Kino-Eye.com

September 20, 2008

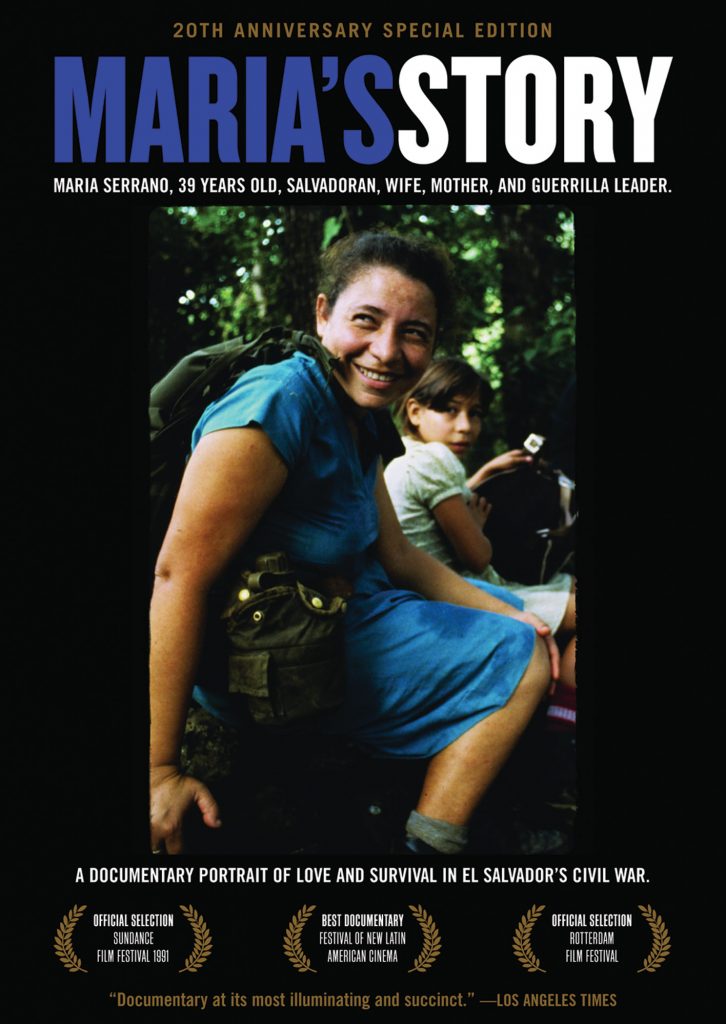

Maria’s Story (1990, Monona Wali & Pamela Cohen, 53 min.) is a documentary portrait of Maria Serrano, a 39-year-old woman who is a peasant, mother, and guerrilla leader who at the time the film was made, had spent over a decade of her life fighting in the hills of El Salvador. Some might condemn the film as agitprop, others would argue it provides an insightful point-of-view of the late-eighties struggle in El Salvador from a highly personal point-of-view. The film is also interesting and important because of the manner in which it was made. More on that later. The film was nominated for the Grand Jury Prize at the 1991 Sundance Film Festival, had a modest theatrical release, and was broadcast by PBS on P.O.V.

I would argue the film is not propaganda due to the fact the filmmakers focused on one woman’s story through which the filmmakers explored the injustice of the situation of El Salvador. Reminds me of the old film school adage, “show don’t tell.” The film was made in conjunction with CISPES (Committee In Solidarity with the People of El Salvador) and was a very effective fundraising tool for them, definitely in part to film’s personal perspective. Viewers might disagree with Maria, her politics, her approach to the problems she faces, but they could not disagree with the reality of her life and the people around her. Not only is there no such thing as objectivity, the duplicitous “objectivity” of the mainstream media stifles real dialog, real debate, real understanding. I like my documentaries with a point-of-view from perspective of real people, and if the filmmaker has an agenda, so be it, as long as they are willing to go to bat for their facts and perspectives and the social reality they are depicting.

But I digress. This post is more about what makes this particular film interesting from the perspective of media technology history: the production of the film was made possible by the use of a new Sony Video8 camcorder that recorded high quality audio and introduced around the time the film started filming. This film was made at a watershed moment in documentary film history. The filmmakers have told the story (ref. Q&A session during a San Francisco screening of the film, circa 1991) of the first time they went down to El Salvador with their 16mm film camera, audio recording gear, and many cans of 16mm film. Maria’s response, in summary, was “with all that gear you can’t move fast, you’re going to get us killed” and the filmmakers returned to San Francisco and had to rethink how they were going to shoot the film.

This was just around the time that Video8 (and soon after Hi8) were being discussed in documentary circles as viable alternatives to 16mm film and Betacam SP for shooting documentary films. There was lots of talk about whether PBS would accept Video8 (and later Hi8) documentaries and the video engineers and film snobs were out in full regalia for this debate. John Knoop, the cinematographer on the project, came up with a solution, using Sony’s new Video8 prosumer camcorder, a small shoulder mounted camera that had high-quality built in audio recording capabilities with real audio meters, and he fashioned some solar panel powered battery chargers for the camera batteries. The prosumer Video8 (and later Hi8) video cameras, were lighter and a tad smaller than most 16mm film cameras like the Aaton LTR popular at the time, but they required more electrical energy than their 16mm counterparts, so a methodology of charging the batteries in the jungle was critical.

With the new smaller gear and a way to charge their batteries far from the power grid, the filmmakers returned to El Salvador and this time Maria allowed them to follow her and her army of children and men as they travel through the hills to their campsites in preparation for what they hope will be their final offensive against the government. With very little resources and a small number of weapons, they are not the revolutionaries we see in movies but this film is about a social reality we often don’t see. Revolutionaries who are also mothers, fathers, sons, daughters, fighting for basic human rights. No stars or effects or steadicam or sweeping crane shots in this film. Just life as the filmmakers observe it day to day living under harsh conditions. The quality of the video image actually works in favor of this film, constantly reminding you this is a mediated experience, not a mimetic virtuality.

The film is also interesting because for the theatrical release the filmmakers had no choice but to produce a film print. This was at the time that a post firm in Los Angeles called Image Transform has perfected a video to film process that was helping filmmakers make film prints that looked good enough to entice some distributors and theaters to program films that had been shot in video. We don’t get hung up on shooting medium these days, but circa 1990 people sure did. The video vs. film as an acquisition medium debate was raging like a California wildfire.

The film is primarily a document of political struggle, but it’s also a turning point technologically because it was among the first films shot in Video8 that presented a compelling and important portrait that could not have been made with the analog photo-chemical film medium. The electronic Video8 format provided for a smaller camera, recording sound and picture in the same camera (16mm required the use of a separate Nagra 1/4″ tape recorder) which further reduced the technological overhead, making this film possible.

The use of a small video camera improves the filmmakers ability to record everyday life in a more intimate fashion. One of the more poignant scenes in the film is when Maria travels back to her home village, devastated by long years of fighting, and talks about the events that transformed her from a young girl into a guerrilla leader, and the story is all the more intense through the unvarnished video image with it’s matter-of-fact starkness, we observe how she’s become a hero to her people, inspiring her troops as they prepare to engage with the government.

There’s another scene I remember in the film when Maria, her soldiers, and the filmmakers are attacked by government troops. The filmmakers dive for cover. The camera, dropped to the ground, continues to record the skirmish, and while the picture from the camera laying on it’s side is not interesting, the soundtrack is about as real as you ca get and brings you there into the moment in a manner that post-production sound effects just can’t do, you know this soundtrack is real, it’s a part of Maria’s life. For this scene, the filmmakers take the actual audio footage of the attack and lay over it images they had shot at a different time. We’re a visual culture and we need images as a frame upon which to experience a film, even though sound carries most of the emotion. Some people complained that it was a re-creation. The documentary purists cried foul. But they did not understand the role of sound in conveying the so-called reality of the moment, and providing authenticity, but that’s a whole other discussion.

At their best, documentary films provide us with points-of-view we could not, or would not (possibly due to ideological bias), ever see on our own. They are extensions of our collective selves that allow us to share social reality with others, and the evolution of cameras from analog film, to analog video, and finally to digital video has made it possible to show so much more, to go places that we could not have gone before. Maria’s Story was made at a very important inflection point in this history, among the first films to show us a social reality we would not have been able to see here in the United States had it not been for the introduction of viable prosumer camcorder with decent image and audio quality from Sony.

I saw the film and heard the filmmakers talk seventeen years ago, so my memory might be sightly inaccurate here and there, but the gist is right. The film is currently distributed by Filmmakers Library and is available on DVD and VHS. A wonderfully effective example of intimate documentary filmmaking and making good use of new technology to produce a story that otherwise could not have been told.