by John L Murphy

Pop Matters

July 1st, 2013

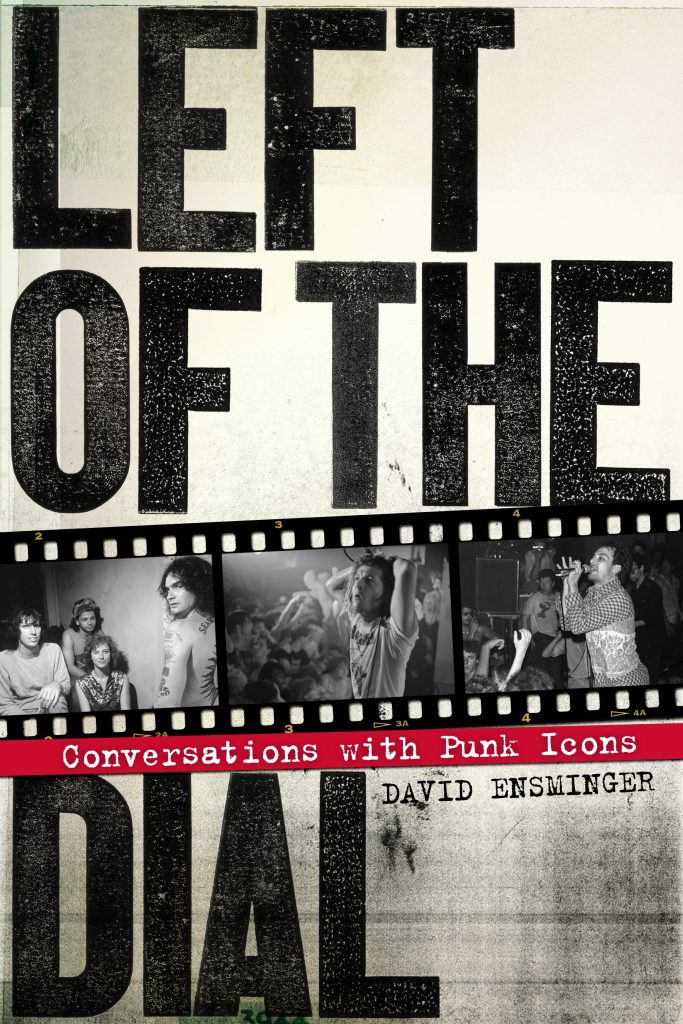

Is Punk Rock Just Urban Folk Music? ‘Left of the Dial‘

Over 20 veterans of the punk scene, over three decades on, tell David Ensminger about their formative years and their chosen values. Fragmented identities, made up on the spot, might define their adolescent musicians for years and bands to come. Some wandered beyond what became the limits of punk and hardcore; others sustain punk’s eclectic, ornery energy. These accounts compile the intellectual and personal transformations attempted by punks from the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, freed of the promotional message “via ratty fanzines” or the dutifully chronological approach of “box store biographies”. As the interviewer sums up his anthology: “These are the words of punk participants centered on the legacy of punk’s sometimes fuzzy political ideology, rupture of cultural norms, media ecology, networking and outreach aims, sexual identity and race relations, and musical nuances.”

Ensminger calls his contributors icons. None matched Joey Ramone’s or Johnny Rotten’s fame, but these clever, driven strategists detoured from the dreary dead end of a decade overwhelmed by Pink Floyd, Yes, and Led Zeppelin, when few up-and-coming bands played their own songs rather than covers by FM-radio monoliths who filled stadiums. Few indie bands, according to some interviewed, even existed (at least on the other side of the garage door); this may smack of hyperbole, but depending on the dismal conditions attested to by many here, it’s the impetus for this “secret history”.

Peter Case, with proto-punks the Nerves, vowed to break out: “We were going to do what the Beatles did, but our strip bar was across the street” in 1974 San Francisco. Ensminger’s focus often settles on California, but given the anglophile emphasis by Jon Savage in his influential account England’s Dreaming, first-person verification from the other side of the world proves necessary. As The Damned’s guitarist Captain Sensible favors, bursting out from the working classes, the band-driven impetus for musical and social change deserves a hearing lately dismissed by elitist trendsetters.

This tilt balances the supposition that American punk rock stayed suburban, middle-class, and white. Chip Kinman of the Dils and later Rank and File brought, as a young bassist, a Communist lyrical stance. He figured this would rouse Golden State audiences to confront their fears better than clichéd swastikas. Similar to Case, Kinman insists on a rootsier, vernacular, populist strain within punk that aligns it to folk, country, and blues music. He argues articulately for the first wave of American punk, arguably predating if not The Ramones than certainly Rotten, as already established by the mid-‘70s in San Francisco and Los Angeles. This oddball, offbeat phase, as L.A.‘s El Vez “the Mexican Elvis” or the denizens of San Francisco’s Deaf Club typify, comprises part one of Left of the Dial. What soon replaced it in tract-home Orange County and the tonier beach cities of the South Bay, hardcore, sounds to Kinman like “machine bands” fixed on an unrelenting discipline and a forceful rigor, exemplified by Black Flag’s SST label in its Henry Rollins phase. As for punk, Kinman labels it the “last white popular music” as he laments its “overdocumented” archival status, and rock’s “self-referential” trap which stymies innovation. No wonder those from the early stages of punk remain true to punk’s unpredictable spirit—by refusing to mimic their own youthful musical molds or models.

Part two, and two-thirds of the book, shoves its way into a mosh pit of “sound and fury”. Mike Palm of O.C.‘s Agent Orange sprinkled surf instrumentals into punk anthems. Suburban surfers elbowed into hardcore’s mosh pits, to push aside the misfits they would have despised a few years earlier in the glitter-glam era when Hollywood and San Francisco punk staggered and flirted amidst gay bars, squatters, and the fringes of the art world such as the Deaf Club.

But subversive or gender-bending punk faded. A uniform of spiked hair, leather jackets, and big boots hobbled purported non-conformists. Representing the transition to the more violent, tribal hardcore O.C. mood of the early ‘80s, Palm praises Rodney Bingenheimer, the KROQ-FM Sunday night d.j. who championed the otherwise impossible to find import vinyl straight out of London, which preceded and then propelled the local L.A. punk scene. (This reviewer also attests to the kindness and generosity which “Rodney on the ROQ” unfailingly showed to his fans—at first very few of us in 1976. His show was our only local lifeline to fresh, startling sounds from abroad or from the late-‘70s underground, before the mass marketing of “alt-rock” by KROQ and imitators.)

The Minutemen’s stalwart bassist Mike Watt entertains with tales of how he and bandmate D. Boon traveled up from San Pedro, 45 minutes south, to Hollywood’s raucous concerts. With a shared love for Creedence Clearwater Revival and Blue Oyster Cult, their terse punk-jazz-folk compressed the idealism of populist punk as it embraced the two teens. Watt affirms: “I’m trying to live up to the personal utopia I felt in my life where I could play anything I want and D. Boon could help me. We don’t have to live up to anything.” Distanced from punk’s bohemian ambiance, but lured in, Watt and Boon settled in to a place (on SST) where CCR and BOC covers coexist with a frenetic, experimental band admiring their peers such as Wire or Richard Hell.

This genial tolerance, as with the plaid shirt sported by Watt in homage to CCR’s John Fogerty, supports Case and Kinman’s confidence (reiterated in typically reliable fashion here by Ian MacKaye of Minor Threat, Fugazi, Dischord Records) that punk’s progressive ethos extends its instigators’ principled, D.I.Y. and anarchic aims. Participants agree that punk unity emerges from its diversity, its ambitions, and its open-mindedness. Watt sums it up: “Back in those days, if you considered yourself punk, you didn’t say ‘I’m punk.’ Now, people say, how are you punk rock? You look like my dad.”

Speaking of punk’s contrasts between participants and stereotypes, part of the fun of this presentation is playing its players off each other. Kinman reserves choice words for Jello Biafra; Biafra lashes out at his former bandmates in the Dead Kennedys. Ensminger holds Shawn Stern (Youth Brigade) to a couple of inconsistencies in his interview, while Kira Roessler (Black Flag) reminds readers of that band’s calculated non-conformity, reacting to the rigid expectations of its own hardcore audience.

Jack Grisham (TSOL) distinguishes the “attitude” of early punk vs. the “music” and the “look” of its later versions, which usually fail to innovate. Embodying the presence of such an innovator, Ensminger introduces Keith Morris (Circle Jerks, Off) via his “extended monologues” during concerts, as “he struts the stage like a well-meaning counselor and history teacher.” As a Texas college instructor and cultural scholar himself (and PopMatters columnist), drummer-editor Ensminger suitably examines the impact of less-heralded figures who continue to strive for experimentation and agitation within the spirit if not always the template of punk.

Apropos, Morris speaks of his affection for his former roommate, the Gun Club’s Jeffrey Lee Pierce. Pierce heaped doses of “aggro” to pepper the Americana musical stew with earthier spices. This pungent blend seeps into an lengthy conversation with Really Red’s U-Ron Bondage. Ensminger as a “digital archivist” may let this meticulous contribution go on much longer than his other entries, but the long career of activist U-Ron, from the mid-‘60s Texas acid-psychedelic era through the Reagan years into Clear Channel and Vans Shoes’ commodification of skate-punk, justifies its inclusion.

Political, sexual, and racial ramifications feature within later chapters. Beefeater’s Fred “Freak” Smith from the D.C. hardcore-funk scene and Article of Faith’s Vic Bondi challenge hardcore dogmatism. Straightedge and indulgent factions contend; Ensminger strives for fairness in hearing out the conflict, if leaning far to the left. He pushes a few interlocutors to clarify or defend their claims. He favors the upstarts (after all, this is published by the anarchist-friendly PM Press) to foment small-scale, non-corporate action to spark wider change. Dave Dictor (MDC) surveys the takeover of the alternative movement by the big labels, and he may champion Obama, but he also hopes that the Greens will—eventually after the Democrats fail—replace the powers that be.

Left of the Dial reminds readers that before Green Day or Rancid, we had Fugazi, MDC, and DOA. The difficulty with this small-scale rebellion endures: how to sustain an audience and make a living from marginal music and radical stances. Many burn out or give in. The little labels themselves encounter difficulties, competing against the majors. Lisa Fancher, founder of Frontier Records who signed many early Southern California bands mentioned here, argues for her side in this complicated situation. Ensminger then appends three “notable persons” to give their testimony. Managers, rights, and royalties, as with any popular music study, play their part in who endures and who succumbs.

There lurk a few slips in transcription (John “Vox” rather than Foxx from Ultravox; “Beechwood” rather than Beachwood for the Hollywood avenue; “Red Cross” or “Kross” for the band who had to respell as “Redd Kross”). Nearly all chapters were previously published; beyond their original readership in fanzines and on Ensminger’s eponymous LotD magazine, some entries needed editorial clarification of band members or fellow musicians casually mentioned only by first or last name by those interviewed.

Minor faults aside, this compendium provides a fitting tribute to punk’s intellectual and political energy, harnessed to a friendlier, if assaultive, approach that invites in all to play and listen. Better yet, it encourages audiences to become activists, to participate for principled change.

It boils down to protest. Thomas Barnett (Strike Anywhere) nods to the Wobblies and Leadbelly. He cites a Flipside fanzine interviewee himself, continuing the chain of credit lengthened in this collection of voices from those who those stand over but not apart from the crowd. “Punk rock is just urban folk music.”