by Philip Eil

The Providence Phoenix

November 14, 2012

“THEY SURVEIL. WE HACK.” “THEY BOMB. WE FEED.” “THEY EVICT. WE SHELTER.” “THEY FUCK SHIT UP. WE FIX SHIT UP.”

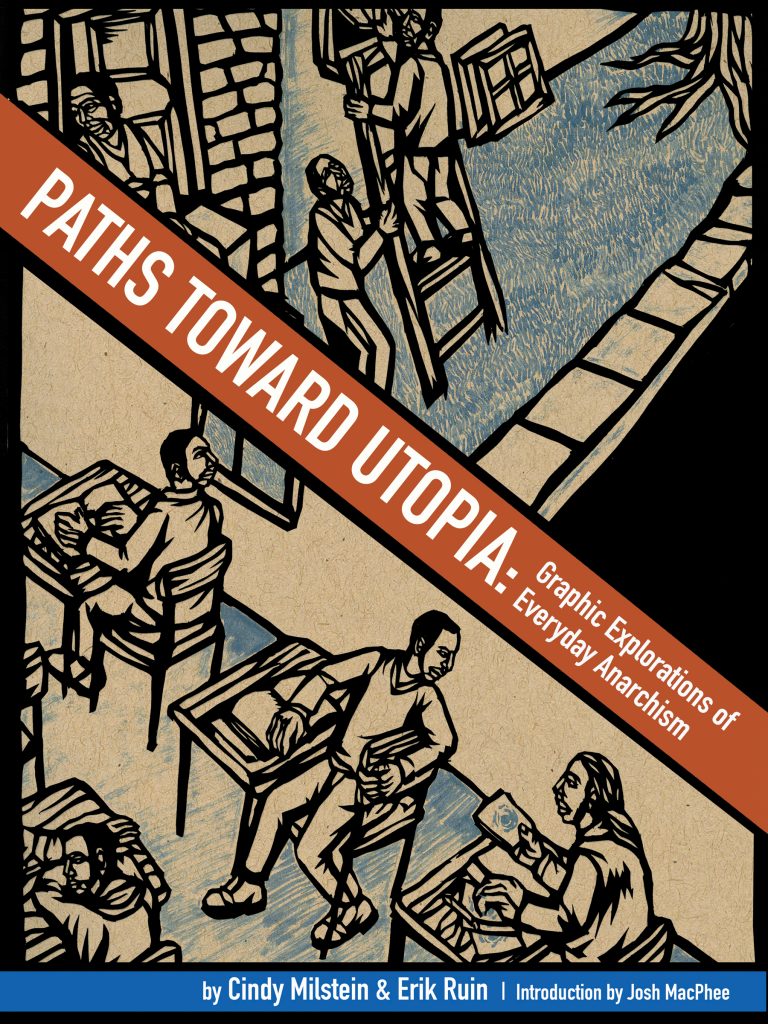

So reads a chapter from the recently released, Paths Toward Utopia: Graphic Explorations of Everyday Anarchism. The words , which hover between poem and essay, are from Cindy Milstein, an author and activist known for her “Anarchism 101” course at the National Conference for Organized Resistance. The images — soup-kettle steam mingling with bomb smoke, protestors stepping in front of bulldozers — are the work of Providence artist Erik Ruin, whom you might recognize from the AS220 Printshop or his projection-screen accompaniment to the city’s Assembly of Light Choir.

Paths is both a nod to the present and past, Milstein explains in her prologue. The book’s title is an homage to the socialist philosopher Martin Buber’s 1944 tract, Paths In Utopia. But the book’s pages, with references to “levees that break in hurricanes & nuclear plants that melt in earthquakes” and “OCCUPY EVERYTHING” banners, are urgently modern. “From Cairo to Madison, from Athens to New York, from Barcelona to Oakland, on the shoulders of Chiapas, Seattle, and Buenos Aires,” Milstein writes, “we the billions have joyfully, startlingly, raced to the window on history that’s been flung open.”

Ruin’s visuals provide a view through this window to a world where bank vaults are re-stocked with seeds and border walls crumble, where crowds flood into libraries and public parks. Many of these images were painstakingly scratched out in a south Providence home studio through a process involving acetate, ink, and X-ACTO blades. I caught up with Ruin in his studio to talk about the book and whether anarchism can lead to utopia, as the title suggests. The interview has been edited and condensed.

IS THERE A DIFFERENCE BETWEEN “ANARCHISM” AND “ANARCHY”? The standard line you’ll hear from a lot of people who consider themselves anarchists — [and] I do consider myself an anarchist — is that anarchy tends to imply, in most people’s minds, chaos or disorder or a lack of order as its primary condition, whereas anarchism tends to be a more systematic approach to the world that resists hierarchy in all of its forms . . . So it’s resistant to government, but not necessarily resistant to order.

CAN YOU TAKE ME THROUGH YOUR VISION OF UTOPIA? No. [Laughs] I mean, I think that’s the definition of “utopia.” It’s “no place.” It’s the thing you’re always moving towards, but never getting. I think that the things that I see as moving there are things that allow people to meet face to face and to have honest discussions about how to move forward as a society, the things that dismantle hierarchical structures of power, particularly structures of abusive power, whether it be racism or gender oppression or capitalism, which is a really big one in our society.

HOW DOES PROVIDENCE STACK UP AS A UTOPIA? IS IT A PLACE WHERE EVERYDAY ANARCHISM IS BEING EXPLORED? I think there is a younger generation of folks, like the Libertalia

folks, who are trying to make things happen in a pretty great way. I support it. I try to come out to things when I can. I do little things for folks here and there, but I don’t feel super plugged in to that. What I feel more plugged into is this sort of DIY arts scene that happens here that I think is a really special place where all these really talented people from really different disciplines and backgrounds and interests, they’re all coming together. I really appreciate how, in form, it’s very experimental. It feels very open in ways that other places don’t.

IS THIS BOOK AN INSTRUCTION MANUAL? What I try to do with images is to form empathic linkages. I’m making this image of this huge crowd of people in Tahrir Square and I’m staring at all these faces for hours and hours as my wrist gradually cramps up and I’m falling in love with these people and I’m deeply engrossed in their lives and feel this deep care for the people I’m depicting in this moment of rebellion.

I’m hoping that that transfers to the viewer and they feel a similar empathy and solidarity with the figures that I depict. I think we live in a very atomized and splintered and alienated and depressing world. And so I’m trying to create these moments, even if it’s a very bleak image, where people are feeling deeply for one another.

I really like [that image] because it gets at, I think, what the core of Tahrir Square was about. It was all of these things happening at the same time. You’ve got your kindergarten. You’ve got your self-organized trash-collection service. And then you have these martyrs’ walls, you have people sleeping on the tanks. And it’s all happening in the same space. There’s all these forms of resistance that are all happening in organic concert with each other. I really like to challenge myself to make things as complex as possible because I think it’s a very complex world and it helps me to understand it — feel at peace with the complexity — when I have this massive, busy image that I’m whittling away at every day.

Back to Cindy Milstein’s Author Page | Back to Erik Ruin’s Author Page