Twenty-five years after launching AK Press, Ramsey Kanaan took his democracy elsewhere.

By Rachel Swan

East Bay Express

February 18th, 2009

When Ramsey Kanaan launched the anarchist publishing company AK Press 25 years ago, he created a truly egalitarian business model: no hierarchies; no staggered wages; no CEOs making decisions in far-removed corporate offices. In fact, all decisions would generate from within, and only be implemented after a majority-rule vote. Such a system, while idealistic, seemed the only way for Kanaan to properly apply his personal politics to the business. A committed anarchist who had grown up in the punk scene, Kanaan couldn’t envision any work setting that didn’t embrace democracy — even if the term “anarchist business” seems counterintuitive (as AK readily points out on its web site). After all, if you can’t find equality in the business world, why not impose it?

His idea proved successful, and to this day, AK still operates as a worker-run collective with chapters in Oakland and Stirling, Scotland. But Kanaan jumped ship in 2007 to form PM Press, a similarly styled publishing enterprise run by a group of like-minded anarchists, most of whom had been affiliated with AK at one time or another. The difference, he said, is that PM is willing to explore new media and new modes of distribution, and expand beyond the hard copy realm. Kanaan had tried for several years to bring his new vision of publishing to the folks at AK, but he could never get the majority to go along with him. Eventually, Kanaan got tired of being overruled. The democratic system he had set up was the thing that drove him out in the end.

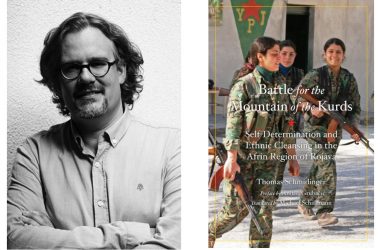

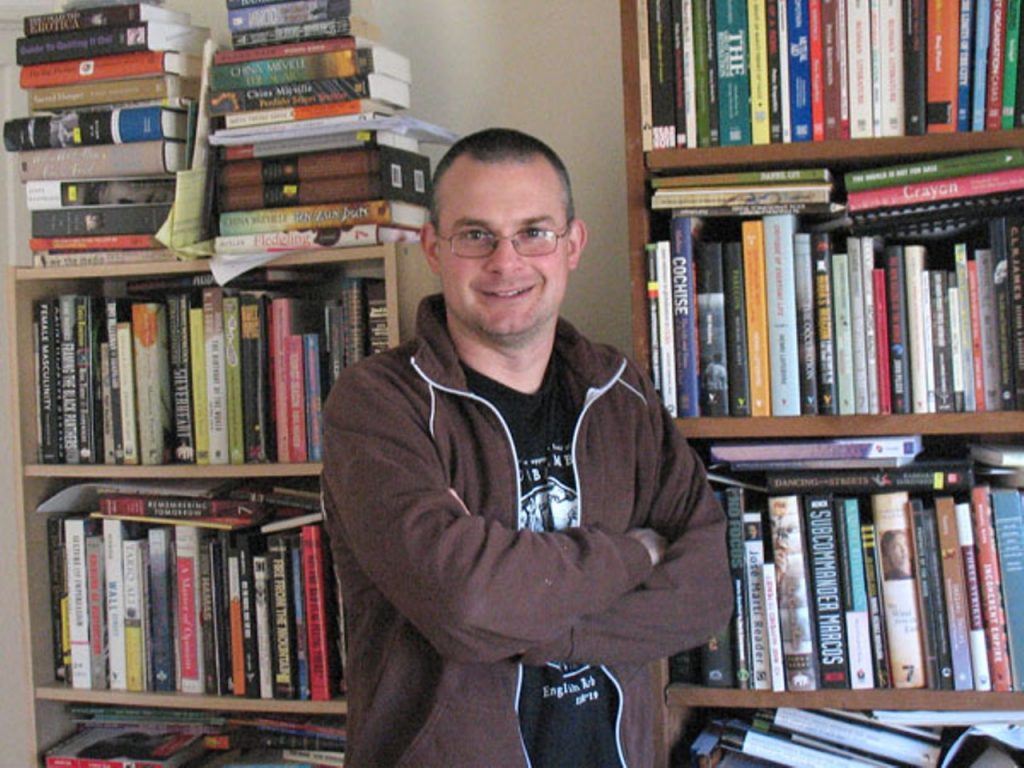

Kanaan said it’s for the better. The 42-year-old veteran publisher currently runs PM from his small West Oakland apartment, whose wall-to-wall bookshelves brim with titles that reflect his radical sensibility: Inside Hamas; Tolstoy the Rebel; I, Shithead: A Life in Punk. It’s an incredibly small, all-volunteer operation; Kanaan said he plans to start paying wages this year. If you call the phone number on PM’s web site, you’ll reach Kanaan’s home answering machine. He processes orders at home, manually tallies his inventory, and conducts most business on his personal computer. About six people participate in the day-to-day editorial decisions at PM, and tag-team on editing and copyediting. Kanaan and fellow Oakland resident Dan Fedorenko are the de facto customer service reps, and Fedorenko handles most of the mail orders. Because of its size the group makes decisions collectively, using a model that’s similar to, if not more liberal than, the one at AK. It’s worked so far because they pretty much agree on everything, said Kanaan — including the fact that no one’s in there for the money or the glory.

Material gains were never part of publishing for Kanaan, who got into the business at age thirteen in his hometown of Stirling. He had just gotten into punk rock and anarchism, two counterculture movements that seemed intertwined, he said. “I was playing in a punk rock band and I started selling fanzines. As I got exposed to more overtly political literature, I started selling that.” Kanaan describes himself as less a self-taught impresario than a very inquisitive sponge. “I was the annoying fifteen-year-old who would go up to people and bug them and say, ‘How do you do this, and how does this work?'” Kanaan recalled. “I’d walk into a bookstore with a bag of stuff to sell, and say, ‘Hey, do you want to buy some, Mister?’ They’d say, ‘Actually you have to make an appointment with the buyer.’ I’d say, ‘Oh, okay. Can I make an appointment with the buyer then, please?’ I’d come back next Tuesday. I have no experience other than trial and error.”

He founded AK Press in the mid-’80s and named it for his mother, Ann Kanaan. Initially a one-man mail-order business run out of Kanaan’s house in Stirling, it became a genuine worker collective in 1989. That year Kanaan traveled to the US with his punk band, Political Asylum, on a tour that culminated in San Francisco. There they attended a week-long anarchist conference called Without Borders, and played a rowdy warehouse show at 17th and Shotwell streets in the Mission. Kanaan was bedazzled. He ate his first burrito at Pancho Villa’s and became an instant fan of taqueria food. Not to mention he was enamored of San Francisco’s warehouse punk scene. (The concept of “playing in someone’s house” was novel.) Five years later, Kanaan managed to convince the other folks at AK that the company did enough business in the US to open a San Francisco chapter, and that he would shoulder the onerous burden of moving out there.

At that time, said Kanaan, AK was still ahead of the curve in terms of exploiting new technology. AK was one of the first businesses to record lectures onto CD and distribute them to record stores. Not to mention the company had a web site and e-mail addresses pretty early on, thanks to some friends at MIT. (Kanaan began using e-mail in 1995, back when most people’s addresses were “insane clunky things with 27 digits and numbers.”) In 2000, AK was dot-commed out of San Francisco and forced to move to its current West Oakland location — an old auto parts warehouse on San Pablo Avenue. Low overhead and strong name recognition helped it weather the turbulent economy for a while, but as time wore on AK stopped making technological innovations.

For years the company survived on a fairly simple, indie-bookstore format: A catalog comprising books, ‘zines, gear, pamphlets, and DVDs, combined with regular events (lectures and book sales) that lured people out to the store. As people started getting more information online, Kanaan found it necessary to update that formula. He wanted AK to record its lectures and sell them as digital downloads. He thought the collective should expand its inventory to include fiction novels and e-books, plus a wide selection of music CDs and DVDs. He initiated several discussions about increasingly AK’s presence online, but said most of them went nowhere.

Kanaan couldn’t convince his comrades to respond to the exigencies of a rapidly changing industry. And over time, he said, it got harder and harder to maneuver within the entrenched democracy of AK. “My problems with AK are not with the decision-making structure, it’s just that at a certain point, there’s only so long that someone can be in the minority,” Kanaan said. “We had a difference of opinion as to how to proceed.” Ultimately, he said, it was an amicable split. In a recent e-mail, AK Press member Suzanne Shaffer assured that the two publishing companies still work closely together, and that there’s no bad blood between them: “We make all our publishing decisions democratically, so of course we don’t always agree on everything and getting outvoted sometimes is a fact of life,” wrote Shaffer. “Ramsey did have lots of ideas for titles he wanted to publish, and some of them fell outside of AK’s sphere (as a collective, we prioritize publishing anarchist history and theory).”

PM Press was born of a 25-year itch. It has all the attributes that helped AK at its inception: inexhaustible creativity; a staff of idealists willing to volunteer their time; imaginative ways of bringing print to the digital realm. In its first year of existence the company published roughly a dozen books, including comics, a crime novel series called Geek Mafia, a photo anthology of graffiti by the UK aerosol artist Banksy, and a book of postcards by Eric Drooker, all of which are available as e-books. The new collective also produced a slew of CDs and DVDs, and plans to implement more ideas in the coming year, such as author blogs, downloads, and book “extras” (i.e., supplemental interviews and commentary). Kanaan said he’s happy to no longer be pigeonholed as “anarchist” (both a blessing and a curse for AK), and to be interacting with new forms of media.

He’s also pleased that most of his ideas actually see the light of day. “It’s not that I want to be a dictator,” said the publisher, explaining that PM is in fact more collectively minded than AK. It’s just easier to run a collective when everyone agrees with you.