by Matthew Quest

Radical Philosophy Review

Volume 13, number 2 (2010) 191-195

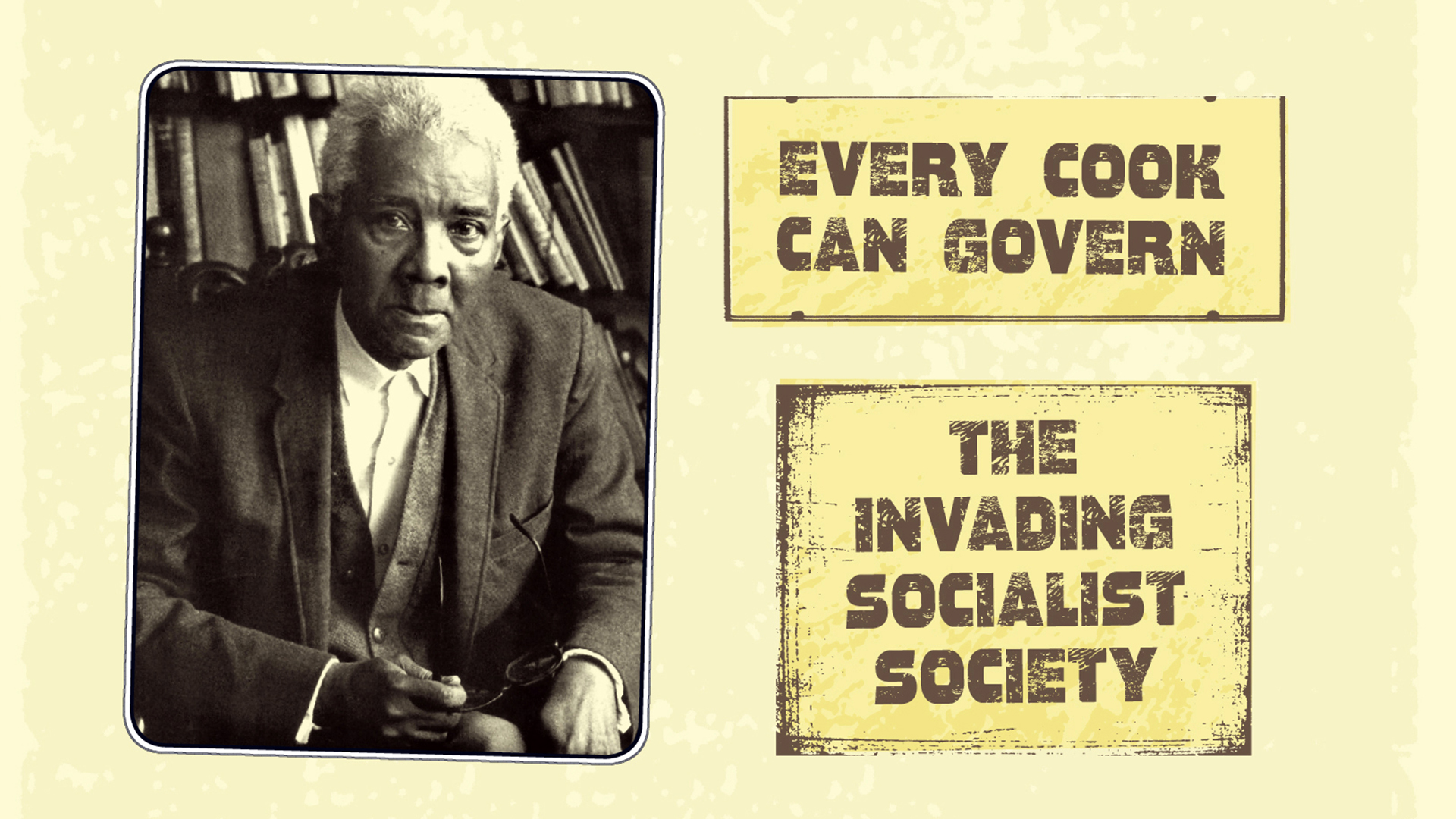

C.L.R. James’ A New Notion, a compiled republication of two of his most engaging and neglected works, which are central to his political thought, will captivate readers concerned with current problems of world war, economic crisis, thin conceptions of democracy, and retrogression from socialist principles. While race and color are not addressed here by this notable Pan-African from Trinidad, it would be a mistake to think they do not address the empire of capital in terms of both imperial and peripheral nations’ experiences.

The Invading Socialist Society (1947), co-written with Raya Dunayevskaya and Grace Lee, is the first collective statement of the Johnson-Forest Tendency of American Trotskyism, and it offers perspectives and proposals that foreshadow a rupture with that movement and most socialist frameworks. James’ small Marxist group would breakaway from the Trotskyists permanently in 1951.

Subsequently, the Detroit based Correspondence group was founded with a newspaper of the same name. Every Cook Can Govern (1956), a meditation on Ancient Athens and direct democracy, first published as an essay in Correspondence, would become an internationally circulated pamphlet. The title itself would become an adage embodying James’ unique body of ideas.

Peculiarly central to his paradigm for national liberation struggles, in exactly that respect, James’ Ancient Athenian framework did not always suggest popular self-management for the Third World. Instead it could be taken as a story there, in contrast to modern industrial nations, reflecting the tasks of an aspiring progressive ruling elite.

The Invading Socialist Society (ISS) cannot be properly understood unless one is aware of James’ view that a socialist future is not distinguished by a one-party or welfare state, but rather the self-emancipation of toilers. Those identifying actually existing socialism with the Soviet Union or Maoist China in the past, or Castro’s Cuba and Chavez’s Venezuela quarrels with American empire more recently, or with increasing access to healthcare and education as the embodiment of a progressive welfare state, while voting for lesser evil capitalist politicians such as Franklin Roosevelt or Barrack Obama, will have difficulty. James is neither concerned with the damaged consciousness of the American toiler or labor globally. It is clear James is not a theorist concerned with cultural or media hegemony like most socialist scholars. He argues, “the theory of the degenerated worker state… implies the theory of the degenerated worker” (54). Consistent with another neglected work, Marxism & The Intellectuals (1962), James does not believe workers need more culture and education over many years before finding the power to emancipate themselves.

Rather, James challenges his fellow socialists on the following grounds. There is no progressive or dual character of government bureaucracy (24). He rejected an odd proposition emerging at that historical moment, but still with us: that the bourgeois police state was a defender of the gains of working people (83).

That such governments could suppress mass movements and still be credited with redistributing wealth and being radical or even viable. A socialist future would for James not place an emphasis on greater economic equality or the cultivation of public or nationalized property, but center on toilers controlling the social relations of production and society by popular councils and committees. “The revolt,” he declares, is “against value production itself” (43).

James illustrates Marxism, for most, had become the analysis of bureaucracies, instead of the instinctive or spontaneous drive toward workers’ autonomy. Noel Ignatiev, in a concise, though primarily biographical, introduction, is correct that James’ conception of revolutionary organization is to assist in disciplining spontaneous revolt. Through education and propaganda James aspires to undercut those who aspire to enter the rules of hierarchy. But Ignatiev does not face squarely a historical dilemma. James functioned in his career both as a mentor of self-emancipating toilers from below and aspiring rulers above society.

ISS is a text which rejects the idea of a progressive ruling elite as it advocates self-government through workers councils. ECCG while promoting the idea of a direct democracy by popular assemblies imagines a place for philosopher-statesmen at the rendezvous of victory. James asserts that “state capitalism,” the increasing government intervention in the world market and ownership of production, was appearing all over the world without releasing the reins on toilers’ lives. It may call itself fascism or nationalism here, socialism there, or communism somewhere else.

But he warns the idea of the progressive ruling elite, whatever form it takes, defends “statified production” against the self-government of working people. Thus, following a phrase from Frederick Engels’ Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, the “invading socialist society” will be where workers begin to take over “people’s” factories, mines, oil wells, and land. The state monopoly of capitalist production, without any plan for cultivating people to directly govern, will be confronted. “Proletarian nationalization” of property, by general strikes and people’s communes, will conquer the aspiring bosses.

ISS is also remarkable for its global reach in analyzing American imperialism as well as the Soviet Union. Further, it repudiates the nationstate as unable to provide economic prosperity and collective security in the world. James’ takes to task the State Department, World Bank, Marshall Plan, and the supplying of arms and resources to “every counter-revolutionary regime” on the globe that suppresses mass uprisings. James asserts the United States dominates its subordinate allied nation-states as it counter-attacks rival imperialisms. The U.S. “engender[s]hatred among revolutionary forces everywhere” in an interplay of “national, imperial, and civil wars,” which will lead to its collapse, just as the Soviet Union in its fraudulent claim to be a workers’ republic will also implode. The Soviet Union and the U.S. have in common, for James, the claim for progressive patronage toward the working class, as it manages them as commodities or national capital. At home they offer bourgeois-democratic or economist reforms while abroad they offer aid —all in exchange for submitting to their world dominance.

James

may appear to observers as utopian, abstract, and sectarian. Yet his

interlocutors made these claims in 1947. He argued, in the rhetorical

flourishes that spice his writings and make them sizzle, that whoever

claimed to be militant and believe in the coming downfall of world

civilization while finding it abstract that working people could

directly govern by popular committee, carry out armed self-defense, and

control production, were “playing with revolution.”

Every Cook Can Govern

(1956), a meditation on the Ancient Athenian city-state, proposes

ordinary citizens can directly govern through popular assemblies, just

as their human ancestors. James knows this would flummox the average

AFL-CIO bureaucrat in the United States or British parliamentarian.

Consistent

with the ISS, James believes ordinary citizens can make economic

planning decisions. In Athens they also made decisions about war and

foreign policy. In a fashion reminiscent of the Apollo Theatre in

Harlem, they also decided what popular artistic achievements, such as

the plays of Aeschylus, would be award winning, and these same plays

would later be interpreted falsely as elite Western classics beyond the

ken of the rank and file. James has been criticized (despite his

acknowledgement of the problem in the text) as minimizing the exclusion

of slaves, immigrants, and women from Athenian citizenship. James has

challenged those who make this criticism by emphasizing they are less

concerned with those who were subordinated in history than in making

sure contemporary democratic conceptions stay minimal. In the post-

Black Power and post-colonial world (if we have arrived there), we need

to interrogate this problem further by centering James’ projections of

Athenian ideals into the African world. The critique of Eurocentrism by

thinkers fond of the progressive character of the nation-state in

certain sectors needs to be taken further.

Every Cook Can Govern,

while functioning as a text intended to give a historical basis for the

ideals of workers self-management in the United States (though James

acknowledges Ancient Athens could not be socialist as it was a

pre-capitalist society), largely has had a different function in the

Caribbean.

Aspects of his argument can promote a sense of

national purpose—the small islands imagined as similar sto their Greek

counterparts—if the aspiring “city-state” and its leadership cultivates

the humanistic development of the masses. What could this possibly mean

after James has generally rejected social democratic economism and

cultural criticism in the former text? Here we should be aware of James’

references to Pericles: the famous statesmen in his Funeral Oration

suggested the noble character of the Ancient Athenian citizen was not

that all could make policy, but that all could judge it.

James’

meditation on Ancient Athens inaugurates a shift in his political

thought, always incomplete, between a syndicalist vision of popular

committees of self-governing workers and an increasing focus on

philosopher-statesmen, especially those in the Third World, such as

Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah, Trinidad’s Eric Williams, and Tanzania’s Julius

Nyerere. In a fashion akin to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, they should observe

the self-activity of the popular will, which doesn’t know exactly what

they desire (though this doesn’t make them dumb or mis-educated), as

they appear to embody in their actions the condemnation of

representative government. Still postcolonial statesmen can be imagined

as progressive and leading a revival in their initiation of the

post-colonial defeat of the plantation order. And this should be part of

an unanswered riddle: what happened to the Grenada Revolution,

which critiqued the Westminster model and advocated popular assemblies

instead? What exactly was C.L.R. James’ influence on Maurice Bishop?

These texts are suggestive.

We

will conclude by reminding ourselves how James and his associates

projected these ideas into the West Virginia coal fields against John L.

Lewis’ United Mine Workers’ trade union bureaucracy. Also these

inspired perhaps the most original theorist of the Black Power movement,

the African American autoworker James Boggs, to break with Walter

Reuther’s United Autoworkers’ hierarchy in his earlier labor activism in

the Detroit of the early 1950s. Observers of the post-colonial moment

in Caribbean political thought should be aware of how James’ ideas on

popular assemblies and workers councils, evident in these two seminal

works, shaped projects fighting empire from above and below society.

Eric

Williams’ effort to be a populist tribune of the people of Trinidad

from 1955 to 1961 would decline and evolve into the Black Power revolt

of 1970 against his post-colonial regime. Both moments have linkages to

these intellectual legacies of James as the following one. Eusi

Kwayana’s African Society for Cultural Relations with Independent

Africa, from 1971-1974, in its transition from party politics to a

movement of popular committees of bauxite and sugar workers against

Forbes Burnham’s regime in Guyana, facilitated their own invading

socialist society. Self-managing workers took over nationalized property

and foreshadowed the epic struggle, led by Walter Rodney, for people’s

power and no dictatorship in a postcolonial society.

These two

works from C.L.R. James’ archive, if critically engaged, will prove to

be an archive of new notions for philosophical criticism and social

movement practice, wherever the re-enchantment of workers power and

Black autonomy beyond the nation-state and the empire of capital are

found to be desirable.

Back to C.L.R. James’ Author Page | Back to Noel Ignatiev’s Author Page