By Ernesto Aguilar

Political Media Review

August 2, 2010

From 1980 to 1992, the Central American country of El Salvador was embroiled in a civil war between the military-led government and the Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional. The United States supported the Salvadoran government under the guise of anti-Communism and, according to many human rights groups, lent aid to paramilitary death squads in the process. Thousands died before officials and guerrillas signed peace accords and the FMLN became a recognized political party. Today, the FMLN has only recently ascended to power.

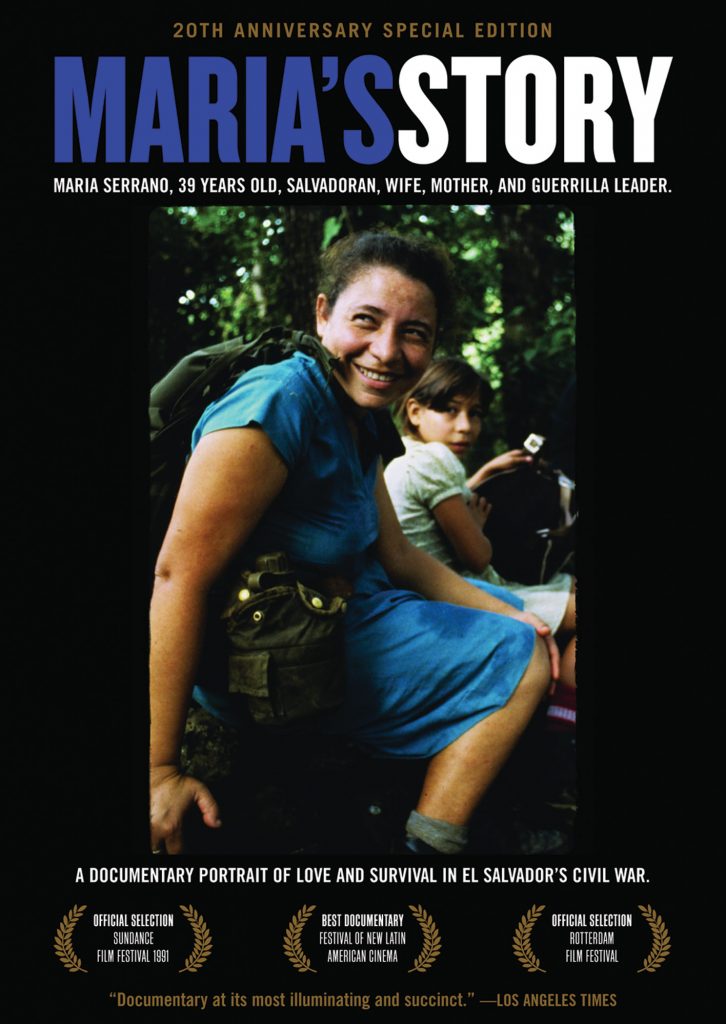

Maria’s Story: A Documentary Portrait Of Love And Survival In El Salvador’s Civil War, a newly reissued DVD of the documentary released some 20 years ago, tells the story of Maria Serrano, an activist and mother engaged in the armed struggle of the period on the side of the FMLN. Serrano, a onetime campesino organizer pushed into the revolution by government repression of the citizenry, gives a very personal account of El Salvador’s fight for resources for the poor. If you told her years ago she would be carrying a gun and leading military operations for the FMLN, Serrano says, she might have thought you crazy. But as the government became more intolerant and violent, hundreds of Salvadorenas and Salvadorenos linked up with revolutionaries in hopes of a better life and an end of measures that strangled with country’s underclass.

Credit is due to the filmmakers for avoiding the dewy romanticism that oftentimes accompanies stories of women, particularly mothers, in political movements. Life is hard in El Salvador’s jungles as seen in Maria’s Story. Serrano sardonically talks about the boots she must wear in spite of holes simply because they cost so much. And she and her children, who are with her in the forests out of necessity based on fears of death squads, treat their lives not as a hero’s journey, but a measure of seeking freedom. As Serrano tells the story, El Salvador’s civil war is not about the government versus socialist insurgents, but about economically disadvantaged people who have nothing fighting because they have everything to gain. Even if the fight means giving every child and every drop of blood, Serrano says, the guerrillas of this moment believe they have no choice but to take up weapons and force a change for the Central American nation’s desperately hungry and destitute people. Serrano warmth and devotion to the cause, in spite of the very real military threats guerillas faced in these days, is nothing less than stunning.

However, Maria’s Story avoids making this a tale of a woman humanizing the revolution through her gender, but of a fighter humanizing the revolution by seeing what poverty and suffering have wrought upon her people. This approach has a variety of effects, but most notably in Maria’s Story, viewers get a glimpse into a movement where gender is a consideration, but clearly so many women are actively involved in the revolution that relegated roles or gendered assumptions are tossed aside, at least in the film. Serrano effectively articulates the objectives of the revolution of the time, and reminds viewers that the guerrillas’ world is hardly glamorous. That larger purpose, she indicates, pushes them forward despite the miseries they face.

Maria’s Story gives a brief update of the protagonists featured in the film, but is fairly thin in terms of extras to the original documentary presented on the DVD. Nevertheless, the documentary is mesmerizing.