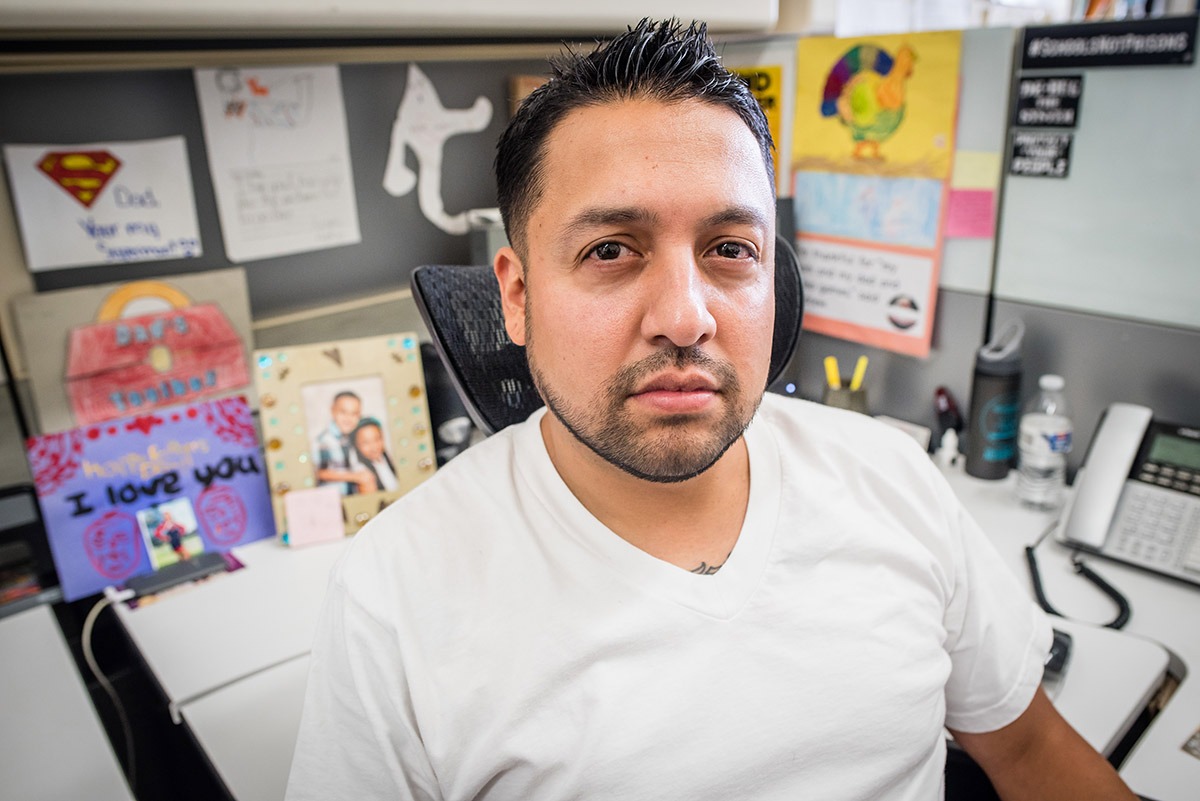

ANDREW LUCERO

Andrew Lucero, a father of two (Haley, 13, and Little Andrew, 10), spent five years of his children’s lives incarcerated. “Inside the system, you parent from a one-hour, once-a-month visit with armed guards who won’t let you hug your kids. Putting the burden on your family to make $20 calls is no joke, so you have to use those wisely,” Lucero recalls. “My son wrote me a letter saying, ‘Dad, I miss you. I went to school today. I played. I made me a sandwich. Dad, I’m sorry. I’ll be a good boy if you come home, Dad.’ It’s hard to read that locked in a cell knowing your son thinks it’s his fault that you’re gone. You want to cook dinner for them, tuck them into bed, take them to school, but you can’t.”

After release, having a felony creates additional barriers to getting a job and accessing food stamps and housing assistance. Lucero says his felony even barred him from going on his kids’ field trips. “We’re not just felons. We’re fathers,” he said. “We’re family members. We’re friends. There’s more to us than this little box.”

Lucero now works at Fathers and Families of San Joaquin (FFSJ) in Stockton, California. FFSJ supports formerly incarcerated adults to rejoin their families and communities. In fact, Lucero was the first person in the county to serve as an AB 109 reentry case manager while still on parole. FFSJ’s Trauma Recovery Program provides clinical services to victims of violence and sexual abuse. Additionally, they run several youth programs and serve two hot meals four days a week to dozens of elders. “We focus on culturally rooted healing,” says Lucero. “We call it cultural cura (culture cures), so we look to our indigenous ways honoring the four directions, sitting in a circle, blowing the horn.”

“Sometimes you don’t feel like Father’s Day is meant for someone who comes from the hood, who’s been in prison. You google “happy families” and it’s folks with picket fences,” says Lucero. “I may not live in a mansion or have a 401(k). I don’t drive a Lexus. My kids ain’t in private school. But I’m prideful that I’m a good father and helping my community.”

PHILLIP STANDING BEAR

Phillip Standing Bear, who grew up on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, is raising six-year-old Cheyanne alone. He says, “She’s the sunshine of my life. She has her struggles, but I love the hell out of her. She doesn’t see evil in the world. She’s different from me; all I’ve seen is evil.”

Being a single father and finding housing on disability hasn’t always been easy. “For a while we went hotel to hotel. Then a church gave us a trailer,” he said. “Now we’re staying with friends, but we’re five people in a one-bedroom house. It’s okay, but she needs her own space.”

Standing Bear is an activist with Poor Magazine, a poor and indigenous peoples-led grassroots media, arts, education and advocacy organization in the Bay Area. “I wrote stories on landlessness and homelessness, because I’ve been through it most of my life. All these parks, golf courses and private properties could be used for housing. During the Super Bowl, if you even looked homeless, the cops arrested you, took your tent. It was tragic. The city could’ve spent the money to build something for the homeless, but they spent it on [wealthier neighborhoods] Yerba Buena, Embarcadero and the Mission.”

“Fathers are important. I never had mine in my life,” he says. “I try my best to make sure she’s happy, well fed, and has somewhere to sleep until I get it all sorted out.”

WILLIE BEAL JR.

Willie Beal Jr. is a father of four whose story of eviction and homelessness is all-too-familiar in the Bay Area: “You be doing all the right things and they still make it hard on you. You’re working, barely getting by, barely able to feed your kids, pay your bills,” he said. “We had a slumlord. There were gas leaks. We complained to codes and compliance but the landlord wouldn’t fix nothing even though we were paying. When we got a little behind on rent, he evicted us.”

Beal’s family was left homeless for two years. He, his mom, his girlfriend and their four kids all lived out of their car while Beal went to work every day. Other times, they stayed in shelters or with friends. The son of legendary Bay Area housing activist Ms. Paula Beal, Willie Beal is no stranger to speaking at city hall or rallies to advocate for his family and others. While homeless, he and his family even occupied the Oakland Mayor’s office to try to get help.

In March, they finally moved into an apartment of their own. Asked what is best about having their own place, Beal says, “This. Just bathtime and these kids bothering me.” Once they get on their feet, Beal says he wants to open a center for families to get help with housing and jobs.

TOMAS MONIZ

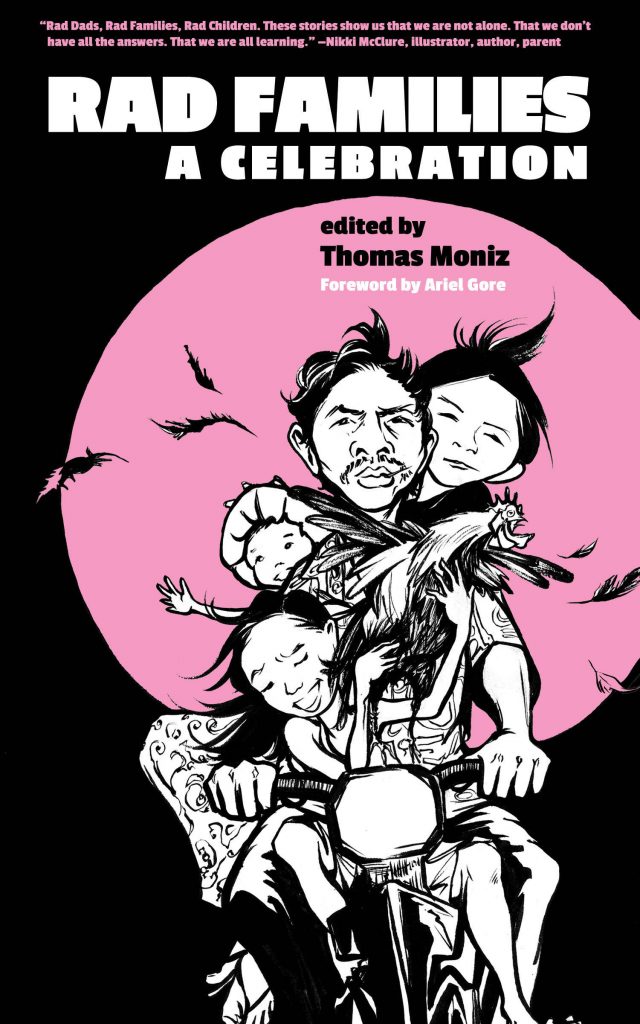

Tomas Moniz is a father of three grown children and author of Rad Dad: Dispatches from the Frontlines of Fatherhood and Rad Families: A Celebration. Moniz had his first child at the age of 20. “It was the greatest dumbest mistake I ever made,” he jokes. “I started Rad Dad when I was looking for community as a father of a teenager who was beginning to push the boundaries on drugs, an instance of porn. I was looking for a different way to parent than the way I was parented by my father, which was very traditional, silent, shaming.”

In Rad Dad, Moniz lifts up the stories of fathers often either demonized or invisibilized by dominant narratives of fatherhood. “The book was originally geared toward male-identified people because it’s important for men to unpack toxic masculinity in the tradition of fathering,” he says. “But two years into the project I realized that the dichotomy of gender was limiting. Queer and trans parents sharing their stories challenged my own relationship to gender, my partner and my children and really broadened the conversation in Rad Dad .”

“Rad Families is more of a celebration,” says Moniz. “I don’t have to prove that there are rad families out there. There are. There have always been amazing people raising and creating families.”

Brooke Anderson is an Oakland, California-based organizer and photojournalist. She has spent 20 years building movements for social, economic, racial and ecological justice. She is a proud union member of the Pacific Media Workers Guild, CWA 39521, AFL-CIO.

Back to Jeremy Smith’s Author Page | Back to Tomas Moniz’s Author Page