by Adam Dunn

Marx & Philosophy Review of Books

June 18, 2012

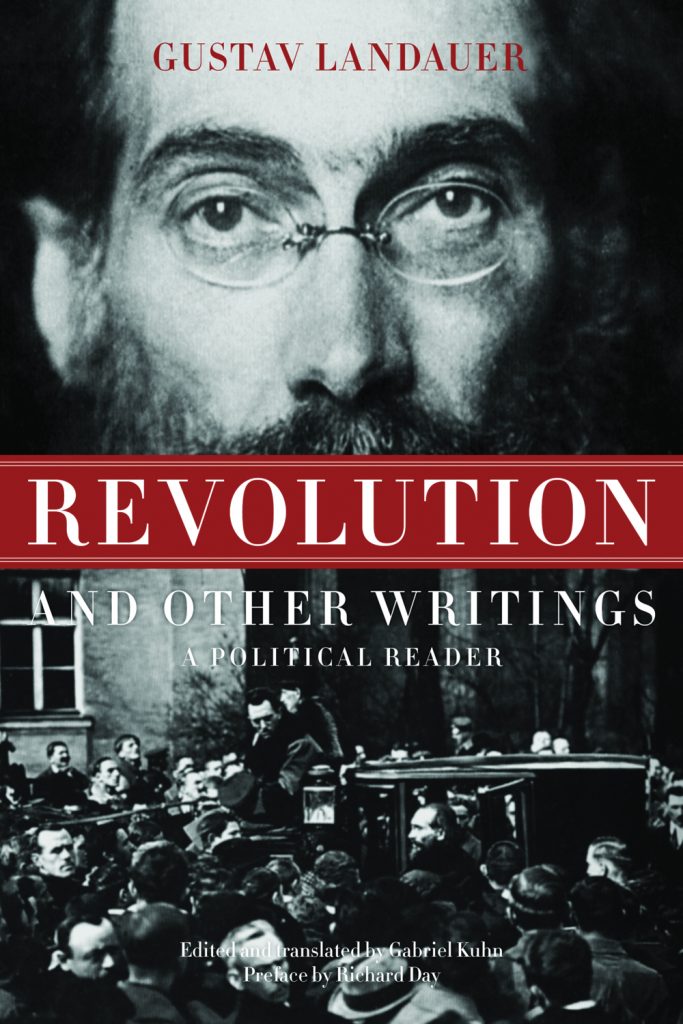

Gustav

Landauer (1870-1919) was an anarchist socialist who opposed the use of

violence and thought anarchism and socialism to be essentially linked

(more on this below). His involvement in the Bavarian Council Republic

led to his murder at the hands of SDP and Free Corps soldiers. This

edited collection remedies the lack of English-language translations of

Landauer and is an interesting example of a strain of socialist thought

that wants to do without the state. The editor provides both a general

introduction (thirty pages) and short introductions to the individual

pieces to help the reader unfamiliar with Landauer. The introduction

moves swiftly enough, and ends with a short section on Landauer’s

posthumous influence; this is useful, providing enough context for even

the non-academic audience the publisher seeks. Kuhn also gives both a

generous supply of explanatory footnotes and an explanation up-front of

words difficult to render in translation. The volume closes with a

comprehensive (German and English) bibliography of works by and about

Landauer. These supporting materials are very helpful, especially given

Landauer’s relatively low profile.

The selection is from Landauer’s “political,” rather than “literary/cultural” or “philosophical” (10) writings. This selection principle is quite inclusive, with political philosophy presented alongside Landauer’s more practically-oriented pieces, which include letters, articles, statements of political goals, and commentary on particular events. The writings are organized into groups; the earlier groupings are basically chronological, the latter ones thematic. (The first piece in the volume is a reflection by Landauer on his youthful development.) The chronological groupings, organised as they are around phases of Landauer’s life, also have high degrees of internal thematic coherence.

The same is true of Landauer’s works as a whole, which exhibit a high degree of consistency of interests and positions across the course of his life. His fundamental commitments are to both anarchism and socialism together, treating them as co-dependent. This combination is fundamental to Landauer’s thought. His clearest (and earliest) statement of this comes in “Anarchism-Socialism,” a piece written to explain adding the word “anarchism” to a journal’s subtitle. That relationship is expressed thus: anarchism is the end for which socialism is the means. For Landauer, freedom is primary and “solidarity, sharing and cooperative labour” will secure it (70). This link is intrinsic, he says: genuine cooperation is possible only amongst the free and freedom is only possible when “needs are met by brotherly solidarity” (70). This alternative to centralised planning (as well as to ‘every man for himself’) is to take the form of associations related to particular interests that involve all those affected, leading to a “free order of multiple, intertwined, colourful associations and companies” (71). There is something attractive about this network of specialised organisations, particularly because through it Landauer recognises the possibility of overlapping memberships and struggles. The difficulty comes in the attempt to address larger-scale interests: co-ordination between different groups will be possible, Landauer thinks, “because necessity demands it” (72). His example of this is train scheduling, which invites, I think, a certain pessimism.

His other group of examples includes both “measurements” and “statistics,” which he thinks are not important enough to serve as a base for “global domination” and likely to fall under management by some group without political influence (72). Landauer is here being a bit naive. Any statistical measure accepted as authoritative will shape related behaviours in some way and with this give some power to those in charge of determining the measures. This is related to the main problem with this piece: Landauer’s positive account of anarchist organisation without any form of coercion—even the use of social pressure—is more hope than detail and, at the limit, looks suspiciously similar to faith in the “free market.”

The single largest work in the book is Revolution (110-85, including endnotes). It is also the hardest part of the book to get a good hold of. Kuhn quotes and agrees with Ruth Link-Salinger’s claim it is a “poorly constructed” work, and adds to it a charge of terminological inconsistency (30). The first of these two problems is more severe: Landauer covers a lot of ground, without offering much sense of how it all fits together. Landauer does not think explanatory laws of history will help at all (114-7). Instead, he claims, there has only been one true revolution, “the so-called Reformation,” of which we are still a part, which makes scientific investigation impossible (120). Instead, Landauer presents something like an historical survey, including an attempted rehabilitation of the Middle Ages as an era of “ordered multiplicity” (130), “the only heyday of our own culture” (126). His Middle Ages are the birthing-time of individual freedom against ‘social and spiritual bondage’ and thus the true start of revolution (126). Landauer’s Middle Ages are idealised: a complaint that Kuhn repeats and provides example sources of (30). But his version of the Middle Ages is explicable in light of his idea of the past as something subject to change, malleable by our own current interests and also alive through them (120-1). The past he describes (and effects) is the living past he wishes to bring about. His idealised description is meant, I think, to help bring about revolution after his own idea of it as a time in which all are full of spirit (146). I am far from confident in this reading, however; this is a difficult text that needs a much clearer sense of purpose.

The earlier piece ‘Through Separation to Community’ provides a clearer vision of what Landauer means by “spirit.” He sets out his opposition to seeing the individual as starting point of reflection, as it inevitably closes us off from the world (97). He replaces it with a mysticism of the infinite world which we ourselves are (98-9). Each person, if living fully, somehow incarnates their community; the wrong of the authoritarian state is that it separates us from this (106-7). There is at least an intuitive plausibility to the idea that our existence as legal and economic subjects is a reductive picture of human beings, missing out on vital elements. Here, Landauer combines it briefly with a Nietzsche-influenced distinction between the new (socialist) human being, who is up to the task of living fully, and the masses trapped “deformed” by the state they want to keep (107). The latter are, he thinks, beyond help; they ‘cannot shed their masks’ and must be left behind (107). The only test of which class a person belongs to is their willingness to live without a state.

Other than the theoretical works, this collection includes Landauer’s reflections on world events. This includes a touching tribute to the Haymarket Martyrs. It also includes a piece, ‘McNamara’, in which Landauer sets out his opposition to the use of political violence, treating it as a method of party leaders, rather than true socialists (255-60). There is also his strident opposition to Esperanto because it is a purely artificial language (276).

Also included in the collection are some of Landauer’s letters. Some relate to his involvement in the Council Republic; others include, rather morbidly, the last letters written before his murder. These are only really of interest to the Landauer-completist.

A letter to Buber in November, 1918 (318) contains two points of interest. First, that Landauer ‘would not condemn any act of violence that helps destroy’ the old press to make way for a new one, evidence that his opposition to violence is not absolute. But this also leads into his suggestion of an advertising monopoly by the state. At that point, that would mean giving ‘the workers’ and soldiers’ councils’ this power, which harkens back uncomfortably to the sort of behaviour Landauer earlier associated with party politics and the state. This would, perhaps, be excusable but for Landauer’s earlier insistence that the anarchist approach is distinctive from the state’s coercive methods. The second point of interest is one of consistency rather than change: he writes against establishing ‘intellectual councils’ separate from other workers’ councils, calling it ‘pompousness’ and proposing that workers, both manual and intellectual, should be united in the same council bodies. This resonates with his claim that spirit is the most important element for social transformation, with Landauer’s preference for a dispersed spirit, rather than isolated ‘genius’ figures.

Landauer’s written voice makes for easy reading. And, outside of Revolution, clarity and straightforwardness is the rule. This alone would not be enough to recommend the book, but Landauer’s combination of socialism and anarchism makes for interesting reading. The pieces where he applies himself to practical matters, or to the analysis of events, are also worth reading; his place in the history of the inter-war workers’ councils secures this much. Landauer’s work is not a systematic account of non-state socialism, but it is an interesting step in the historical evolution of such accounts, married to a sound awareness of the importance of instilling what might elsewhere be called an “ethos.”

Back to Gabriel Kuhn’s Author Page | Back to Gustav Landauer’s Author Page