By Joe Gross

The Statesman

April 3, 2011

It’s fitting that Michael Moorcock’s house seems to exist in four dimensions and is weirdly tough to get to.

First, GoogleMaps completely blows the directions to Bastrop, failing to mention an overpass.

Then,

the entrance to Moorcock’s house bears a perpendicular relationship to

the street address, the result of an L-shaped lot that dates to when the

legendary English writer bought the house in 1994 with his American

wife, Linda Steele.

Partially because it’s confusing and

partially because I’m an idiot, I practically circle the place before I

find the door. The cat does not look too impressed.

It’s fitting

because Moorcock, 71, is one of the preeminent fantasists of his age,

having given the world everything from the iconic anti-hero Elric to the

immortal/immoral anarcho-terrorist Jerry Cornelius, to the wretched and

completely unreliable Col. Pyat.

As the editor of the English literary magazine New Worlds,

Moorcock midwifed science fiction’s transition between the Golden Age

and the new wave, making a home for such avant-garde writers as J.G.

Ballard, Thomas Disch and Norman Spinrad.

It’s impossible to

imagine generations of writers without Moorcock, from Alan Moore to Neil

Gaiman to China Mieville. (Heck, it’s impossible to imagine something

like Dungeons and Dragons without Moorcock’s Eternal Champion books.)

He made records with Hawkwind and won acclaim for such mainstream novels as Mother London, which was shortlisted for the Whitbread Prize. A 2010 anthology of his nonfiction, Into the Media Web, spans fifty years, 300,000 words and 720 pages, and weighs 4.5 pounds.

Look

on his works, ye mighty, and, well, at least be a bit intimidated at

his productivity and his imagination. It really is something else.

But if you have no idea who the man is, his most recent book is not a bad introduction.

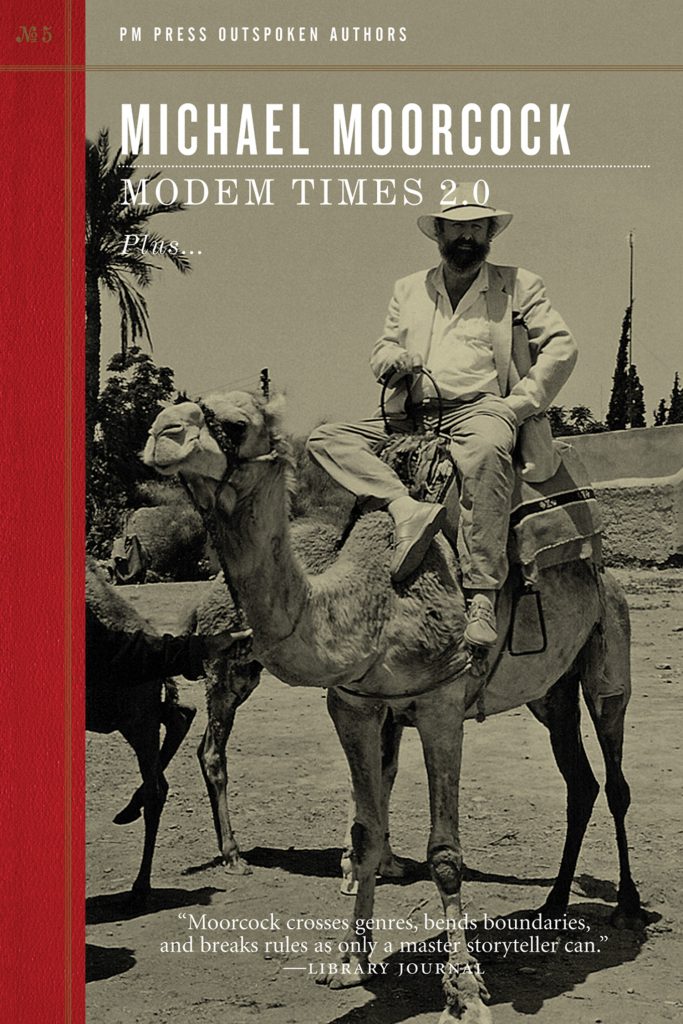

Modem Times 2.0

is an entry in PM Press’ “Outspoken Authors” series and comprises an

appropriately baffling and non-linear Jerry Cornelius short story

(slightly revised from a story published in 2008); the essay “My

Londons,” a clear-eyed reflection on Moorcock’s life in that most iconic

of cities; and an interview with Moorcock conducted by series editor

Terry Bisson. (You might know Bisson from his excellent

alternate-history novel Fire on the Mountain; if you don’t, you should.) PM Press also is slated to reissue Moorcock’s Pyat Quartet starting in March 2012.

Cornelius

isn’t Moorcock’s most famous character, but perhaps he is the most

flexible, which is saying something for a writer famous for leaving

himself an awful lot of room for multiple meanings (or no meaning at

all).

The blurring of high and low art, and a mix of science

fiction, fantasy and avant-garde literature, has been a through-line in

Moorcock’s singular career.

“The Cornelius stuff wasn’t published

as sci-fi in England,” Moorcock says. “One of the frustrating things

about America for me is the tendency to isolate anything that has any

pretensions to address a grown-up audience and start slotting it into a

special category, like calling an English TV version of ‘I, Claudius,’

‘Masterpiece Theatre.’ There’s a division between, let’s call them,

intellectuals and the public in this country that is so much greater

than it is in Europe. It’s much harder to find an ordinary, common

cultural level.”

Is Cornelius a hipper-than-thou secret agent,

indulging in every vice? Is he an adolescent fantasy? All of this and

more. Cornelius is where Moorcock’s head goes when events warrant.

“If

things in the world get too painful, I start to automatically default

into Jerry Cornelius,” Moorcock says. “For example, I’m writing a

Cornelius story right now that has to do with the various uprisings in

the Middle East, but it’s not set there, which is pretty typical for

that character. I try to find angles of attack that aren’t the normal

angles. He’s less a character than a literary device.”

Well,

that’s certainly true. The Cornelius books are less sci-fi than

experimental fiction—more in the tradition of Thomas Pynchon or William

S. Burroughs than, say, Isaac Asimov. Often made up of seemingly

disconnected paragraphs, they work as much by juxtaposition as anything

else.

“I don’t like to deal with the event head-on,” Moorcock

says. “If you don’t, it perhaps broadens the subject. Sometimes it

doesn’t work—this is an on-going experiment—but when it works, a

Cornelius story should be able to give a few different angles on world

events.”

Right now, Moorcock is enmeshed in The Whispering Swarm, the first book in the planned “Sanctuary of the White Friar” trilogy.

“I’m

not sure if I really should be working on trilogies at my age,”

Moorcock laughs, “but this one is essentially an autobiographical novel

with a very heavy fantasy element.”

Whispering Swarm is

about London, but a London with a key difference. “There was a part of

London called Alsatia that was a sanctuary for those who had broken the

law,” Moorcock says. Located between the River Thames and Fleet Street,

and including the Whitefriars monastery, Alsatia held the sanctuary

privilege (and a certain measure of lawlessness) for centuries before

being dissolved by Parliament in 1697.

It’s an extremely

attractive idea, and Moorcock imagines it has continued to the present.

But he adds that the book is autobiography, mostly. “I’m trying to look

at the ways I used escapism at crucial moments in my life, my two

previous marriages, for example,” he said. “Whether I used escape routes

and how I used them.”

There isn’t a publication date yet — “It

isn’t scheduled because I’m only a third of the way through the bastard”

— but may he live to finish it and a dozen more, on this Earth and

others.