By Hal Hinson

The Washington Post

June 28, 1991

In some parts of the globe, walls have come down, wars have been won, but in others, the struggle continues. This is the point that “Maria’s Story” encourages us to remember; it’s lest-we-forget filmmaking.

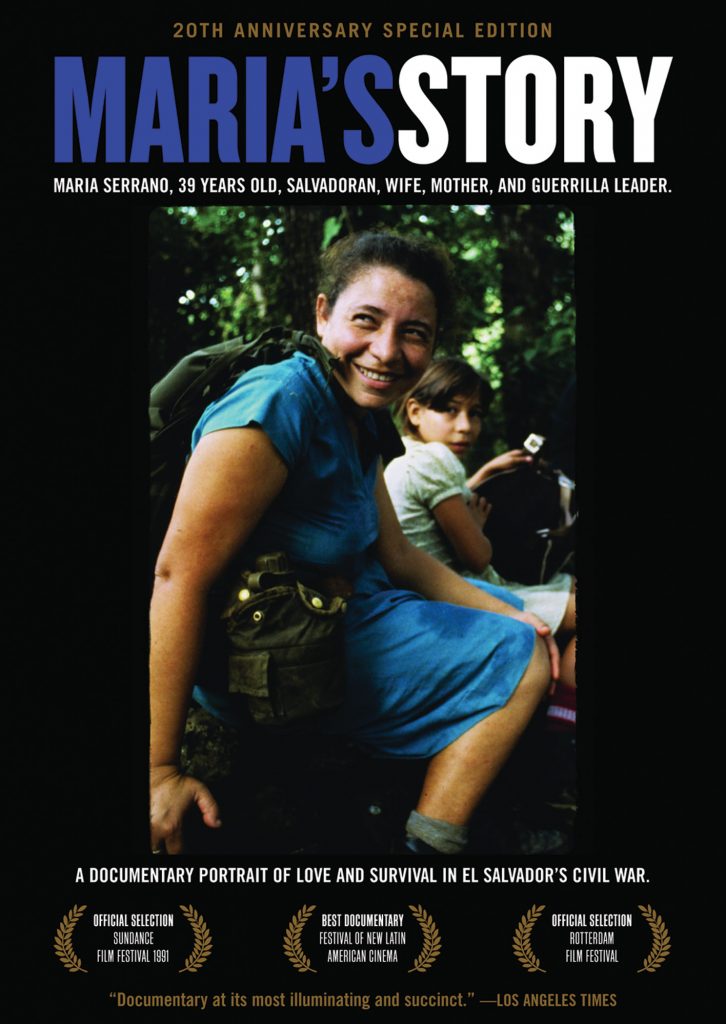

This 53-minute documentary sketches the portrait of Maria Serrano, a 39-year-old peasant turned guerrilla leader who has spent the past 11 years of her life fighting in the hills of El Salvador. Strictly defined, the movie would probably qualify as agitprop; it makes no attempt at a balanced, comprehensive history of that country’s long civil war. Instead, it’s a one-woman’s-eye view of the fight from its ever-shifting front lines.

What we get in “Maria’s Story,” which is partnered on the program at the Biograph with a poetic 28-minute short about freedom of expression titled “Grafitti,” is history in a T-shirt and tattered army boots. The filmmakers follow Maria and her ragtag army of children and old men as they trudge through the hills to their makeshift campsites in preparation for what they hope will be their final offensive against the government. With barely enough money for shoes, much less weapons, this motley assortment is an army in name only; they look as if they couldn’t knock off the lowliest of street gangs, much less a regular combat force.

Still, what these unlikely-looking revolutionaries lack in materials is at least partly made up for in ardor and determination. Everyone must do his part, Maria says, the young, the old, the pretty girls and “the ugly ones, like me.” In the film’s most compelling segment, Maria travels back to her home village, now practically a ghost town because of the long years of fighting, and talks about the events that transformed her from a plain, bookish farm girl into a guerrilla leader, and the story is all the more harrowing for the tone of pragmatic matter-of-factness that marks its teller’s delivery.

The temptation in this variety of political reportage is to pounce on the tragic, and, in the process, reduce it to the sensational. But co-directors Monona Wali and Pamela Cohen never fall into this trap; they refuse to exploit either their subject or their audience. Even when Maria recounts the horror of her young daughter’s mutilation at the hands of government troops, the camera doesn’t swoop in, but remains at a respectful middle distance, as a sober, reverent witness.

In selecting their subject, the filmmakers have chosen shrewdly and brilliantly. Physically, Maria is squat and lumpy, but her sense of mission transforms her, and ambling among the people in one small village, joshing and shaking hands, she becomes a figure of almost mythic potency, a potato-sack Joan of Arc priming her troops for the coming battle. Gradually, the film becomes something more than a document of political struggle; it becomes a movie about rising to the call of greatness.

Maria sees her role as that of midwife to the birth of a new order in her homeland, and, in this regard, her fight transcends the politics of East and West, Marxism and capitalism. This is a war, she says, for food and decent housing and education. What the movie captures here is the drama of self-actualization; it’s a movie about finding your path. Each time that Maria and her husband leave each other to play their different parts in the struggle, they embrace and say goodbye as if it were for the last time. Just before their big offensive, she tells him that she knows she will not live to be an old lady. But he is not to feel sad for her, she says, because she has done exactly what she wanted to do. With this said, she shoulders her weapon and disappears down yet another rocky trail.