As the broader publishing world flounders, alternative presses are turning to their communities for support.

By Anna Clark

The American Prospect

December 3, 2009

“When I get a little money, I buy books; and if any is left I buy food and clothes.” So said Desiderius Erasmus, a Dutch priest born less than 20 years after the printing press was invented. This holiday season, publishers might like to see his ilk in bookshops. Traditionally, the book industry depends upon the December gift-giving season to buoy its entire year. Many publishers shape their catalog around the six-week window of intensified shopping that carries particular urgency in the depths of a recession.

But this “make or break” bookselling strategy is one holiday tradition that a handful of innovative publishers are eager to end.

In search of sustainability, some publishers and booksellers are adapting ideas from the food movement. Community-supported agriculture (CSA) — in which consumers buy a share of a farm’s produce yield for the season — translates to community-supported publishing (CSP), in which readers subscribe to an independent press that in return delivers books to their doorstep every month. “Buy Local” becomes “Buy Indie.” And the do-it-yourself momentum behind home gardening parallels the energy behind literary chapbooks, a traditional form that’s finding new popularity and legitimacy in the 21st century. More than a marketing strategy, the sustainability shift is carving out a place for diverse ideas — even in an economic climate where mainstream publishers abhor risk.

South End Press is among those that are crafting alternative models of publishing. The nonprofit, collectively run press has an author list that includes Noam Chomsky, Cornel West, bell hooks, Howard Zinn, Arundhati Roy, and Vandana Shiva. Founded in 1977 in Boston, South End opened a second office in Brooklyn this year to better situate itself financially and as a movement-builder.

The inspiration behind the CSP program is clear. South End’s Web site invites potential subscribers to enjoy “a steady crop of books” that feature “all the new varieties and choice heirloom selections free each month.” CSP subscriptions start at $20 per month. Members receive a book each month and a 10 percent discount on all further purchases; when no new title is available, members get an item from South End’s backlist that is deemed to be timely. During this year’s health-care debate, CSP members received Sickness and Wealth: The Corporate Assault on Global Health, a 2004 anthology of essays.

Asha Tall of the South End collective said that the publisher explicitly borrowed from the food movement’s CSA model when it developed its community-supported publishing program in 2006. “We were looking for ways to engage more directly with readers,” Tall says. At the same time, Tall adds, the CSP program was intended to “relieve the effects of the consolidation of book distribution.”

With about a hundred CSP members, South End can count on a certain number of sales up front, allowing it to effectively underwrite its projects. The program brings in money throughout the year from supportive readers, rather than depending on the whims of holiday shoppers. Alex Straaik, an editor at South End and a collective member, says that “with a holiday gift subscription drive and by spreading the word to our new allies in Brooklyn,” the publisher intends to significantly grow the program.

South End is looking for people like Soula Pefkaros, a 28-year-old activist in Virginia who is the creator of a documentary photo exhibit about “small ecologically conscious farming and the people building an alternative food paradigm,” as she describes it. Pefkaros is willing to apply those beliefs to her reading habits as well — she spent a year as a member of South End’s CSP program and plans to rejoin soon. “I intend to have a CSP again in the future because, first, it makes me feel good and I enjoy their books; and second, I want to keep supporting an organization that plays such a vital role in meaningful social change,” Pefkaros says. “I really believe in South End Press and what they’re trying to do.”

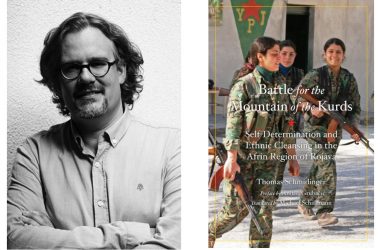

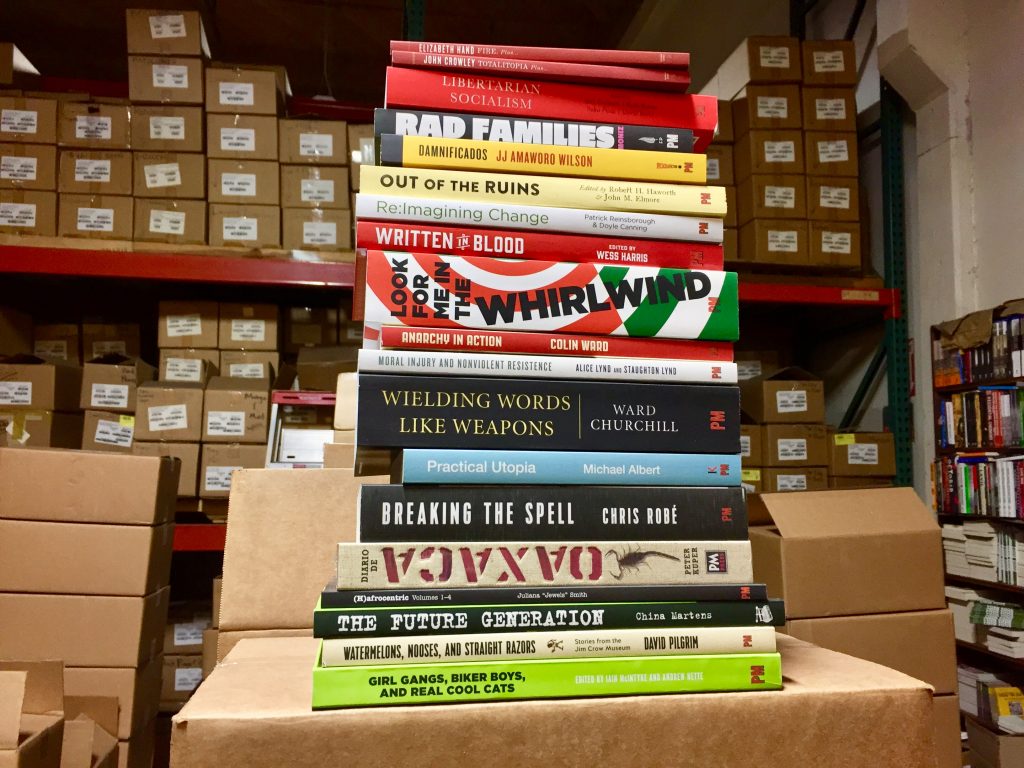

And South End is not alone. PM Press, based in Oakland, California, produces books, pamphlets, videos, and audio materials. Not more than two years old, it shares much of its ideals with South End. “We’re a publisher of fine material, with a decidedly leftist, progressive bent,” says PM co-founder Ramsey Kanaan, who brings more than 30 years of publishing experience to this new venture. PM calls its CSP initiative Friends of PM, which offers four membership opportunities for people who want to “help impact, amplify, and revitalize the discourse and actions of radical writers, filmmakers, and artists.” For $25 a month, Friends of PM get either every published book and pamphlet or every CD and DVD, along with a 50 percent discount on anything else from PM. For $40 a month, members receive all PM releases plus the discount. Friends who contribute $100 a month receive all PM merchandise, free downloads, and the discount. About 60 people are currently members of the young program, though Kanaan admits that “6,000 would be nice.”

Kanaan is quick to point out that Friends of PM is a variation on a theme. People used to subscribe to books when titles were serialized and came out in installments. Likewise, listener–sponsored radio has been on the air since 1949. By returning to traditional storytelling models of direct connection, PM Press is both radical and old-fashioned.

“Whether it’s sustainable is still an open question,” Kanaan said. “Whether any media is sustainable is an open question, which is why media is in crisis. Surviving in this climate is a measure of success.”

Lisa Jervis is among those who believe that PM is on the right path. “No one knows what’s happening with print publishing in the long term,” says Jervis, who published her book, Cook Food: A Manualfesto for Easy, Healthy, Local Eating, with PM Press this year. “No one knows what the successful model is, so why not try something? If a measure of success is to get to work on projects that are great and important, then this is a good start.”

Both South End and PM host catalogs that cohere around a commitment to radical social change. But for a general publisher — independent or otherwise — it remains an open question whether this strategy is workable. If the CSP model depends upon the reader’s commitment to the sustainability of the publisher, what happens when the publisher doesn’t have nearly so distinct an identity as South End and PM? “I think it’s a harder sell for the mainstream press,” Tall says. “The idea they push is that they offer a product you want. If it’s only a product, that’s all you will buy from them.”

Kanaan adds that the community-supported model is difficult for traditional publishers due to the inflexibility of corporate culture and to what he calls “the credibility gap.” For readers like Soula Pefkaros, this credibility is the key factor. “I trust South End Press. That is, for me, an invaluable piece of my CSP,” Pefkaros says. “I felt it was one way I could hold myself accountable to educating myself about things that I feel are important.”

To reach readers who don’t necessarily want to make such a commitment to a single publisher, the literary world is also seeking sustainability through the Buy Indie movement. Much like the foodie Buy Local campaign, which urges consumers to support local farmers, Buy Indie spotlights the benefits of local booksellers over chain or online stores. The movement emphasizes how community support leads to thriving local economies.

“Spend $100 at a local [bookstore], and $68 of that stays in your community. Spend the same $100 at a national chain, and your community only sees $43,” touts the Web site of IndieBound, an association founded by independent booksellers in 2008. Though it has expanded its focus to include other community-oriented and independent businesses, IndieBound retains a bookish emphasis. Its Web site features reading-group guides, book wish lists, and profiles of local bookshops. Visitors are invited to explore Indie Bestsellers — drawn from weekly reports by independent booksellers across America — and the Indie Next List of recommended titles.

“Indiebound.org is booming with users,” says Paige Poe, the IndieBound outreach liaison for the American Booksellers Association. She added that the IndieBound application for iPhones is especially popular, along with the affiliate program, which rewards bloggers and reviewers who link to books on indie bookstores’ Web sites.

In that same vein, a collaborative blog titled quite directly “Buy Books for the Holidays” advocates for shopping at independent stores. “What’s at stake is the wealth and diversity of book culture,” wrote author Joshua Henkin in a blog post about the Buy Indie campaign during the last holiday season. “I would especially encourage you to buy books from independent bookstores, which are in the most serious trouble and which promote books that go beyond the usual bestsellers and where the employees really know about books.”

“Independent booksellers are the unsung heroes in what are very difficult times,” Henkin adds.

Indeed, the Buy Indie movement seems to be gaining traction. In last year’s holiday shopping season, independent stores outperformed their chain counterparts, according to a 2009 survey from the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. Stores located in cities with robust Shop Local and Buy Indie campaigns performed best of all. “The success of the local food movement, and the success of independent businesses during the last holiday season, makes us fairly confident that the interest in local will spread to and sustain local, independent retailers,” Poe says.

Just as the food movement is looking back several decades to a time when we ate more sustainably, the publishing world is finding a renewed interest in chapbooks, small volumes of fiction or poetry, often handcrafted and artfully designed, which are available in limited distribution. The chapbook has a storied history — it was the chosen medium for literary classics like T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” and the first edition of Allen Ginsburg’s “Howl.” Now a new generation of writers is embracing the uncommon hands-on creativity that it offers. Last April the City University of New York hosted an inaugural three-day festival called A Celebration of the Chapbook. Meanwhile, there are dozens of prizes that acknowledge the high-quality work being published in chapbooks, awarded by organizations as varied as the Black Lawrence Press, the Alabama State Poetry Society, and the Center for Book Arts.

“With the culture of the low budget and the homegrown becoming ever more appealing in our difficult economic times, and established outlets for literature seemingly diminishing, chapbook publishing, with its do-it-yourself spirit, is on the rise,” writes Kimiko Hahn in the September/October issue of Poets & Writers magazine.

More than a movement of “independence” from corporate publishers and booksellers, this is a movement of interdependence. You might say that these choices — whether they take the enthusiast to homemade chapbooks, indie booksellers, or community–supported publishers — are nourishing a diverse literary ecosystem in which readers recognize their stake in a vibrant culture. After all, we are at a moment of unprecedented corporate-media consolidation; particularly in a recession, there is little room for writers with unconventional or “controversial” ideas in the mainstream press. And yet alternative ideas remain a potent force. As Kanaan points out, “There’s a reason there were book burnings. There’s a reason books continue to be banned around the U.S. and the world, and why Internet access is restricted in China. Ideas are powerful.”