Daily life in San Francisco frequently involves bearing witness to yet another suddenly-shuttered local business, mostly the ones that don’t worry so much about their looks, but instead are packed to the brim with everyday things, the urban version of a subsistence economy that’s long fed lives and cultures.

In the Tenderloin, word has it that some new municipal ordinance or regulation (or whim of city officials and police?) requires that everyone be able to see at least four feet into a business through its front windows. The rationale one hears is that corner stores with their mostly covered-over glass are fronts for drug dealing, which is likely true on occasion. Rationales always work that way: an ounce of truth, a pound of fabrication. Drug dealing is, after all, an open secret in the TL. The hidden agenda is creating another mechanism for ousting the struggling low-end businesses that need to fill every inch of their square footage to make a go of it and still serve customers who are no longer welcome in their own neighborhoods in steeply expensive San Francisco.

In the Mission, such unassuming businesses offering still-affordable goods and services include produce stands, dollar stores, dentists, fabric and clothing shops, pharmacies, taquerias, shoe and jewelry repair, church supplies, bodegas, electronics and hardware, laundromats galore, locksmiths, pawnbrokers, utilitarian furniture dealers, donut-and-Chinese-food spots, smoke shops, printers, and the like. They are places where people still know and remember each other, characters and quirks alike, and where proprietors have knowledge of how to fix your wristwatch or what fruit you eat every morning. They are intertwined with other community institutions like public schools, storefront churches, community health clinics, youth and mural arts programs, an indigenous Friendship House, food banks and Food Not Bombs, labor halls, senior centers, and soccer fields. Mostly, they are the places — tangible physical spaces — that reflect as well as reinforce the lifeways of those who call this neighborhood home.

Or used to. Daily, you witness disappearing acts.

You walk by the bedraggled but sweet California Poppy Flower Shop (“the nicest owners ever!”) on 16th Street one day, with its affordable plants spilling out the door on flimsy shelves and milk crates. The very next day, its windows are covered in opaque plastic, haphazardly taped in place. All is gone, save for the bright-orange hand-painted sign — offering floral arrangements and balloons for everything from “funeral” to “party” to “first communion” — still hanging over a mom-and-pop space that is no more.

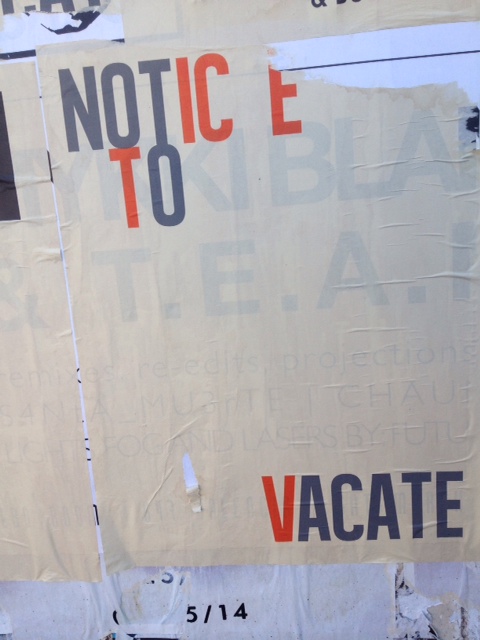

There are many windows such as this. Overnight one can’t see into them at all anymore, not because of abundance, but because of absence. They get covered in brown paper or white plastic. Soon a crisp white-paper building permit will be added, supplying dates and fine print and foreboding.

Overnight, daily, you wake to witness a building whose front is now masked in raw plywood. The next day the now-painted plywood, in smooth-dull blue or gray, boasts “Post no bills,” stenciled in a different paint color, as if trying hard to pass itself off as street art. Actual street art is increasingly buffed over, even those expansive murals, political and/or pretty, that have long been this neighborhood’s signature, or covered by advertising circulars, an unspoken faux pas until now. Graffiti artists vainly try to reclaim turf, even as the walls for such expropriation come tumbling down almost faster than one can shake a can of spray paint.

The following day, a half block of street-level commercial spots with apartments above them is now ringed with scaffolding and decorated with construction netting, ready for preening. You’ve already noticed massive metal cranes hovering high in the distance, helping grow taller buildings, but their flock seems to be multiplying, moving closer. Busy work crews show up the day after that. The music of hammers and saws fills the sun-warmed air. Within what feels like only a week or so, one can start peering through large expanses of new plate glass with “for lease” signs and realtors names affixed to them, into large swaths of clean, white, sanitized space, illuminated by strong-white lights. Clean, new surveillance cameras make eye contact with the fresh drywall and lone modular table covered in blueprints inside this ready-to-go fishbowl of emptiness. Space is at a premium, so nothing remains vacant long. There seems to be no end to high-end restaurants as new eager occupiers.

You wonder why you’re anxious more often.

And even as whole new businesses and entire new buildings pop up like unnatural mushrooms from one day to the next, all of them confidently scaling a higher and higher economic ladder in terms of their price tags, nearly every city block seems vulnerable to a 5-story, 115-unit here or a 10-story, 350-unit glass, steel, and smug redevelopment plan there. Such plans are touted as progress, smiling harbingers of “well-paying” jobs and “affordable” housing. They are hurtled full-speed forward by developers who set up small, unadvertised “community meetings” to offer bribes, or what in polite company they call “benefits.” There, developers offer handshakes to trusting schools and parents, churches and parishioners, nonprofits and community groups, labor unions, bike coalitions, and local merchants to smooth the way for city approval, as if that were ever in doubt. Such crumbs will either get folded into the final sales, so the developers will still get their cake, or more likely forgotten altogether once the demolition ball starts swinging.

And it swings so fast and furious that you don’t even see it coming. Wham! Inexplicably, there’s another vacant lot. Boom! You look at the pristine dirt and scratch your head, since you can’t quite even recall what was there before. This lot, like so many others, has been tidily vanquished, awaiting a structure that bears no family resemblance to this neighborhood. It won’t have to wait long. Oh, and to gently ease your dysphoria, real estate visionaries have also kindly changed the name of your neighborhood to something that raises prices and erases memories.

The same goes for “improvements” to “public” spaces. “What did that small park between 19th and 20th streets on Valencia used to look like? There were big, beautiful shade trees lining the entrance before, right?” Ah, yes! But like the windows of Tenderloin liquor and corner stores, they too had to be opened up for spying-eyes visibility, felled as suspected leafy-green accomplices to alleged wrongdoings such as people of the wrong income bracket or skin color hanging out in a park. Never mind the parklets; those were improved from the get-go. Just a few days ago, you got wind that parklets will soon troop down from Valencia Street (or is it now “Valencia Corridor”?) to Mission Street, in advance, your paranoia whispers, of that thoroughfare being conquered as well.

Running late for your minimum-wage service-sector job or later still for your community college class — that is, while both are still available in the Mission — you get lost along the way. Well-worn landmarks are increasingly rare, and so it’s increasingly difficult to navigate your own neighborhood by familiar, distinctive, humanly scaled signposts. The markers of a lifetime are today’s garbage, already carted away, after carefully being sorted into compostable, recyclable, or landfill. So are the reasons you felt seen and nurtured, even alive, whether around language or food, culture or gender. You’re told that it’s rubbish to resist change. But this isn’t about pennies; there’s a wholesale sellout of your and others’ communities.

A slogan from an earlier era in your neighborhood rings in your ears: “people not profit.” How passé! Today it pays, for instance, to recycle the rainbow that hung over the entryway of Esta Noche, the now-bashed Latino gay bar closed in the blink of an eye on 16th Street, such that in its monotone replacement bar, hetero-gringos can frolic under it in search of additional pots of gold while sipping their artisanal whiskey and talking app start-ups.

You stand witness, hungover from drinking in the sameness that’s leveling your hilly city.

It dawns on you, while staring bleakly at yet another new high rise that you’re pretty sure wasn’t there yesterday, that Malvina Reynolds’s “Little Boxes” song bemoaning 1960s’ Daly City suburban sprawl in the form of middle-class homes of different pastel-bright colors “all made out of ticky-tacky” that “all look just the same” needs rewriting. Out with the old! Peter Seeger, who made this song famous, is dead, and this is 2014s’ San Francisco, not some warm-and-folkie, socially minded place. Now it’s urban “little boxes,” piled upward, one on top of the other, to form big boxes colored in the blah tans and muted grays of neo-uber-upper-class condos that “all look just the same.”

The Mission more than ever is home to an indistinguishable flatness, sterilely prefabricated for a too-heterogeneous group of resettlers: young white males who make over a hundred thousand or far more, and who line up for the private white buses with darkened windows that roam the streets and patronize bright-white stores selling individual pieces of manicured dark chocolate, or the new and newer bars and restaurants with tiny flickering candles and “barn wood” decor that seem to form a seamless line of near-private spaces. It is as if all these people need or maybe even desire is a $10,500-a-month, two-bedroom apartment situated atop growing numbers of look-alike hot spots within which to wine and dine after their fancily paid workday many miles south. And each day, each city block, each person, looks more like the next one — and the next and the next . . .

Vertigo ensues. To recall which street you’re on, or how to find your way home, if you still have one, you’re almost compelled to use the now dog-earred cafes that arose during the last wave of displacements as guideposts. But they are also being demolished.

The joke, it appears, is even on the hipsters who came here in earlier dot-com times. The ironic sensibility that they pioneered has now been enclosed today into things like a sales gallery for the art of selling the “New Mission” in the form of luxury developments such as Vida, Spanish for “life,” but spelling “death” in any language for most residents of what’s left of their community.

For daily life, too, entails being witness to the “clean up” that is going on in the Mission, where police concentrate their work on picking off poor and brown people. The cops, in near 24/7 presence now at places like the 16th Street BART station, can always find some infraction — things that if done by someone else would be ignored. Suddenly, certain faces and bodies get stopped, ticketed, and/or arrested far more frequently for walking, biking, parking, sleeping, sitting, peeing, eating, and socializing in the wrong ways, in the wrong spots, at the wrong time. A fifty-five-year-old lifelong San Franciscan, one of a motley bunch gathering in an equally motley space to organize against the mounting injustices, explains how he is homeless now, yet fastidious about picking up debris from his open-air public housing. “After all, it’s my home!” The police nevertheless woke him and his roofless neighbors one recent morning to say “leave.” “But where am I supposed to go? This city is my home,” he told them, adding, “Is it a crime to be homeless?”

Not only developers, but also “average people” help the police as willing executioners in this North American version of ethnic cleansing. Someone calls 911 on a low- to no-income white woman who hangs out on a public plaza and struggles in general, and the police whisk her off involuntarily to a psyche ward for allegedly acting “erratically.” Another do-gooder on another day calls 911 when they see a working-class brown man taking a break on a city hill overlooking his neighborhood. You remember sitting on that hill many times, sometimes sad, sometimes contemplative, to clear your mind, too. Multiple cops with multiple bullets arrive to gun this young man down. They spend a full day trying to cover their tracks before informing his family, likely failing to mention that it was murder by their fellows in blue.

Other fellow cops, a couple months prior, “swept up” a public space by pushing away a group of black men who’d long used it as their backyard, in a neighborhood where most don’t have such amenities as personal backyards — although you recently heard that a Google (or was it Twitter or Facebook?) higher-up bought a charming Mission Victorian, paid workers to hoist the whole house up one story, and added a swimming pool on the new ground floor. The men were forced from their bustling plaza to a nearby secluded alley for their socializing. Days later, one of them was stabbed to death. The blood on the hands of the police, even if secondary, dried quickly. A week or so later, you walk down the narrow lane, breathing in the smell of urine and rotten vegetables, to pay homage to this latest victim, whose friends have erected a sweet yet pitiful shrine.

One witnesses daily another type of violence, widely enforced: dehumanization.

Its softer, gentler version comes in the form of cell phones and tablets. Daily you lose count of the number of people who bump into your body with theirs, or come too close for comfort to your body with their motorcycle or car, absentminded all. All they see is their rectangular devises. You are just another thing to them, if they notice that much about you. They talk to themselves, even when with their friends, or text during conversations and dates, without listening. No one calls 911 on them to complain of erratic behavior. Yesterday, an acquaintance called your name in friendly hello on the street so you could both then chat amicably, and it struck you as odd, which felt odd in itself.

Mostly, though, all the numerous acts of unkindness that you witness are forms of straight-up ugly, effective dehumanization, which not only hits you as odd but also rips at your own humanity.

In the death camps of Nazi Germany, a derogatory term was developed among inmates for those who had given up on themselves as even being human and therefore were resigned about dying. Or more accurately, didn’t care about life or death because they couldn’t understand themselves as humans anymore. These “Muselmann” were already dead, made so socially, systematically. The process was incremental, meant to chip away little by little, imperceptibly, at various parts of one’s dignity as well as material basis until one was dehumanized, and hence neutralized, almost before one knew it. It was nothing personal; it was a well-oiled machine.

Another mechanism from that distant time was extermination, not simply of peoples, but even the very memory and trace of them. You saw that lack when you visited abandoned forests or fields in Europe, the overgrow remnants of former neighborhoods or maybe a village. Everything became ash: buildings, books, humans, graveyards. Gone as if never there. Who or what is left to complain, much less recall or even miss anything of it? That particular annihilation touched your own peoples’ ghosts, so you wanted to see it, even if it often wasn’t there to see, and that made you even more poignantly aware that many other near-total obliterations have happened — are happening — to other peoples. You wonder if in today’s Mission, dehumanization will look less and less like cultural appropriation, and more akin to cultural erasure.

San Francisco is no fascist state, of course. There’s no need to repeat history, since that could mean conjuring up historic forms of rebellion, too. (Far better to freeze the history of labor uprisings, whether by dockworkers or migrant workers, on aesthetically pleasing plaques as selling points for tourists and techies.) A different system, not yet precisely named by history, is emerging, thanks to the creative class.

Here, cold, hard, driving rain soaks already-grimy sleeping bags and blankets, wilts cardboard, drips through tents barely in one piece, and beneath them all, one can make out skeletal frames, hollow faces, vacant eyes. But most people stop looking at these lumps. Heaps of humans become obstacles to unconsciously step around without a second thought, like avoiding a parking meter or one of those trees set in “Mexican”-themed grates on the sidewalks. It’s a cultivated practice to not pay attention — one you can’t seem to master.

It eats away at you, helplessly, that a mom with preemie and toddlers was evicted from her apartment, then an SRO or two, and then a shelter, which has limited space and time limits. She and her kids — and other Muselwomen and Muselchildren like them — then have to find sidewalks as bedrooms, alleys as bathrooms, dumpsters as kitchens, with each evening’s misty-cold-fog as their wallpaper. (Vans aren’t an option any longer; the city outlawed them from parking overnight, in the knowledge that vehicles have become homes for many. Some friends who were subletting one of these vans got evicted — their third or fourth eviction.) Rumor has it that if this mom and others can hold out long enough for the completion of the “visionary” Transbay Transit Center that’s “transforming downtown,” coincidentally on top of a former homeless encampment, there will be paid workers to greet them at the door, handing one-way bus passes out, like candy.

Others couldn’t wait. You hear of a ninety-four-year-old woman, evicted from her home of many years, who recently found not another house but instead death on streets that weren’t a good shelter. Another woman just celebrated her ninety-eighth birthday in her now near-empty apartment building. All the other tenants, save one friend who has stuck it out with her, took buyouts and left. She and her friend are now a week shy of eviction to who knows where. People die from the heartbreak of displacement, too.

There’s another form of dehumanization going on in your neighborhood, where people ask aloud, “But if I can now sell my house for $5 million, why shouldn’t I be able to?” and then confide in you, only slightly embarrassed, that most homeless people don’t desire homes because they aren’t like us. They are messy, spreading their belongings on the pavement around them. You counter that many people are messy, but it’s hidden within the privacy of their homes, behind windows that you can’t see into. And besides, how is one supposed to be a good housekeeper without a house? You and your new, progressive acquaintance walk gingerly around one of the many mini-encampments, made of blankets and shopping carts and, if you look closely, humans. Your temporary companion mutters, “See, they don’t want homes.”

Another nice-seeming person on another day tells you, “We need police to clean up public spaces because people urinate in them. It’s hard for families to have to smell that.” “What if we added lots of public toilets instead?” “Those types of people would just destroy them. They like peeing outside.”

You feel depression as constant companion, and start to fear going out for fear of all you now witness on a regular basis, for all such conversations with would-be good citizens. So you isolate yourself. You stay home, because for the time being you still have one, and flip through Facebook to relieve your stress.

You read about the how small drones — cute-as-a-button helicoptery things, or maybe they’ll dress them up as pinãtas — will soon be test marketed in your neighborhood, since their creator just moved here and wants to have his fun. These drones will deliver pizzas and aspirin right to your door, and you won’t even have to tip them! In a hop, skip, and jump, perhaps they’ll deliver bullets (out with the real police, in with the robotic ones, which other new neighbor-creators are likely developing).

Another post tells of how the porn company Kink.com is moving out of its castle-like building down the block, and you envision Facebook becoming the next overload-king of that space, constructing moats and installing cannons — just for fun. After all, the Twitter fortress further down the street recently imported and reassembled old log cabins as playful reminders for its employees of earlier gold rush days. You begin to believe in dragons who save you and your neighbors, peasants all, and fantasize about Trojan horses being wheeled up to the mighty stone walls of this former armory.

The next Facebook story reports that the SFPD is on “high alert” and police officers are jittery after the “unease” stoked by their own murder of that young Latino man on the public city hill, and you worry that a dragon or even Trojan horse will be no match.

A text jars you back to reality. It’s from a housemate, explaining that your landlord wants a meeting — the landlord who a few days ago, clambered up to an adjoining flat roof next to your home and banged against your second-story living room window. Your landlord is tightening the screws to softly evict you, thereby avoiding “problems” in their effort to make bank on this building. It’s not just four walls and a rent check; it’s your home, filled with people you’ve come to rely on and love, embedded in a community you’ve come to rely on and love. An acquaintance last week spoke of how his landlord showed up and knocked him to the ground, bruising him; he brought a video camera to their next get-together. Other landlords hire thugs, call in sheriffs. This class war is getting personal!

Personal is slightly preferable; you can reason with a person, maybe change their mind. Or you can use direct “peer” pressure, like in the film Boom, the Sound of Eviction, when during the dot-com displacement in the Mission, kids from a family faced with eviction took their touching hand-painted signs and a “don’t uproot us” potted plant down the street to their landlord’s corner store. They won. A small victory, but each person who can stay in their home and neighborhood is a great victory nonetheless.

Mostly, these days, it’s not personal. This is another aspect of dehumanization here. It’s a high-tech machine. It’s the faceless impersonality of development companies as serial evictors, tiny handfuls (maybe only one handful) of elites who have houses in many cities around the world yet live in a bubble, global investors, a system called capitalism, an institution called racism. It’s also faceless statistics, as dots bleeding into each other on SF maps showing those who’ve been Ellis Acted, or how blacks and Latinos are disproportionately being disappeared. Who is there to talk to directly about these dots? Where do these structures of displacement reside? At the corner store, if it hasn’t yet been replaced by a juice bar, there’s only a poorly paid employee, who soon will be evicted too.

You begin to feel crazy, as if everything and everyone is being banished. The oft-repeated gallows humor circulating that “only ‘the big one’ will save San Francisco, or at least avenge it” repeats in your head like a bad pop song. You eat at your favorite pupuseria way too often out of anguish that it will be gone the next time you head toward its door. You practice every anxiety-reduction method that’s worked for you in the past. Each one only seems to heighten the tension: a walk to the park finds that park torn asunder in some new upscaling project; lap swimming puts you in a locker room where folks chat about millions and billions, as if they are casually speaking about the weather; sitting by the Bay means watching baby-faced techies on their lunch hour engage in trust-building exercises on the grassy embankment.

So you resort to panic-reduction maneuvers that you’ve always been highly skeptical of, such as guided meditation, following the recommendation of your sensitive sliding-scale therapist, who herself doesn’t make enough money to live in the city any longer. The guided meditation actually seems to start working, supplying inklings of “loving kindness” to quell your class rage — a rage that you never felt so deeply before, or in such quantity. Then your guide says that he’s going on a trip and needs to get a substitute for the next few weeks: his amazing friend who teaches mindfulness at Google.

Your vertigo becomes a near-permanent ailment.

A compassionate lawyer at a free legal clinic met with you and one of your many housemates a couple weeks ago, offering sound advice on the next steps in your collective fight to evade eviction. You could feel calm spreading through your body as he spoke, and recognized that sensation as atypical. Calm isn’t something one finds in the Mission much these days. Then your housemate asked, “Our situation is so precarious and uncertain. We’re so anxious. What can we do so it doesn’t feel that way?” With a caring yet serious look, the lawyer replied, “Your situation is precarious and uncertain.”

There are days when you’ve wondered if you have the “right” to fret about staying here. You’ve only lived in this neighborhood five years, or maybe ten or fifteen. Maybe your skin isn’t dark enough, or your first language isn’t Chinese, or this isn’t where you were born, where your grandmother lived and is buried. Perhaps you aren’t a day laborer. Nor are you someone who is disabled, gets by on social security, or has AIDS. Potentially you could find somewhere else to go, even if it has no meaning or you’ll be all alone, unlike those who’ve had a border that crossed them, a husband “back home” who beat them, a family in some small town that abandoned them, their now-trans daughter.

For all the differences among you, it’s clear that “precarious” and “uncertain” are everyone’s devils in your neighborhood now — that is, everyone who doesn’t have control over whether or not they get to stay put in a place that they, in all their varied ways, have made into a home. You, too, have lost other homes, other people, and know how fragile such communal bonds are, precisely because you and so many millions in so many neighborhoods and cities are given no choice, are systematically separated and broken, made to be at the mercy of a powerful sameness — a sameness that only money can buy.

But money is only paper or plastic, not people. You and your many neighbors are different. You are capable of remembering that you are still people, who bleed and suffer. People who care for others who bleed and suffer. You are those who care to alleviate suffering, and hold up life against death, even if it’s a Sisyphean task. Even if you’re told to leave your home in sixty days, or thirty or even three, by someone or something for whom it’s only a shell that makes them that money. Even if you ultimately lose.

This is the secret that’s becoming more visible in your neighborhood. Of late it’s allowed you to remark, with relief, that your failure to ignore all the suffering in plain sight is actually a sign that you’re not lost, and many others aren’t either.

You begin to let yourself overhear random conversations on the street, and the speakers are pleased when you interrupt them to share in their tales of precariousness. Everywhere you go, now that you’ve steeled yourself to listen to uncertainty again, there’s gladly exchanged talk of what many in this neighborhood and city are experiencing, because it feels better to face adversity openly with others.

Ghost stories get told around the flame of destruction. The collective telling turns into the fuel not for the fire that wants to engulf your neighborhood until it’s only ash; it serves as warm-up for resistance, cooking up a banquet of strategies, tactics, and alternatives.

You go to a “march for justice” mourning both death and displacement, and a thousand community members also show up, including a housemate who you’ve never seen join such gatherings. Your housemate mentions how they’ve been feeling depressed, isolating themselves from all the loss going on around us. You trade narratives of this gnawing contingency, and both of you soften a bit at the unburdening. A bit later on that same march, you share a hug — following the empathetic lead of dozens and dozens of others who’ve just done the same — with the grieving father whose son was murdered so recently by police, right atop the mist-covered hill that you’re now all standing on, as pallbearers of memory and regeneration. You’re pretty sure that this outpouring was comfort amid his sorrow.

Daily, before each and every unique place and person in your neighborhood is gone, you try to imprint their images on your mind, as your own sacred Day of Dead memorial. You start to notice that others are doing this as well, ever more boldly. A figure painted into an old mural on a school’s exterior now has a “stop the evictions” placard in their hand; a new mural on the side of another building portrays buses being blocked by strong hands, like the real-life Google and Apple buses that are increasingly getting hindered. A little cardboard graveyard and skeleton are perched atop a 24th Street business, a visible “shame on you” for all that’s being stolen, even as almost weekly now, people gather to do eviction defense with their cardboard signs and still-breathing bodies.

More and more, in the yet-breathing landscape of your neighborhood, there are posters declaring “resist” wheatpasted on walls, art shows and performances revolving around anti-eviction themes, stickers on building sites urging people to “defend the bay,” and banners asserting an “eviction-free SF” and promising that neighbors together will “defend our homes.” These are but the visual post-its, though, for the grounded organizing that’s freely spreading, self-initiated by those targeted for displacement who want to hold fast to this place.

It occurs to you that your weekly calendar has suddenly filled up. There are coalition meetings to stand firm against a proposed luxury development and in favor of neighborhood self-determination, organizing meetings geared toward education and others discussing direct action, informal assemblies to kick off new anti-gentrification projects, a tenants convention to hear about a whole building of renters who said a resounding no to their landlord for a year and won, rallies and marches, a week of coordinated actions, Coffee Not Cops and Potlucks Not Gentrification. You hardly have time to squeeze in reading all the news articles about all sorts of other interventions you didn’t even know were happening. Next week is even busier.

One can do shifts at housing rights offices or hand out tenants’ rights literature on the street, screen-print materials for upcoming protests, join in street theater such as “evict the evictor” office visits, speak out at public hearings, set up a public film screening about Redevelopment in 1970s’ San Francisco, engage in disruption with your affinity group, and the list grows longer. Because at each gathering, more solidarity not charity is forged, more ideas are sparked and put into action. Mostly, you and others are tightening the threads of human(e) interaction that might keep your neighborhood intact.

You don’t like or agree with everyone you meet — and you’re meeting and befriending more and more folks by the day doing this communal organizing — and they don’t all like or agree with you. Yet you notice that people take time for each other now. The varied levels of likes and dislikes, eccentricities and experiences, when learned as well as acknowledged, are exactly the stuff of what makes up an interwoven community. They also remake it. The growing number of people struggling together are, daily, better able to savor interdependence, expanding circles of cooperation. With each meeting or potluck, each direct action or organizing effort, your neighborhood feels more and more like a vibrant community again, a place not completely lost. A place, more to the point, worth saving.

There are, in fact, little wins here and there, maybe because of this. As people get to know each other, you all get better at having each others’ backs, trying out new tactics, and not being as judgmental about others trying stuff out too. If a Google bus gets blocked by fed-up people dancing in clownish spandex outfits or someone vomiting, well, both are good fun — and both are having an impact. You get better at remaining open and not being as depressed. Different types of organizers, with different politics, along with those new to creating waves, are more generous toward each other, more forgiving. Here, among our many differences, people increasingly see each other as equally vulnerable, as people not statistics or categories. They ask each other questions, and listen kindly to each others’ responses. A home is saved here; an apartment complex or social space holds solid there. Or you congregate for another meeting in a space that you’d forgotten was saved the last time around.

Eviction has a face. Many faces. Those faces begin to know each other, and seem to look less stressed. They smile more. You do too. And you recall other moments of loss, and how it made a world of difference whether such grief was grappled with on your own, isolated, or as part of a caring community. When loss happens, because it will, in one form or another, it will be both sadder than ever, since you’ve fallen in love all over again with this neighborhood, and easier, due to these deepened relationships. You know that this is exactly what you all are fighting for, as militia armed with heart and humanity, against a militarized, powerful, heartless, and inhuman foe.

Together, you draw a sharp line in the sand: “We don’t want to go. This is our home.”

You try extra hard to be patient when people who don’t live here say, a bit too mindlessly, “San Francisco is SO over.” Because now, daily, you are witness to all the reasons — people and place — that solidify why this is home. Because it’s not over if it’s your home and, more crucially, a shared home in still so many ways with still so many others who have made home here.

Yes, many have already been displaced and erased from this neighborhood, this city, these lands, in earlier periods, in earlier upheavals. Beneath the chain drugstore and fast-food spot, Chinese grocery, Latino bar, and public transit hub and plaza across the street from you — things useful to people who cling to this neighborhood, yet slated for demo and replacement with million-plus-dollar condos — lies fragments of the first indigenous village and its dead, killed off long before this was even San Francisco. In your neighborhood lie vestiges of other peoples, other cultures, long given the cruel boot.

For those who were able to remain through it all, however, and those who came later and have become part of the fabric of this place — because home and community are all about the varied fabrics of face-to-face interconnections, not seamless surfaces or social mediums — the potential final nail-in-the-coffin of your neighborhood can’t go unchallenged. There’s a larger point to be made, as beacon for other such places across this continent, around the globe, in territories occupied and neighborhoods razed. You and others keenly feel the weight of that responsibility, past and present.

There’s also that smaller, mundane, and perhaps far more important point, and it’s very personal: you and others are struggling to discover your own power: your power to stay.

Home in the expansive sense of care and dignity isn’t at all easy to come by here. Indeed, it’s getting harder and harder to create and maintain anywhere, everywhere, precisely because of all that you and your neighbors are witnessing daily.

In the concentration camps of Nazi Germany, alongside the Muselmann, there were those who knew they were likely going to die, but weren’t resigned to losing themselves in the process. They schemed about what resistance looks like when they themselves might not survive. In Auschwitz, some Jews assigned to run the crematorium, themselves slated for death every month or so, replaced by other Jews, settled on a plan to destroy the ovens. They assumed they would die in this act of sabotage and defiance, but they would do so on their own terms. They discovered their power to stay human. At least one of them set about collecting stories on found scraps of paper, and then secretly burying these stories — of flesh-and-blood people, their lives, loves, and cultures — in metal cans buried in the camp’s trampled ground, in hopes that when he and others perished, there would still be memory of a people and its culture. At moments, witnessing is resistance.

You may yet be a witness, to the end of your home, the end of many others’ homes and lives. That’s the all-too-likely endgame. But now you are convinced, because many of you are convincing each other, that you don’t want it to be that moment. You have not been reduced to hapless witness, at least not yet. You still have the strength within you to reside in this homey neighborhood as participant, with many other participants, who voice one loud, resounding “Enough!”

The power to stay is, in essence, the power to retain one’s humanity, one’s agency, autonomously and collectively. It is to remain caring and empathetic toward others, against forces that would beat the neighborliness out of us, take all we have, including our spirits, our souls. So for now, you join in with others to find a key to unlock the mystery that none of you know the answer to — yet. You spin stories of future and rebirth: eminent domain, community- and worker-controlled cooperatives, squatting, neighborhood assemblies, land trusts, commons. . . .

You experiment with the power to stay.

* * *

(Photos by Cindy Milstein: wheatpasted poster on the wall of the former cop shop on Valencia Street; disappearing mural in the Mission, buffed over; newly opened Vida sales gallery on Mission Street, next to offensive under-construction complex; another wheatpasted poster from the Valencia Street wall of former cop shop; handmade sign held up at 24th Street BART plaza at start of another Eviction Free SF defense rally to keep someone in their home; portion of a mural and window reflection near Cesar Chavez Street; fragment of another mural, recently painted at 25th and Mission Streets, that includes images of blocked buses; and print by Jose Cruz of Yo Soy 132 Bay Area within a small but lovely art show at Niju Gallery on 24th Street — all in San Francisco, April 2014.)