By Sasha Simic

Socialist Review

September 2012

The Russian Revolution of October 1917, which ended the situation of dual power in favour of the workers’ councils (soviets), was never intended to be confined within Russia’s borders.

Germany, as one of Europe’s most industrially advanced nations, was seen as a key battleground for the future. And almost a year after Russia’s revolution the Bolshevik strategy was vindicated by the German Revolution of November 1918. Initially the German Revolution seemed to replay events in Russia, but with the prospect of a far easier transition to full workers’ power.

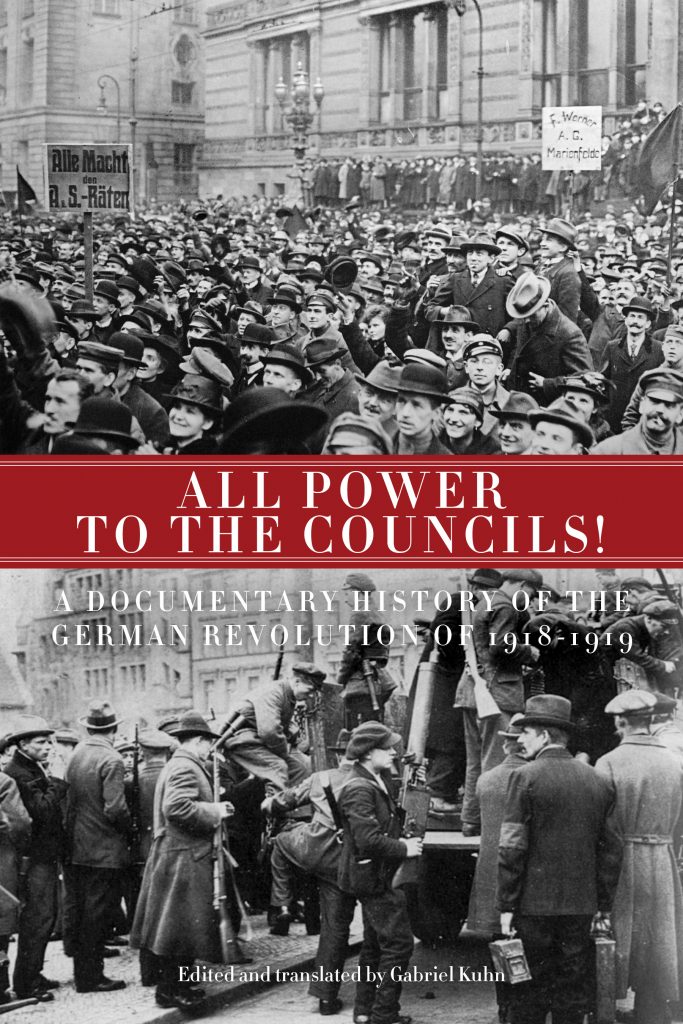

This book presents a groundbreaking documentary history of the workers’ councils that emerged. Included are the most fascinating speeches, articles, programmes, letters and manifestos.

The revolution advanced rapidly throughout Germany. On November 9, Philipp Scheidemann of the socialist, but reformist SPD, announced from Berlin that Germany was a parliamentary republic. Meanwhile the revolutionary Karl Liebknecht declared Germany to be a socialist republic.

But which one was it to be?

The next weeks and months would witness a struggle for the future of Germany. Would it become a bourgeois parliamentary republic under the “control” of left wing ministers or a socialist republic under the direction of the workers’ councils? The question was settled in December 1918 when the Congress of Councils voted to liquidate itself. This was a triumph for the leadership of the SPD.

The anarchist Gustav Landauer, who played an honourable role in the council movement, declared, “I know of no more disgusting creature than the Social Democratic Party.”

One SPD minister, Gustav Noske, conspired with the army command to physically eliminate revolutionaries, declaring, “Someone must be the bloodhound.” As a consequence of working class loyalty to the SPD all of these figures had key positions within the councils and they used their influence to demobilise the working class.

Karl Liebknecht exposed their calls for “unity” on the left: “They want to steer the movement into ‘quiet waters’ in order to save the capitalist order. They want to take power out of the workers’ hands by re-establishing a political order based on class and by defending an economic order based on class.” That they did. And they triumphed. The councils were wound up.

The failure to build a credible alternative to the SPD cost Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht and 2,000 revolutionaries their lives.

This book presents a wealth of information about how the councils worked, what they stood for and how they were undermined. Editor and translator Gabriel Kuhn is to be congratulated for collecting a broad range of memoirs and commentary on the period from people who were at the centre of the revolution including brilliant and stirring accounts from Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht.

I didn’t agree with the political conclusions of many contributors—some wrote their memoirs many years after the facts and with a clear political agenda. The best reports are those nearer the events of this great, tragic episode of working class history. Read it to get a flavour of a time when we came tantalisingly close to taking power in one of the most advanced countries in the world—an episode which left us with the biggest “what if” we can ask of history. Read it to prepare for the next time so we won’t be fooled again.