By Chris Steele

Counter Punch

December 24th, 2015

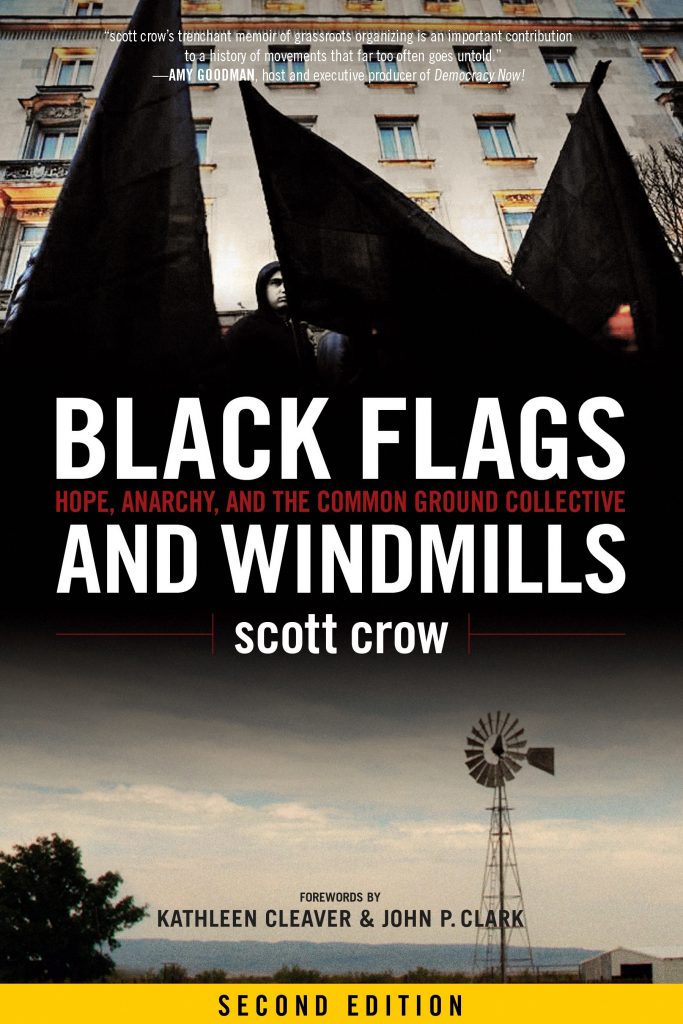

scott crow’s Black Flags and Windmills throws racist media sound bites of looting into the recycle bin of the internet and places the reader inside the battlefield of hope in New Orleans after the catastrophe of Hurricane Katrina in 2005. crow’s personal writing is not hampered down with stale homogenized statistics, instead he shares personal stories of struggle and tragedy that read more like a novel at times than a current affairs political memoir. The essence of crow’s book is inspired from Miguel de Cervantes work Don Quixote.

While Don Quixote saw thirty or forty “hulking giants” that he planned to fight, Sancho Panza explained that those weren’t “giants but windmills.” Whether one sees the state and racist ideology as giants or windmills, crow’s story explains the remedy is to organize in solidarity with others.

Author John P. Clarke and Kathleen Cleaver provide forwards for Black Flags and Windmills. Clarke highlights that with climate collapse, economic exploitation, and absolute poverty “we live in a state of emergency.” The significance of crow’s story is “being there for the community” explains Clarke, and the Common Ground Collective, which crow, Sharon Johnson, and Malik Rahim helped create is one based on community based mutual aid and solidarity.

Cleaver writes that Rahim “saw nineteen black people killed, and local authorities — black and white– refused to listen to his accounts.” “The bloody past of the toxic war to restore white supremacy after the collapse of the Confederacy,” writes Cleaver, “still nourishes violence in Louisiana — right there in Algiers where Common Ground had hundreds camping on their grounds.”

The Common Ground Collective (CGC) became the largest anarchist-influenced organization in modern U.S. history stating that, “With support from small organizations like ours, communities all over the region fought on many levels to have access to basic health care, to reopen their schools, to have decent jobs, to return to their homes and neighborhoods, and ultimately decide their own fates.”

Known for his political organizing and being under FBI surveillance, crow is described as a “puppetmaster involved in direct action,” according to an internal memo by the FBI’s Joint Terrorism Task Force. The FBI failed to mention that along with organizing, crow is also a talented writer as displayed in the following lines, “Smoke filled the air and my lungs with a haze as lonely helicopters creased the misty grey skies. Somehow, cranes and other waterfowl ignored everything around them and continued to hunt for fish on the swollen shores of the canal.”

crow explained that he came to New Orleans on a humanitarian mission but found himself in “the beginnings of a possible racial war.” Pointing out the conflict of this situation, crow explained how the majority of law enforcement and rescuers they met were white men, “while the majority of people in distress were a low-income and black population.” Hitting the essence of praxis (putting theory and reflection into practice), crow and Darby decided to leave the situation knowing that they were armed and ready to shoot in self-defense if need be but not worth it to “hurt someone to aid someone else.”

While back in Austin, crow received a call from his friend Malik Rahim who said, “‘…we got racist white vigilantes driving around in pick up trucks terrorizing black people on the street. It’s very serious. We need supplies and support.’” The call prompted crow and Darby to return to New Orleans, they went to the neighborhood of Algiers, where the city was in shambles as dead bodies laid on the ground.

To counter the white militias they established neighborhood security. The white militia was essentially deputized by the police silence allowing them to function. The militia had openly bragged about killing unarmed blacks and routinely patrolled neighborhoods and pointed guns at Malik yelling, “‘get ‘im.’” Their first security plan was to stand on Malik’s porch, armed. The white vigilantes came by the house in their truck shouting racist remarks, crow explained they nervously held their ground, the militia eventually left and the group became more empowered bringing the community together.

CGC was officially founded on September 5, 2005. Aside from security, the group sought to provide food, water, and medical attention while maintaining a horizontal, non-hierarchical power structure drawing inspiration from Zapatista and Black Panther Party principles. Defying the old anti-anarchist saying, “‘If there is no state, who will take out the garbage,’” the group went house to house helping people take their rotting garbage to a safe spot.

CGC set up their first medical clinic in Algiers at a mosque in the neighborhood. The first doctor they tried to get into the neighborhood was denied entry because he was black, crow wrote, “It was as if they had set up an apartheid system to determine who come into the area.

Unfortunately, his story was being replicated everywhere.” The Bay Area Radical Health Collective later helped CGC bringing holistic health care workers and an official doctor.

Told by state workers that CGC wasn’t even supposed to exist, crow explained, “The government’s agenda was simple; clear the area of people by force or starvation.” Discussing his privilege of being a white able-bodied male, crow wrote how he tossed away his guilt and used his privilege to access resources such as people, money, and media. crow discussed the hostility of police describing how helicopters often circled above them and that drive-bys in marked and unmarked black vehicles were frequent.

CGC also became a hub for grassroots media and radio. Volunteers brought UHF radios, microradio transmitters, Infoshop.org gave support, and the Indymedia movement “helped tell the deeper stories of New Orleans.” Another example of decentralized collaboration came from the Food Not Bombs (FNB) chapter from Hartford. FNB is a network of people who cook and give out vegetarian food for free to people in need. While the Red Cross would not go into the Seventh and Ninth Wards to help people who were stranded, FNB was there and gave out food.

All of CGC’s problems weren’t external, crow wrote of internal issues with patriarchy and oppression. In an effort to combat these issues, CGC drew up Guidelines of Respect (all communiques, documents, activities and programs are in the appendix), held antioppression workshops, and created women-only safe temporary shelters. On top of constructing a culture for their collective, the group typically worked for sixteen to eighteen hours a day.

To make matters worse, the category 5 Hurricane Rita soon descended on New Orleans intensifying Martial law and Shoot-to-kill orders. “The military were not there to protect and serve”, crow wrote, “they were there to do whatever they wanted with impunity.” CGC was threatened by two soldiers to shut down their aid operations, leading to a raid on their distribution center deeming it a “compound” and a “fortress.” With guns pointed and a helicopter blowing their supplies around, police yelled racial epithets as they rummaged through the group’s food, water, and medical supplies without a warrant. When the Red Cross finally arrived in Algiers, crow told of how the crowd of people in need were greeted with three fifty-foot trailers full of plastic utensils, napkins, and antiseptic cloths; no food or water!

To combat police hostility, CGC started a Copwatch group with cameras that were donated.

One incident involved a volunteer named Greg who was filming the police beat a young black man. Greg maintained a safe distance and was detained by police, where they made threats on his life saying they would “‘drop him in the river’ if Copwatch didn’t stop videotaping.”

Copwatch also discovered “Camp Greyhound,” which was a makeshift FEMA jail inside of a Greyhound bus station full of mostly black and Latino men. In addition, the facility lacked access to food and water; and people were “being held with no processing, without any documentation of their arrests, access to representation or means to communicate with anyone to where they were.”

As people started coming back to New Orleans nearly three months after Katrina, so did the developers. “For city officials,” crow writes, “poor people were a low priority in terms of reconnecting services; but some of their homes were of the highest priority from the coming demolitions.” crow explained that in some places “residential rents went from $400 to $1200 overnight.” As a way to fight back against illegal evictions and eminent domain, housing advocates used direct action and un-evicted people by helping them to move back into their homes.

A decade after Hurricane Katrina, bureaucrats and politicians continue to pat themselves on the back in the name of “progress,” while New Orleans is still devastated and has been struck with the bayonets of privatization. As pointed out by crow, cynicism and apathy are big obstacles in the U.S. but CGC is an example of how community and solidarity can combat tragedy. CGC is a reminder of the importance of telling your story so others can’t speak for you and misinterpret your message. John P. Clarke writes, “Common Ground is part of an enduring, age-old-counter-history, the history that writes itself against History.” Whether you see hulking giants or windmills, perception is everything and crow’s perception of solidarity and mutual aid are more needed than ever.

Chris Steele is a journalist. He can be reached at: [email protected].