For hundreds of years, he’s fought tax injustice, tyranny, and the seizure of the commons. Why we still need him today.

by Paul Buhle

and excerpt on YES!

February 15, 2012

“Man

has an insatiable longing for justice. In his soul he rebels against a

social order which denies it to him and whatever the world he lives in,

he accuses either that social order or the entire material universe of

injustice . . . And in addition he carries within himself the wish to

have what he cannot have—if only in the form of a fairy tale.”

—Eric

Hobsbawm, Bandits (1981)

In the late 1950s, a handful of

peaceniks protested mandatory ROTC on a major U.S. university campus by

carrying signs and wearing green buttons. Back when The Adventures of

Robin Hood was a giant hit on television, most everybody knew that green

was Robin Hood’s color and that Robin could not side with the king’s

soldiers or future soldiers of any empire. Five decades later, the lead

protagonist of a cult favorite American cable show, Leverage, announces

at the beginning of each episode: “The rich and the powerful take what

they want; we steal it back for you.”

A team of Robin Hoods faces off against a motley crew of capitalist clowns and banker jokers.

The game highlighted the possibilities of the Robin Hood tax as way of raising money for climate funds.

It’s

a fitting motto for heroes of the twenty-first century. Admittedly,

resistance to injustice has not as yet returned to the level of the

apprentices and craftsmen in Edinburgh, Scotland, who in 1561 chose to

come together “efter the auld wikid maner of Robene Hude”: they elected a

leader as “Lord of Inobedience” and stormed past the magistrates,

through the city gates, up to Castle Hill where they displayed their

unwillingness to accept current work-and-wage conditions. But as a

global society, we are clearly still thinking about the need for Robin

Hood.

After all, we live in something rapidly approaching a Robin

Hood era. The rich and powerful now command almost every corner of the

planet and, in order to maintain their control, threaten to despoil

every natural resource to the point of exhaustion. Meanwhile, billions

of people are impoverished below levels of decency maintained during

centuries of subsistence living. In this historical moment, the

organized forces of egalitarian resistance and even their ideologies

seem to be reduced to near nonexistence, or turned against themselves in

the name of supreme individualism. Robin’s Greenwood, the global

forest, is disappearing chunks at a time. Yet resistance to authority,

of one kind or another, continues, and, given worsening conditions, is

likely to increase.

Robin Hood lives on as a figure of tomorrow,

rather than just yesterday, in the streets of Cairo, Egypt, and Occupied

sites worldwide. Today’s Occupy Movement, in the U.S. and abroad, lifts

up Robin’s banner intuitively, reclaiming common space; but also

literally, as folks dress in Robin Hood outfits and caps to demonstrate

their sense of continuity for a better life.

A Taiwanese poster

for the latest big-screen (and hardly subversive) adaptation of the

Robin Hood story, directed by Ridley Scott, demonstrates the legend’s

ongoing global—and commercial—appeal.

No other medieval European

saga has had the staying power of Robin Hood; no other is wrapped up

simultaneously in class conflict (or something very much like class

conflict), the rights of citizenship, and defense of ecological systems

against devastation.

No wonder, then, that theater and poetry

seized the subject early on, and that modern communications, from

19th-century penny newspapers and “yellow back” cheap novels, to

modern-day comic books and assorted media have all had their Robin Hood

characters. No wonder that the early Robin films set records for lavish

production and box-office records for audience response. No wonder that

television productions of Robin have pressed issues of civil liberties

and that many of the later films, if distinctly mediocre, nevertheless

seem to refresh the subject, offering a source of summer holiday

distraction that never quite disguises darker themes within.

The Enclosure of the Commons: Circa Norman Conquest of 1066

John

Ball was no mythic figure, but a real leader of a major social

rebellion, assassinated as the rebellion was crushed in 1381. Little is

known about Ball otherwise: Like many an agitator, he was a lay preacher

with working men and women as his street audience.

Ball was once

thought to be the author of the totemic English poem of the time,

“Piers Plowman.” The authorship was otherwise, but the kinship is

striking. Piers Plowman’s complaint and demands, naturally placed in

theological terms during that time, nevertheless spoke to very real

contemporary

developments. These included a failed (but hugely

expensive) Crusade; the creation of the historic 1215 agreement between

king and aristocracy known as the Magna Carta; the rise of religious

dissent and in particular the spiritual rebels known as the Lollards;

not to mention famine and plague, among other cataclysmic events of the

time.

Behind these multiple crises, before the resulting

disruption and attempted revolution of 1381, lay centuries of European

village life, more specifically the creation of a sustainable ecosystem

in which the village had collectively survived invasions, diseases, and

all manner of earlier threats. Peter Linebaugh references Marc Bloch’s

description of “grey, gnarled, lowbrowed, knock-kneed, bowed, bent,

huge, strange, long-armed, deformed, hunchbacked, misshapen oakmen.” The

ancient oaks, Linebaugh says, were not the growth of “wildwood,” dating

back to the conditions formed by the Ice Age, but the consequence of a

planned and cultivated wooded pasture.

This was a reality, but

also a metaphor. The wooded pasture was nurtured by the villagers within

a common—that is, an area commonly held—with practices like

woodsmanship, so that the same stretches of land remained in use for

their wood value and for the grazing of domestic animals. Ash and elm

trees, capable of growing up from stumps, could be cut and used for

rakes, scythes, and firewood, while trees like apple and cherry, arising

out of root systems as “suckers,” grew rapidly out of reach of the

livestock to provide other resources. Wooded commons were often owned by

the local lord or merchant, but used by all. If the owner commanded the

soil and exacted a percentage of crops, grazing rights nevertheless

usually remained with commoners, and the trees belonged to neither.

Thus, as the cattle grazed, towns were physically organized through the

extensive use of wood in cottages, churches, and for the making of

bowls, tables, stools, and wheels.

The Norman Conquest in 1066, a

couple of centuries before Robin’s supposed time, did much to throw

these old rules of the forest into chaos. Changes brought new laws, new

populations (including French and Jewish), and even new animals for game

including certain kinds of deer not earlier seen in these lands. The

forest, as Linebaugh says, was now as much a legal as a physical

presence.

Other elements of change likewise pressing upon

villagers further complicated the picture. As Marxist scholar Rodney

Hilton explained in his classic, Bond Men Made Free: Medieval Peasant

Movements and the English Rising of 1381, serfdom expanded as the

centers of power grew stronger and more successfully exploited the

advancing sources of wealth, even as large numbers of “free tenants”

remained protected to some degree against the seizure of all surplus

through government and lordly dues and payments of one kind and another.

In many cases, farmers closer to markets were growing more prosperous,

but they were also the very farmers with dues-collectors closer at hand.

For

centuries ahead, the collective resistance across Europe, but perhaps

especially in England, coincided with the sense of better days somewhere

in the past, and this real and mythic memory continued to give ballast

to class resentments and radical hopes alike.

In all this, the

forest was a unique status symbol and a domain of kingship, both

symbolic and actual. Royalty needed wood for all the familiar reasons of

building and sustaining a palace life, as well as supporting the lives

of merchants and nobility in league with the king. For holidays, they

demanded sumptuous banquet food, including all manner of forest animal

life, as well as fish that swam in the forest’s rivers, and deer that

were forbidden to be trapped, killed, and eaten by anyone else.

Pickpockets, abundant at public events (including hangings), were more

likely to be shown mercy

than deer poachers, even with the animals in

evident abundance.

Cash was also necessary, in part to meet the

authorities’ demands upon the villages and forests to make possible the

latest forms of military escalation and associated expenses for the

king’s army. Royalty itself sold off forest privileges in order to pay

the cost of mounted knights with or without

armor. Not surprisingly,

then, one main demand in the Magna Carta was to take back the forests,

or at least limit their expropriation by the powerful.

The Magna Carta to the Ballads: 1215-1500

The

Magna Carta was hardly written by common people, and it hardly ended

oppression and exploitation. Like the later arrival of Protestantism, it

often contributed to new conditions for heightened exploitation. But

struggles against royalty and the established church offered symbols of

popular resistance and occasional victory, symbols also used in the

Robin Hood narratives. These helped make it seem possible to fight back,

in small and mainly local ways; they made it seem possible, sometimes,

to win back ancient rights that were in the process of being lost.

Thus

it happened that the main ingredients of the Robin story became

established in ballads, sung and written roughly between 1400 and 1500,

with a handful of basic narratives starring the now familiar characters.

From the beginning, their defense of villagers along with deer hunting,

archery contests, cunning disguises, daring rescues, and

crypto-romances were full of social and ecological implications, and

always rich in symbolism.

Robin Hood, the saga, emerged in

England at a time of bitter social conflict and was reshaped continually

by the modernizing forces of order and production. The medieval barons

who ordered playlets performed by singers and actors would not, of

course, wish Robin to be a social bandit—a romantic bandit certainly,

but not one with a social cause. Nor would most of the playwrights have

wished to pursue such themes.

The Robin Hood ballads could not,

however, have been created without the rebellious legends with their

anti-establishment emphasis casually reinforced in musical

entertainments as carnival-like games, and without the presence of the

very real social unrest sometimes taking place alongside

these

presumably innocent activities.

Robin in Chapbooks: Eighteenth Century Onward

From

the 18th century onward, readers began to encounter Robin in cheap

anthologies. These “chapbooks,” or crudely printed little volumes, could

run as long as eighty pages, but more often were twenty-four pages long

and included illustrations especially profuse in somewhat more pricey

editions.

But who bought them? Because broadsides, and then

chapbooks, sold more briskly in towns and cities than rural zones, their

audience was likely to be the urban lower classes, perhaps recent

migrants from the countryside seeking jobs and, for many, freedom from

the old bonds of rural life.

Sometimes, they would have been men

and women driven from the villages by the ongoing enclosures. These

readers in particular wanted entertainment but they also nurtured the

legacy of rebellion, and probably their own sense of nostalgia for the

beauty and quiet of the rural scene.

Ritson’s Robin Takes On “Titled Ruffian and Sainted Idiots”: 1795-1815

The pure glory of Robin spilled out into the work of Joseph Ritson’s Robin

Hood: A Collection of all the Ancient Poems, Songs and Ballads, now

extant, Relative to that Celebrated English Outlaw: To Which are Affixed

Historical Anecdotes of His Life, published first in 1795. Ritson

himself was a literary rebel, a wild enthusiast for the French

Revolution (and unlike some of England’s leading poets, never willing

afterward to repudiate its legacies), and a bitter critic of the Roman

Church as well as its English counterpart. Ritson was above all a

collector and an early archivist, and a highly intelligent one at that.

Ritson

established Robin’s qualities through an almost psychological study of

the available folkish documents: “Just, generous, benevolent, faithful

and believed or revered by his followers or adherents for his excellent

and amiable qualities.” Ritson also argued for the historical existence

of a nonfiction Robin Hood, an Earl of Huntingdon who “in a barbarous

age, and under a complicated tyranny, displayed a spirit of freedom and

independence which has endeared him to the common people” against all

the efforts of “titled ruffian and sainted idiots, to suppress” his true

story. This was quite a claim, and not one easily heard in an England

where defeat of the French and anxiety about “revolution” became

predominant sentiments. After 1815, as economic crisis merged with

imperial crisis, Ritson’s Robin Hood emerged as the accepted classic

version, along with folkloric inclusion of Robin stories in the Childe

Ballads collected and published during the last two decades of the 19th

century.

Quaker Robin Hits the United States: 1883

Howard Pyle’s Merry Adventures of Robin Hood of Great Renown in Nottinghamshire (1883)

was a genuine innovation, albeit in form more than content. Robin

material had only begun to appear in the United States at this time, and

Pyle had a growing reputation for his illustrated children’s books. It

has been suggested that the author’s native rural Delaware bore a

resemblance to Sherwood Forest, and his Quakerism contained a dissenting

sensibility (not, however, much of a pacifist limitation).

Williams Morris’s fascination with Pyle’s Merry Adventures

makes good sense because it was close to Morris’s own spirit, and in

line with the heavy praise that Pyle’s book received in the literary

circles of 1880s London. One can almost feel the Morrisian medievalism,

romantic poetry and all, in Pyle’s prose: “Five score or more good stout

yeomen joined themselves to him, and chose him to be their leader and

chief. Then they vowed that even as they themselves had been despoiled

they would despoil their oppressors, whether baron, abbot, knight, or

squire, and that from each they would take that which had been wrung

from the poor by unjust taxes, or land rents, or in wrongful fines . . .

to many a poor family, they came to praise Robin and his merry men, and

to tell many tales of him and of his doings in Sherwood Forest, for

they felt him to be one of themselves.”

Pyle wanted to send his

young readers into a place that only their imagination could carry them.

No small part of this was Pyle’s sense of nature lore: In the “merry

morn” of the forest, where “all the birds were singing blithely among

the leaves,” Robin finds adventure, and the natural setting is never far

from sight. It is also, or can be seen to be, all part of the grand

saga of England, Robin a necessary outlaw but a friend to the Good King

Richard, defender of the proper throne. This was schoolboy stuff, as

Pyle himself might have calculated, but schoolboy stuff of a superior

sort. The book has been in and out of print, mostly in print, for every

generation after its writing.

Douglas Fairbanks as Robin Hood gives Maid Marian a dagger in Robin Hood.

Big-Screen Robin, the Romantic Lead: 1922

Robin Hood as cinematic hero took the field at least twice in the 1910s, but in full force with Douglas Fairbanks in 1922. The Fairbanks version, true to the tale of the nobleman assisting the oppressed, but also pledging himself to King Richard, was also important in at least one other narrative respect: romance. Filmmakers had already grasped the significance of the female lead, especially for the sake of women in the movie audience. In this version, Marian is determinedly virginal and panic-stricken at her worse-than-death potential loss. Everything about Marian depends upon Robin: no innovation here. But there is more to be said, if only because of the film’s continuing cinematic importance. Robin Hood became and still remains a Hollywood phenomenon as the social rebel beloved of the ticket-buying masses.

Bandido: Robin as Freedom Fighter: 1936

“Joaquin,

the Mountain Robber” (ca. 1848). Artist’s portrayal of Joaquin Murieta.

Original at the California History Room, California State Library,

Sacramento, California.

Robin Hood of El Dorado (1936),

one of the most spectacular anti-racist films of a film era in which

these were rare and mostly limited to sympathetic treatment of

individual Indians. A highly fictionalized biography of Joaquin Murieta,

the famed social bandit who took to the hills to fight the invading

Anglo land-grabbers, finds the “yankees” looting and robbing the poor

Mexicans in mid-19th-century California. His encampment, a center of

merriment, dancing, and singing, as well as military training for a

guerilla army, was the best update of the Sherwood Forest guerillas in

modern cinema to the time. He first aims to rob the rich Mexicans who

have treated his own family so badly, and then learns that they, too,

have been expropriated. A daughter of that class takes up arms with him

as a lover and co-fighter, but as the guerillas plan to escape to Mexico

and safety, they are gunned down to the last member by ruthless,

murdering Anglo creeps.

Robin Under the Fascist Shadow: 1938

The

Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), costarring a heart-rending Olivia de

Havilland as Maid Marian, amplified a wealth-redistributionist Robin

Hood generally absent from the Fairbanks version. Leading man Errol

Flynn, reputed to be an early 1930s pro-Fascist (but always more

interested in chasing women and boozing), was soon to become the

anti-Fascist screen hero several times over. Before the end of his life

(at 50), Flynn pronounced himself, on prime-time television, to be a

drinking buddy of Fidel Castro’s.

Errol Flynn as Robin Hood and Olivia de Havilland as Maid Marian in The Adventures of Robin Hood.

Meanwhile,

playing Maid Marian, de Havilland was perfection. The noblewoman, at

first resentful and politically conservative, is won from her

aristocratic beliefs by Robin’s showing her the misery wrought by the

Norman occupiers. She follows her heart and her political growth step by

step into romance and partisanship. Very much her own person, this Maid

Marian is on her way toward a crypto-feminism of self-assertion.

What

else had made this iconic version a huge and lasting hit? Apart from

Robin and Marian, there is the notable camaraderie of the Merry Men, but

also notable is the stark evil of the authorities. The Sheriff of

Nottingham, as played by Basil Rathbone, means to wipe out all

opposition. He is a Fascist, whatever he happens to call himself. As

darkness swept over contemporary Europe, it was easy to identify those

like him in charge of the threat to decency, and their connections with

the powerful ruling groups of various nations.

Blacklisted: Robin at (Cold) War: 1955-1959

The

Adventures of Robin Hood (1955–59) was created and shot in Britain,

likely the only place that it could have been done. Its producer was

American Hannah Weinstein, a former theatrical lawyer (and organizer of

major events for the doomed Henry Wallace/Progressive Party campaign of

1948) who saw the writing on the wall and, like many of the victims of

the Hollywood blacklist, made up her mind to create a career abroad. In

Britain as in France, the blacklistees were welcomed as heroes,

notwithstanding the British government’s slavish acceptance of U.S.

foreign policies and military and intelligence operations across the

planet.

“The Adventures of Robin Hood” aired on Britain’s ITV

channel, a BBC competitor, and eventually attracted 32 million viewers

on both sides of the Atlantic.

Weinstein easily made contact with

blacklisted screenwriters living in New York, Hollywood, and Paris. The

most important, by a long stretch, was Ring Lardner, Jr., who, until

the witch hunt, had been regarded as one of the film colony’s brightest

young talent (as well as Katharine Hepburn’s personal favorite).

Lardner, Jr., and his longtime film collaborator Ian McLellan Hunter

were set to work with young script editor Albert Ruben in London,

devising a system—prompted by blacklistees’ inability to obtain

passports—by which he traded story ideas and scripts across the

Atlantic. This resulted in some of the best, wittiest, and most

political writing on television in an era of live drama and other

experimentation rarely seen again until film and cable competition drove

networks onward to risks political and sexual alike.

“The

Adventures of Robin Hood” set the small screen afire. It quickly

attracted 32 million viewers on both sides of the Atlantic. It also drew

upon the knowledge and insight of historical scholars—in this case

British scholars—offering examples of the use of existing laws in the

High Medieval Ages to protect commoners against the worst abuses that

aristocrats sought to hand out. With the careful oversight of Ruben, it

made for consistently clever, sometime hilarious viewing: The dialogue

was snappy and socially conscious (especially from Maid Marian) and the

bad guys were bad enough but also capable, now and then, of doing the

right thing, as when a forest fire or a psychopathic baron brought the

foes together in common cause. More often, Robin and his Men, joined by

Marian, typically protected an old woman accused of being a witch (i.e.,

the ongoing witch hunt in the United States); conducted a secret

mission to France and joined hands with the French Underground (shades

of anti-Nazi activities); provided aid to Friar Tuck, who was being a

people’s priest in resisting pope and sheriff; or frustrated the tax-man

or the hangman, for the nth time in the series.

It was also an

unforgettable slap in the face of the repressive 1950s. More, it

represented the struggle to get beyond them. Together, these shows

offered history as a way of learning, and as mass culture created with a

skimpy budget afterwards unimaginable.

Robin Today: Occupy the Meme

The

struggle for common space and decision-making—whether rural,

metropolitan, or global—can be traced back, in one part of the world, to

the changes forced upon royalty in the Magna Carta. They can carry us

forward to our opposition against privatization of formerly public goods

and space toward a society of a different—and more sustainable—kind.

Many millions of farms, urban neighborhoods, and software programs can

be or in many cases are already being operated on some basis of sharing.

The editors of An Architektur dub this process of struggle for

position “commoning.” Thus commoning is the opposite of the imperial

mode, right down to the struggle against dams being constructed on

rivers in or outside forests all around the world.

If the

“primitive accumulation” (Marx’s own phrase) of capitalism was effected

through enclosures—the privatization of previously common lands for the

purpose of successful wool production a couple of centuries after

Robin’s appearance—then he and the Merry Men (not forgetting Maid

Marian) had been seeking to nip the process in the bud. Marx erred,

writing in the middle of the 19th century, not by failing to see the

utter misery introduced to move primitive accumulation forward, but by

not seeing that primitive accumulation as a permanent process.

With so little of the planet not yet completely exploited, the process nevertheless accelerates. We need Robin more than ever.

We

need Robin because rebellion against deteriorating conditions is

inevitable. Without clear-headed Robins, however—without hundreds of

thousands or millions of them seeing clearly—the impulse to rebel will

surely be lost in internecine struggle and crime, organized and

unorganized, the mirror of class society at its destructive extreme. We

need them more now than ever before. No existing political model,

Marxist, Social Democratic, Leninist, anarchist, or other is suitable

for what lies ahead.

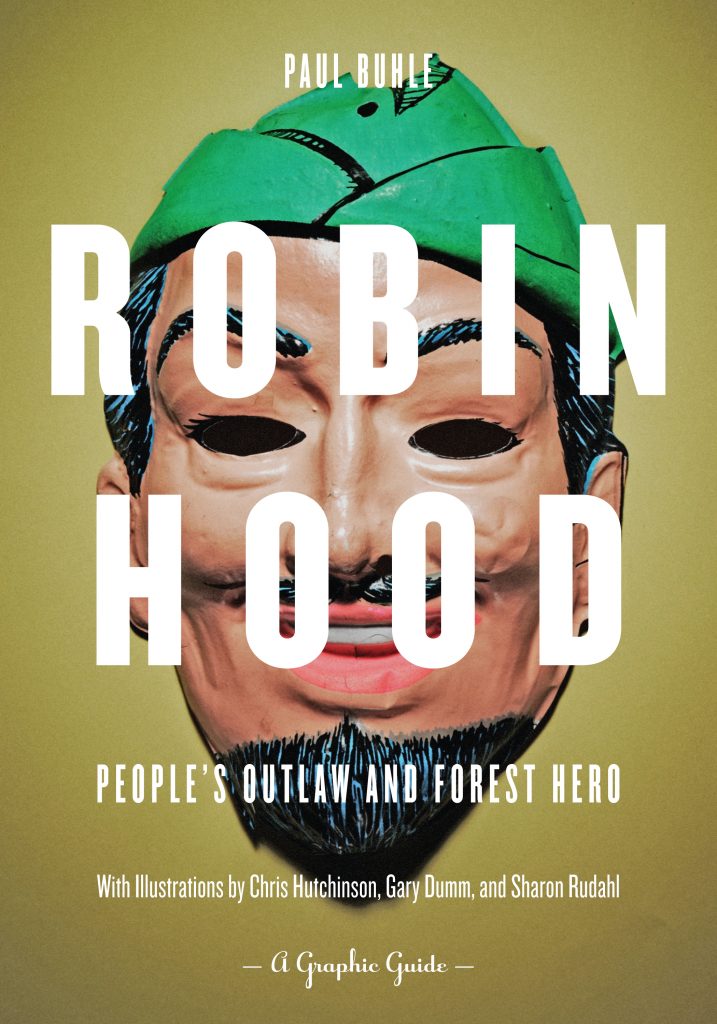

Paul Buhle adapted this article for YES! Magazine, a national, nonprofit media organization that fuses powerful ideas with practical actions, from his book Robin Hood: People’s Outlaw and Forest Hero (PM Press, 2011). Paul is the founder-editor of the new left journal Radical America and edits radical comic art books in Wisconsin.