by Blake Underwood

Indypendent Reader

July 15, 2013

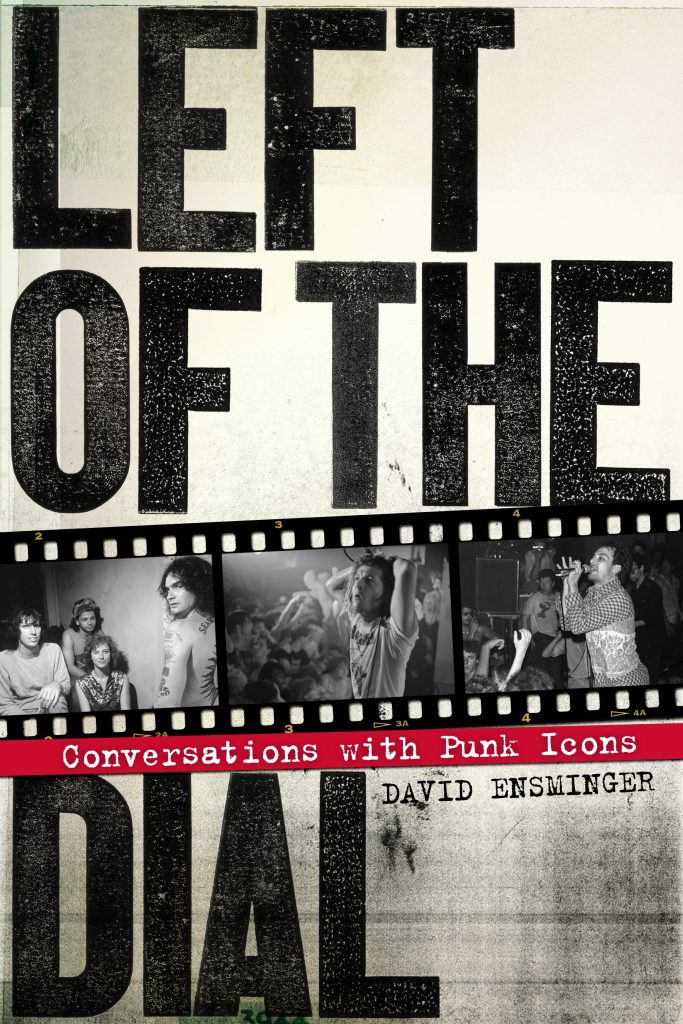

One of the many takeaways from David Ensminger’s newly published Left of the Dial: Conversations with Punk Icons is that subtleties matter. Even the book’s title seems to ask us to examine the distinction between an interview and a conversation, which the author makes clear over and over again. Rather than yet another compilation of call-and-response style interviews, where figures from punk’s history are asked to answer the same context-free questions about why yesterday is more important than today, Ensminger has been able to create real dialogues. The conversations draw out a diverse, narrative history of an all too often essentialized subculture. And while expected names like Ian MacKaye, Jello Biafra, and Keith Morris are present, the list of conversations also includes names that will be much less familiar to many readers, including an “Un-oral” history of San Francisco’s short lived, but historically important show space, The Deaf Club. Each conversation is exceptionally unique, often with a level of specificity that will have readers taking notes to do their own follow-up research, but always providing new insight into the people and topics at each story’s center.

Left of the Dial is broken into two parts. The first, much shorter section, entitled “Tales from the Zero Hour,” provides a rather diverse array of perspectives on the “birth” of punk from its Rock ‘n’ Roll and New Wave parents.Yet, rather than mining tired territory on the hows and whys of punk’s evolution, these accounts go quite far to describe the musical, cultural and, to a lesser degree, political landscapes that existed in the spaces that early punks carved out, often before they even called themselves punks. Featuring, amongst others, Peter Case of the Nerves, Captain Sensible (aka Raymond Burns) of the Damned, and Tony Kinman of the Dils, the conversations cover the influences on early punk music, the almost accidental development of DIY (do-it-yourself) touring, and the first attempts at mainstream cooptation of punk culture. Ensminger’s distinctly personal questions means that the conversations are allowed to meander, creating narratives that are fascinating, yet rather difficult to summarize — such as when Captain Sensible answers a question about the difficulty of international touring in the late 1970s, with a caustic anecdote about Patti Smith and the atmosphere around the infamous CBGB, one of the earliest venues to feature punk bands in New York City. However, where this style would pose difficulty with more narrowly historical documentations, here it shines. From the start, Ensminger treats his readers like adults, either knowledgeable enough to contextualize each divergent thread of conversation, or smart enough to seek and find the materials to do so.

Though heavily focused on bands formed in the late 1970’s through the 1980’s, the book’s second section, “Hardcore Sound and Fury,” attempts to follow punk’s lineage all the way through to the present. Opening with the likes of Mike Palm and Gregg Turner, of Agent Orange and the Angry Samoans respectively, Ensminger begins to unravel the development of hardcore punk, an amorphous term used to describe the more aurally aggressive and politically confrontational subgenre that came to dominate the scene, especially in the mid-to-late 1980s.

The conversations follow the same logic as those in the first section, allowing personal experiences and anecdotes to provide explicit references, but inexplicit answers to the broader, underlying questions that too often lose their power when answered with black and white clarity. A tactic that seems employed by the book as a whole.

For example, like many of its counterparts, Left of the Dial might be criticized for its limited inclusion of women, punks of color, and other marginalized groups whose influence in and on punk has been enormous. But Ensminger attempts to allow these narratives to shine through, while not necessarily highlighting them. To this end, the inclusion of Kira Roessler not only in the book’s contents, but also on its cover, stands out in bold relief. From 1983 to 1985, Roessler played bass in Black Flag, arguably one the most important bands in punk history.

Yet, many of the bands contemporary fans are likely unaware that the band ever featured a female member, much less one who played on the band’s last four LPs. But instead of the political pandering and essentialism that can too often be counted on in such a scenario, Ensminger’s conversation with Roessler is nuanced. Without blunt, tokenizing questions, she is able to speak to the sexism and prejudice that existed towards her while the band was on the road, while never seeming to summarize her role simply as “that girl who was in Black Flag.”

Similarly, Beefeater’s Fred “Freak” Smith briefly discusses his experience as a black punk in a DC scene dominated by white, middle-class men, with a type of candor that few interviewers allow for. And though Ensminger steers Smith in this direction, it is clearly with the intention of creating a round understanding of his subject’s experience, and not to simply check a proverbial box. [Note: For those interested, Ensminger has done extensive documentary work on women and people of color in punk history. See links at the end of this review.]

The loose style of Ensminger’s conversations sometimes leaves the reader wanting to ask their own follow-up questions, perhaps about Tony Kinman’s seeming disdain for Jello Biafra, but one is rarely disappointed with the final product. Occasionally, an elaborated introduction seems called for, especially in the first section of the book where readers may need more background information to contextualize the personalities, but this is not a book aimed at the totally uninitiated. Those without a cursory knowledge of punk history will likely be lost, and those looking for a comprehensive historical document will be disappointed. Yet, the book closes with two interviews that really seem to convey punk’s broad, enduring influence.

Speaking with Dave Dictor of MDC and Thomas Barnett of Strike Anywhere, Ensminger creates a snapshot of punk’s power as a form musical, cultural, and political resistance to the status quo. Both long-time frontmen, Dictor and Barnett have used the stage, literal and figurative, to voice the constant critique that is at the heart of punk, even when that hearis itself the target of their critique.And we are able to find the foundations of these voices, unearthing the varied inspiration these men have found from such sources as Black Power politics, the hippie generation, anarchism, and their punk predecessors.

Because punk continues to maintain an ethic of self-reliance, while also understanding the need for evolution and even reinvention, Ensminger understands that these foundations and their narratives are invaluable. While even some of voices contained within will deny that punk continues to live and endure under new contexts and with new sounds, this book belies that notion. If today’s punks and their music looked and sounded the same as their predecessors, then the reactionary, antagonistic spirit of the culture would be all but lost. The fact that punk spaces continue to serve as sources of political and personal experimentation is a testament to the strength of those foundations. The conversations in Left of the Dial speak to much more than the longevity of a particular sound or style, they speak to the very existence of a culture that has outlived those who declared it dead decades ago. Regardless of how long a record stays on your turntable, if it truly matters, its importance will outlive the ringing in your ears.

References:

http://blackpunkarchive.wordpress.com/

http://punkwomen.wordpress.com/

http://punkandpolitics.wordpress.com/

http://washingtondcpunk.wordpress.com/