By Len Wanner

The Crime of It All: At the Critical Edgeof Crime Fiction

September 2011

How would you describe yourself in a sentence?

A guy doing everything he can to make up for a lack of natural talent with pure pigheaded tenacity.

How would your best friend describe you in a sentence?

A guy who takes himself way too seriously.

Crime fiction is at its best when…

it takes crime seriously. Obviously not every book hits on every issue to do with crime, nor should they, but the best take their subject matter very seriously—even when they’re being funny about it. Also, when the art of fiction is at the forefront of the equation. There’s no reason great writing should be considered solely the domain of so-called literary fiction. Especially given how many great writers are writing crime fiction right now.

The worst literary vice is…

not doing everything within your power to write the best book you can at the time you’re writing it. I’ll put up with an awful lot from an author who you can tell is stretching their own powers. Who is doing everything they can to write at their very best. Others, the ones who’ve discovered a formula to sell books and are coasting on it, whether it be in the crime or literary genre, those are the ones I have zero interest in. I’d rather read the backs of cereal boxes.

The highest order a writer can aspire to is…

to be one of those that strike that perfect balance between artistry and just letting it all hang out on the page. Nothing gets me more excited than reading a great metaphor, a perfectly hewn sentence, or a brilliantly developed theme. Nothing. But, at the same time, I just can’t read fiction where there’s nothing at stake. It’s gotta come through that the book meant the whole world to the author. That they put absolutely everything they had into it.

Plot or character?

Character, easy. Character provides ninety percent of the movement I care about in a novel.

What’s your favourite word?

Lonesome, per Woody Guthrie. You can be lonesome for a job, for a little company, for a drink of whiskey, or even be high lonesome on a bender, but everybody’s lonesome for something. Self-help gurus will disagree, of course, but they’re lonesome for your money.

it takes crime seriously. Obviously not every book hits on every issue to do with crime, nor should they, but the best take their subject matter very seriously—even when they’re being funny about it. Also, when the art of fiction is at the forefront of the equation. There’s no reason great writing should be considered solely the domain of so-called literary fiction. Especially given how many great writers are writing crime fiction right now.

The worst literary vice is…

not doing everything within your power to write the best book you can at the time you’re writing it. I’ll put up with an awful lot from an author who you can tell is stretching their own powers. Who is doing everything they can to write at their very best. Others, the ones who’ve discovered a formula to sell books and are coasting on it, whether it be in the crime or literary genre, those are the ones I have zero interest in. I’d rather read the backs of cereal boxes.

The highest order a writer can aspire to is…

to be one of those that strike that perfect balance between artistry and just letting it all hang out on the page. Nothing gets me more excited than reading a great metaphor, a perfectly hewn sentence, or a brilliantly developed theme. Nothing. But, at the same time, I just can’t read fiction where there’s nothing at stake. It’s gotta come through that the book meant the whole world to the author. That they put absolutely everything they had into it.

Plot or character?

Character, easy. Character provides ninety percent of the movement I care about in a novel.

What’s your favourite word?

Lonesome, per Woody Guthrie. You can be lonesome for a job, for a little company, for a drink of whiskey, or even be high lonesome on a bender, but everybody’s lonesome for something. Self-help gurus will disagree, of course, but they’re lonesome for your money.

If you could remove one word from the parlance of our time, what would that be?

Redemption. Hate the word, hate the concept.

If you could remove one profession from the planet, which would that be?

Cops. I’ve never been in a situation that was improved by their presence, not one. And I don’t ever again need to play subservient to some twenty-five-year-old with a head full of Jason Statham movies and three hours a year of range time.

If you could remove one person from the planet, who would that be?

Toby Keith. Stopped by his restaurant last night and had an American Soldier burger with Freedom Fries, served by his Whiskey Girls. There was even a shopping section my wife wouldn’t let me visit, where I bet you could buy those stupid skinny cowboy hats. The only thing missing was a Toby Keith hair salon where you could get Toby Keith highlights.

Which fictional character is going to be shot come the literary revolution?

Henry Perowne from Ian McEwan’s Saturday. And, come to think, the rest of his upper-crust, whining family. I kept waiting for the whole thing to be some kind of joke. I was three-quarters of the way in before I finally realized there was no vicious satiric turn coming.

Which fictional character would you most like to meet in real life?

Ahab, about fifteen minutes after his dismasting.

What’s the best oneliner you’ve ever read or written?

“She would have been a good woman, if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life,” Flannery O’Connor. I’m about as far from Catholic as you can get, but that always seemed the perfect line to me.

An American, an Englishman and a Scotsman walk into a bar…

My guess is somebody’s getting fucked up.

Your ideal party of five is composed of…

Sticking to the living: Cormac McCarthy, Harry Crews, Slavoj Zizek, Noam Chomsky, and Emmylou Harris. I wouldn’t say a thing. Just curl up on Emmylou’s lap and try not to miss a word.

Which book other than your own do you wish you’d written?

Lately, Gilead by Marylinne Robinson or Tree of Smoke by Denis Johnson. Not because of what amazing books they are—though they are—but because if I could write them, then I could probably write anything.

Sum up your latest book in no more than 10 words:

Charlie and Ira Louvin. Booze, brutality, and blood harmony.

What’s the most amusing situation your writing has gotten you into?

At one point I had an entire notebook full of racial slurs for a book I was writing but never finished. And I got drunk at this Chicano bar in North Denver one night and left it on the table. Well, I couldn’t let it go—it was months worth of research from the factory I was working at—so I had to go back in and ask the bar tender if he’d seen it laying around. He smirked at me, reached down, and tossed it on the bar. And then when I asked him for a beer, he just shook his head. I exited, quietly and quickly.

If God exists, what will you say when you crash the pearly gates?

I thought you’d be bigger.

Who is your ideal reader?

There’s actually one guy who I always think of. His name was Tom and I worked with him on an assembly line for awhile. He was in his forties, just out of prison for credit card fraud, a big scar down his arm from a knife fight. He was this working-class Zen character, and as far as I could tell, he didn’t do nothing when he was off work but drink good whiskey and read. He’d read every book I’d ever heard of, and turned me on to dozens I hadn’t. He had no use for gentility and less for bullshit, but he loved literature like nothing else.

What appeal does crime fiction have for you?

I think of crime fiction as one of the last places you find the stuff I’m interested in. Class, race, the consequences of history, the necessity (or not) of violence, political and social corruption, the right of moral judgment, all those big things that don’t really get discussed anywhere else. There’s space to discuss those in crime fiction that doesn’t exist elsewhere.

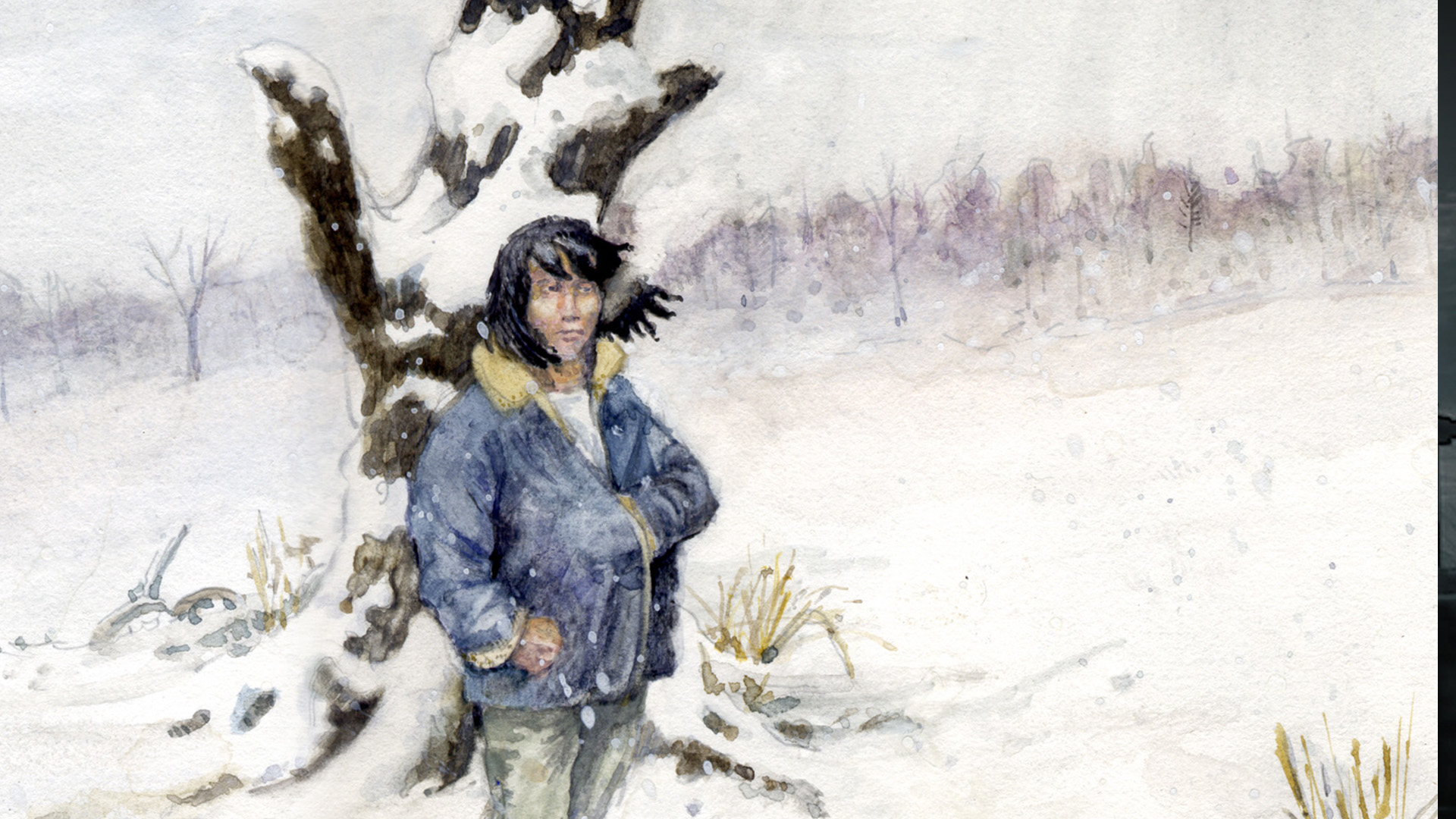

How did Pike come to you?

I had a vision of this hulking behemoth and a little girl. That was it. I didn’t know who he was, but I knew he’d lived a life of violence and would need it.

Who was he to you, and who is he to you now?

I finished the book about five years ago, and I think when I got done I had this impression of him as much cleaner and more pure than I do now. I mean, I knew he was flawed and I knew he wasn’t always right in his actions, but I saw him as almost Ahabian in his determination. Now I see him as much more compromised, much more uncomfortable. He’s more human to me now.

Where do his politics of violence sit vis à vis your own?

When I was beginning Pike I was thinking a lot about violence. I was reading Slotkin’s Regeneration Through Violence, William T. Vollmann’s seven-volume history of violence, Rising Up and Rising Down, and Ward Churchill’s Pacifism as Pathology. A lot of the questions I was coming up while reading those ended being played out in the book. Pike’s use of violence was a question for me. The way he thinks he can always determine who needs to be dealt with violently. The way he can make those judgments in an instant.

Don’t get me wrong, I’ve been around long enough to know that there are people you can only deal with violently. And I absolutely believe in the right of self-defense and to defend those you love. I’m about as big a proponent of gun rights as you’re likely to find. But Pike’s ability to delineate that line as easily as he does is troubling. And should be.

Crime writers are regularly charged with glorifying violence. Are those critics picking out isolated examples of prurience to hide their deeper aversion to an aesthetic of violence or what do you make of such criticism?

I get irritated at the charge, to begin with. Here in America, we live in a culture predicated on violence. The last century of expansion has been nothing but continual violence, and I won’t even go into the centuries that preceded it, with the so-called Indian Wars. (Wars that haven’t ended, as most of the folks I’ve met from, say, the Pine Ridge Indian reservation, will tell you in a minute.) The fact is, there hasn’t been a year in American history, ever, when we haven’t been engaged in combat somewhere. There’s no debate that we’re one of the most violent cultures on the planet. But it ain’t books, video games, or rap videos causing it—it’s the usual mix of politics, power, and greed.

But as to prurient violence, my answer’s easy: Shakespeare. The history of Western literature, whatever the hell that means, is the history of prurient violence. Deal with it. I consider myself a very minor player in a very proud tradition.

How do you approach a life, a character, and a scene that calls for violence?

I try and approach it from the vantage points of the characters involved. If a violent scene doesn’t reveal something about one or the other of the characters, I cut it. It’s the same as a sex scene, I guess, though I write less of those. Every act of violence is as individual as everything else a character does.

As a crime writer, what do phrases like ‘due process’ and ‘civil liberties’ mean to you?

Maybe it’s just where I’m at, but due process means nothing to me. Here, we’ve got more people in prison than any country in the history of the world. It’s an ongoing war of attrition on the poor. Due process doesn’t look to me like anything more than shoveling broke people into prison as fast as humanly possible.

As to civil liberties, or civil rights, there’s nothing I hold higher. At times in my life I’ve been a card-carrying member of the ACLU and the NRA. Any right you can keep to the people and away from government infringement, I’m for. And you maintain those rights by exercising them. Maybe it’s a result of living in a country where you can’t cross the street without it being legislated, but I’m of the opinion that the more freedom the people can withhold from their government, the better.

What are your thoughts on our current culture of fear and crime fiction’s dealings with it?

I think the culture of fear is entirely warranted in America. People have a right to be scared, especially working-class people. Hell, they oughtta be waking up in cold sweats every night. The fear isn’t always directed well, but not being able to feed your family, not being able to live a life of dignity, not being able to take care of those you love, not being able to ensure any kind of care in your old age, those are tangible realities. Our lives are being bargained away to make the already rich richer, and there’s absolutely no help coming, either from the government or their supposed watchdogs in the media.

They’re all owned by the same people.

That fear is one of the things crime fiction is uniquely able to address, and the best of it does. Thanks to writers like Charlie Stella, Daniel Woodrell, and Gary Phillips, crime fiction remains one of the few imaginative spaces in American discourse where class still exists. Speaking of fear, one of my greatest fears is that middle-class liberals will stop reading The Help and start reading crime fiction. Gentrification will come about ten seconds behind the first Oprah nod, and we’re all screwed then. They’ve already done it to me with Johnny Cash, I’m not sure I could take it again.

Do you think readers care one way or another when it comes to the above questions about an author’s politics?

The standard wisdom is that writers should keep their mouth shut about anything remotely controversial. And that’s fine for some, but for myself I would consider it profoundly chickenshit. Maybe I’ll wish otherwise further down the line, but right now I just feel incredibly blessed to be getting books published, and it’s very important to me that I do it the way I want to do it. Part of that definitely means not withholding my own point of view in hopes of achieving better sales figures.

Moreover, I really doubt readers care too much. I think about Flannery O’Connor, who was an avowed Catholic conservative, and Cormac McCarthy, who is described as a radical conservative. Those aren’t my political views by any stretch of the imagination, but they’re two of my favorite writers. I think readers understand how idiotic it would be to dismiss a writer because of their political views. Other writers, maybe that’s a different story.

How different is Pike’s world from our own?

That answer is two-fold, I guess. Back to Cormac McCarthy, he once wrote that “The ugly fact is books are made out of books,” and Pike is absolutely no exception. I can’t write except by writing to, from, and for other books. Whether or not I pulled it off, I was in large part consciously dealing with problems set out by other authors.

That said, I don’t think I made anything up as far as Pike’s world goes. It’s my interpretation of the world through Pike’s eyes, of course, but it’s also the world as I see it. I don’t think I could write a book that wasn’t. I hope to be able to someday, but I don’t have anywhere near the necessary tools yet.

Is Pike’s existential jaundice a symptom of our times or a solution to its problems?

It’s a kind of solution, I think. Maybe not the best one, but perhaps the only possible one, at least for people hardwired in certain ways. As the book opens, I see Pike as somebody who has seen people—himself included—at their absolute worst, and has since pared his life down to the essentials. Somebody who does everything he can to want less, need less, to keep his life as quiet and contained as it can be, given his own nature. That’s something I have a great deal of sympathy for, and I think the world could do with a lot more of it. I know I could.

Why did you touch on the controversy of a man becoming romantically involved with an underage girl?

The short answer is that that’s the direction they were moving in. I couldn’t see any other outcome. They’re two brokenhearted people doing the best they can, and it made sense to me that they would reach for each other. That’s what brokenhearted people do.

How do you sustain the high voltage charge inside Pike’s head throughout the writing of an entire novel?

Man, I really hope I sustained it. I worried constantly about it. If I did pull it off, it was just pure revision. Going over the manuscript time and time again, reworking sentences, reading it aloud, tweaking metaphors, doing everything I could to tighten it up. Just labor.

What does ‘noir’ mean to you?

I’ve never heard a better definition than Dennis Lehane’s line about noir being working class tragedy. That’s broad enough to encompass everything I care about, and restrictive enough to exclude what I don’t.

What’s a typical writing day for you?

Every day is a writing day, more or less. I just finished two book projects within a couple of weeks of each other and when I told my wife I was planning to take a month off before diving into the next, she just laughed at me. And she was right to. I lasted four days.

I usually get up early, before my wife and kids, write for awhile, go to the day job, write on breaks, come home, and after getting through dinner and evening activities, write or read after the kids are in bed. A couple times a week—as much as I can, though not as much as I should—I skip one of the writing sessions to take a walk. But then, most of my time walking is spent thinking about whatever project I’m working on. I live on the edge of Denver’s northside industrial wasteland, so there’s lots of inspiration there. And I’m not too far from the mountains, which is immensely helpful.

I do my best not to write on the weekends, to save that time for family, friends, and brown liquids. But it doesn’t usually work out that way. Luckily, I don’t really have any other hobbies besides shooting 3×5 cards. And with the price of ammunition these days, that’s not one I can indulge very much.

Take me through the major and, if you like, minor stages of your writing, from a novel’s inception to its completion. Anecdotes are welcome.

So far, they’ve all started in different ways. Pike started with an image. The one I just finished started as a framing device for another I’m about half done with, and that one started with the title. Then I’ve got an idea in mind for another that started from research I did a few years back in order to teach a series of classes on genocide and American Indians.

After I get the initial idea, my process is just flat stupid. I write a first draft. I hate it. I end up keeping some kernel out of it, and, if I’m lucky, fifty percent of the text. Then I rewrite that. And of the new material I usually end up keeping some new kernel and hopefully another fifty percent of the text. And I keep doing that until I’m satisfied enough to start real revision work. That process seems to take me a year, at least.

Revision is uglier. At first it’s big stuff. Adding new scenes, cutting others. Then I get down to sentences, themes, metaphors. And then back to adding and cutting scenes. This until I’m just exhausted, until I’m so sick of the thing that there’s just nothing else I can give the project. Then I’ve got no choice but to give up and call it done. That’s usually at least another year.

During that process I’m trying to keep most of my reading geared to the book. And trying to visit the places where I want to set scenes. With Pike, that meant walking all over Cincinnati, taking my infant daughter into some bars and alleys she had absolutely no business being in. I kept a Glock 9mm in her diaper bag, but never had any need for it. That’s one of the most fun parts for me, getting out and exploring places I probably shouldn’t be in. As a guy pushing middle-age, it’s a lot of fun to have an excuse to just hit the streets and explore.

I always think that there must be smarter writers who don’t need to do it this way. But I’m not one of them. It’s labor intensive, and it’s indefensibly dumb. Luckily, I love every phase of it, including revision. If I didn’t, there’s no way in hell I’d do it.

What are you working on right now?

I’m just getting back into the half-finished one I mentioned above. It’s a monster, set in Denver in the 1890s. A train-hopping, Panopticon, Pinkerton-killing, love-obsessed monster. I’m having to do things I’ve never had to do, and I’m really nervous about pulling it off. We shall see. It’s gotta be done, though, because the one I have planned after it will be a much more complicated beast.

Which books are you reading these days?

Right now almost all of my reading time is going to books by writers who will be participating in a panel I’m moderating at Bouchercon this year. Eoin Colfer, Sean Doolittle, Chris Ewan, Peter Spiegelman, and Keith Thomson. Which is a gas. When I get done with those, I’m looking forward to hitting new stuff by Sandra Ruttan, Barry Graham, Nigel Bird, and Stephen Graham Jones, which I have loaded on my e-reader. (Just broke down and got the cheap Kindle, and I’m absolutely sick at how much I love it.)

What do you know now that you wish you’d known when you started writing?

That it would take me 20 years of hard writing and reading before I came up with anything I considered worth publishing. But it’s probably best I didn’t know that.