by Roy Krøvel

Anarchist Studies 23

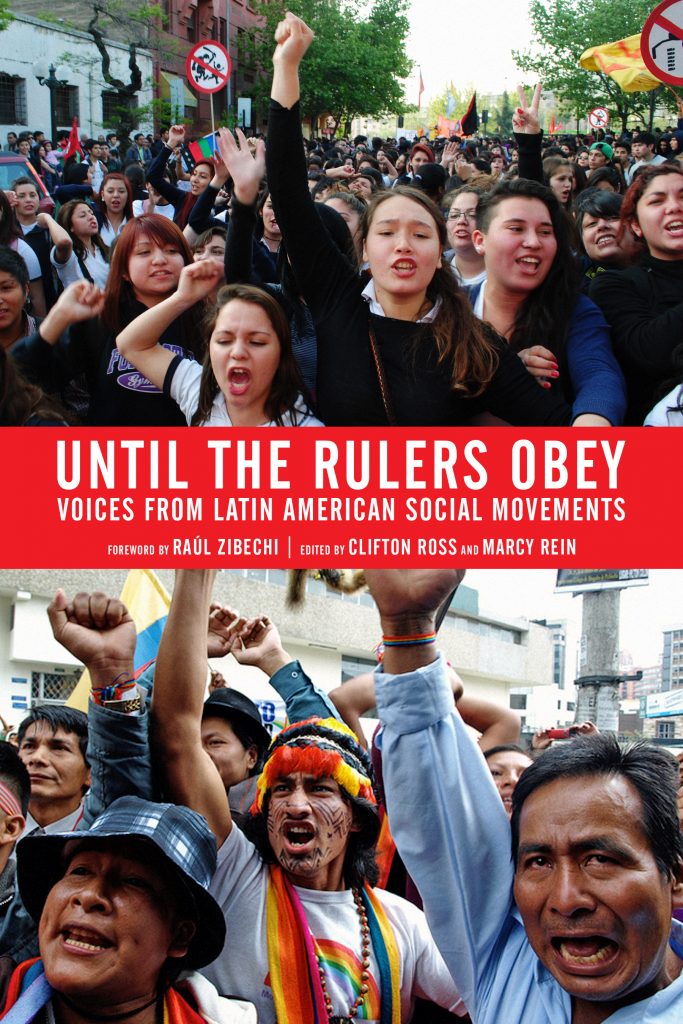

This book is a brilliant idea: the two editors (in addition to some friends) take us on a journey into ‘the magical world of Latin America’ (p xxviii). It is a trip starting in Mexico, moving into Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and Nicaragua before it continues to Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, Bolivia, Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay, Chile and Argentina. Along the way the authors introduce us to all sorts of social and political activists, including leaders of political parties of the left, environmentalists, indigenous activists, feminists and trade unionists.

This is a commendable effort for several reasons.

Understanding Latin America is in itself important as a wave of change has rolled through the area since the turn of the century. At the same time, Latin American social movements have undergone significant development and change over the last two or three decades, as Raul Zibechi describes in his foreword. Many of these new movements, for instance the Landless Movement of Brazil, the Zapatistas in Mexico, and various indigenous movements in the Andes, have come to play a vital role globally as they stimulate and inspire new social movements around the world.

No wonder Avi Lewis and Naomi Klein heap plaudits on the cover: ‘This is the book we have been waiting for’. Others call it a ‘wonderfully edited collection’. And still others ‘cannot imagine a more important and timely volume for scholars and activists who wish to understand the transformations that are sweeping the subconti- nent’ (William Robinson).

Until the Rulers Obey is at its best when the authors ponder the difficult relation- ship between the ‘new’ leftist regimes in Nicaragua, Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador, and social movements. Raul Zibechi has already reminded us that state policies tend to dissolve the self-organisation of those from below, turning many into clients of the regimes. The new presence of the state tends to ‘smother’ the movements (Zibechi, p xiv). Still, the editors do express some sympathy with the governments of the ‘Pink Tide’ in Latin America. However, the picture that seems to emerge from the interviews with activists is not very flattering for these governments, as the editors readily acknowledge. The interviews with activists living under the watchful eye of self-declared leftist regimes are a valuable contribution to our understanding of recent political processes in Latin America. Unfortunately, the volume does not reflect thoroughly on the profound implications of the conflicts between social movements and leftist regimes. In one instance, for example, the editors thank the ‘Sandinista police’ in a manner reminiscent of the camaraderie between solidarity activists and the Sandinista regime in the 1980s. In the chapters on Nicaragua, however, activists demonstrate how the current regime has succeeded in converting both the Sandinista party and the Nicaraguan state into a family affair, using the full repressive machinery of the state to exclude and marginalise opposition. It is difficult to understand why the Nicaraguan police should be celebrated for being ‘Sandinista’ under the current circumstances.

A more serious problem lies with the introductory chapters to each section. These are mostly old fashioned histories with very state-centred analyses of the political game between national political parties of left and right. This state-centred perspective is not very helpful for the reader who wishes to understand the emergence of new social movements from below. The focus on the political competition within states frames the interviews so that important features such as transnational aspects of environ- mental and indigenous movements become less salient than they should be.

In such a broad and ambitious undertaking, dealing with 15 countries and numerous organisations, it is of course almost impossible not to make the odd factual mistake.

Nonetheless, for readers of this journal the assertion that the Zapatistas (EZLN) emerged out of an encounter between ‘left Maoists and indigenous peoples’ might nevertheless be of particular interest (p xix). This claim is probably caused by a mix-up between the Maoist Linea Proletaria, headed by Adolfo Orive, an organisation that left Chiapas before the Zapatistas emerged, and the more Cuba oriented Fuerzas de Liberación Nacional (FLN), which later evolved into EZLN.

The editors are also too quick to label Augusto Sandino an ‘anarcho-syndicalist’ (p 116). While it is likely that Sandino encountered syndicalism on his journeys to Mexico, he remained a loyal supporter of the Nicaraguan Liberal Party until his death. Sandino welcomed support from anyone who could help in the struggle against the US supported regime, from liberals to Moscow communists, but he never seems to have contemplated the possi- bility that his movement could have had a leader other than himself.

These comments notwithstanding, this is a very sympathetic book which deserves to be read and discussed.

Back to Clifton Ross’s Author Page | Back to Marcy Rein’s Author Page