Originally posted in

Mystery Readers Journal

Volume 32:2:

New York City Mysteries II

I come from a family of New Yorkers. Three of my grandparents emigrated to the city from Poland and what is now Belarus and lived there most of their lives, the fourth was born there, and both of my parents were born and raised in Brooklyn before it was cool, uncool, then cool again. So I’ve seen the city in many incarnations, from a glittering jewel to a busted-down trash heap to the Disney version of Times Square on display today. Nowadays, crime in NYC is down to historic lows, but from the mid-1970s to the early 1990s, it was the Wild West.

I lived in the fabled Punk Rock-era East Village and then Inwood in northern Manhattan for a good chunk of this period, when NYC was still recovering from the fiscal crisis of the mid-1970s (as embodied by the Daily News’s famous headline FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD). It was a crazy time: huge swaths of the South Bronx were burnt out and abandoned, and the subways were filthy, covered with graffiti, broiling in summer and freezing in winter, and late at night the transit cops didn’t even bother going into the last car on the Number 5 train, known as the “party car,” where marijuana was openly smoked. These days, I am still astonished when I step into a gleaming, air-conditioned Number 1 train.

It was a tough time for cops, too, who spent 99 percent of their time answering 911 emergency calls, so they had no time for relatively minor infractions, or even some relatively major ones. I once spent a Saturday evening watching the action on Avenue B in the East Village. This was long before cell phones, so there was a crowd of at least twenty drug dealers hanging out by the pay phone on the southeast corner of Avenue B and East 11th Street. And I watched as a patrol car drove by on East 13th Street, then East 12th Street, then they skipped East 11th Street and drove by on East 10th Street. They clearly knew what was going down on that corner (I figured it out the minute I saw it), and they simply decided to avoid it completely.

Can’t say I blame them.

This was a time when the blocks got progressively worse as you headed east from Avenues A through D to the FDR Drive along the East River, and people used to joke, “A you’re Adventurous, B you’re Brave, C you’re Crazy, D you’re Dead, and FDR means Face Down in the River” (or alternatively, Found Dead in the River). Real estate ads for apartments in the area included info such as “good block,” but if it said “good building,” that meant most of the other buildings on the block were bricked-up shooting galleries.

Punk rockers going to the S.I.N. Club (the acronym stands for Safety In Numbers) on East 3rd Street near Avenue C were advised in the club’s newspaper ads to “walk up C” from Houston Street in order to avoid the worst stretches of Avenue C.

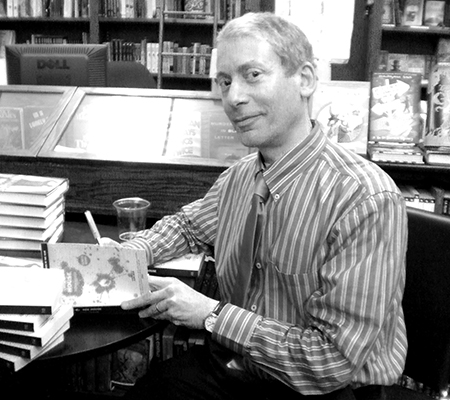

Even then, I knew these experiences were going to find their way into my novels, beginning with 23 Shades of Black (an Edgar Award finalist for Best First Novel), in which my series character, Ecuadorian-American police officer Filomena Buscarsela, expresses precisely the ambivalence toward risking her life to bust small-time street dealers that I witnessed first hand on that Saturday night so many years ago. I met so many colorful characters on the streets that I continued to draw on them for years, peopling the pages of my novels with authentically multicultural characters—not just to be inclusive or PC, but because this is an accurate reflection of the demographics of the working-class neighborhoods I lived in. The years I spent in the heavily Dominican area of Inwood also influenced the creation of my Latina heroine, and the plot of my second novel, Soft Money, is based on the actual murder of the hard-working Latino proprietor of a convenience store that I frequented. And yes, I knew the guy.

Then there are the funny-crazy bits, like the man standing on the corner of Broadway and West 207th Street one morning who kept raising his arm to women crossing the street and singing, “There she goes, Miss A-mer-ica,” as if he was hosting the famous beauty pageant. Never saw him again, but he made it into my third novel, The Glass Factory.

In the mid-1990s, I went back to graduate school and ended up teaching Freshman Composition as an adjunct professor at Queens College for two years, where my classes looked like the General Assembly of the United Nations. (Queens is the most ethnically diverse place of its size on earth, with more than 80 languages spoken in the borough.) Talking to beat cops and walking through the different neighborhoods, including the large Ecuadorian community in Corona, provided me with essential background material for my fourth novel, Red House, which led to an invitation to contribute a story to Akashic’s Queens Noir anthology.

All in all, you couldn’t ask for a better incubator of crime stories than New York City during that wild and crazy period before the city’s “recovery.” The city is much cleaner and safer these days, and very few people are nostalgic for the bad old days, with the exception of the artists, musicians and writers who could still find affordable apartments on the edges of some seriously sketchy areas, seeking inspiration and safety in numbers, and screaming against the juggernaut of Reaganomics and the nightmarish scenarios of megadeaths in a nuclear war whose only survivors would include swarms of irradiated cockroaches. Beyoncé sure looks great when she’s grinding out the Super Bowl halftime dance steps dressed in a black leotard and fishnet stockings, but my pulse still quickens when I hear the Dead Kennedys’ invitation to lynch the landlord, spend a holiday in Cambodia, and kill the poor with neutron bombs.