by Jake Olzen

Waging NonViolence

November 9th, 2012

The aftermath of Hurricane Sandy has raised the question once again of whether post-disaster relief can help build organizations and networks that will create more resilient communities for the future. In trying to do so, East Coast activists and grassroots organizations — including the Occupy movement’s Occupy Sandy campaign — have been following in the footsteps of Common Ground Collective’s relief efforts in post-Katrina New Orleans. Even now, especially in the wake of Hurricane Isaac, the effects of organizing after Katrina are still being felt along the Gulf Coast.

Since Hurricane Katrina landed over seven years ago, residents of New Orleans and the surrounding communities have faced one environmental and humanitarian crisis after another. The BP Deepwater Horizon spill in 2010 severely damaged the Gulf ecosystem, leaving the public to bear the costs. Epidemics of poverty, homelessness, violence and incarceration continue to plague New Orleans. When Hurricane Isaac recently pounded the Gulf Coast with heavy rains that led to extensive flooding in August, it left in its wake another environmental disaster.

In nearby Braithwaite, La., the Stolthaven Chemical Facility has reported that as many as 191,000 gallons of chemicals — including toxics such as octene — may have leaked into surrounding waterways and communities. The Times-Picayune has documented the troubling inconsistencies in Stolthaven’s own reports to those of the Coast Guard and the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality regarding the contents of the spill. Residents were allowed to return to their homes — which have been severely damaged — for a few hours a day. With little support coming from government agencies, the continued experience of being forgotten and left to fend for themselves is par for the course for many New Orleans residents.

As people

assess the damage and rebuild their lives and homes, the Common Ground

Collective is one of the groups trying to help them do it. Common Ground

was first established in the days following Hurricane Katrina as a

community-organized response to the disaster when enough help did not

seem to be coming from government agencies. One of the Common Ground

Collective’s original co-founders, New Orleans resident and former Black

Panther Malik Rahim, wants to bring it back.

“There has never

been a collective like Common Ground Collective in the history of this

nation,” wrote Rahim in an email to me. “No other organization can say

[it has]

provided the multitude of services that we have provided while at the same time exposing the blatant acts that transformed Hurricane Katrina from a disaster into a national tragedy.”

In the aftermath of Katrina, residents of New Orleans’ Ninth Ward were abandoned by nearly every institution meant to help in case of an emergency. Local, state and federal governments turned a blind eye to the most vulnerable communities, leaving the area’s residents — mostly black — to fend for themselves against armed vigilantes and rogue law enforcement as they searched for food, shelter, clean water and medical care. The Department of Homeland Security hired Blackwater mercenaries to protect property. Detention camps — like the notorious “Camp Greyhound” — and an overwhelmed criminal justice system disrupted citizens’ lives for years to come as they sorted out case after case of mistaken identities and wrongful accusations. Rebecca Solnit, in her book about the communities that arise in the wake of disaster, A Paradise Built in Hell, called Katrina a “sociopolitical catastrophe.” This has been the general consensus.

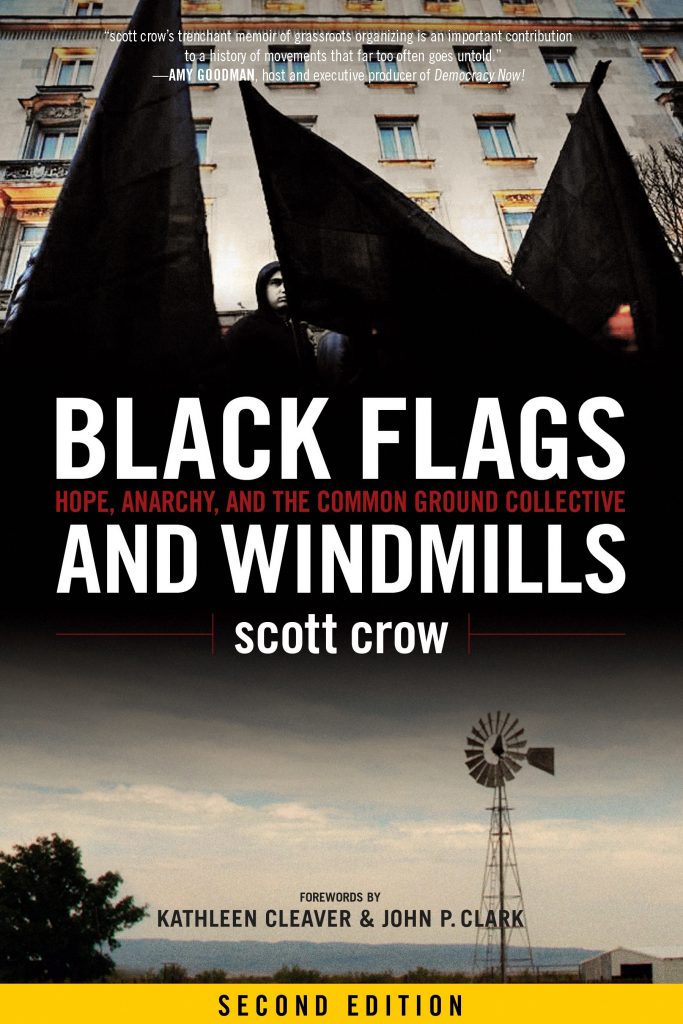

When official responses proved to have failed, a small group of volunteers — activists, DIYers, organizers — came together to do the work of rebuilding a community. The Common Ground Collective thus became the “largest anarchist-inspired organization in modern U.S. History,” according to co-founder scott crow in Black Flags and Windmills: Hope, Anarchy, and the Common Ground Collective. However, beginning in late 2006, alleged federal intervention played a role in tearing the collective apart.

Solidarity not charity

As many observers were openly criticizing the failure of the Bush administration and Mayor Ray Nagin to meet the needs of the Ninth Ward, it was an added shame that a rag-tag group of ordinary people were doing the relief that the government couldn’t. Contrary to media images and often-held assumptions that disasters create a vacuum for riot, rape and murder, the emergence of Common Ground after Katrina offered a glimpse of a better society than what the people of the Ninth Ward had before the storm. Young people flocked by the thousands to rebuild homes, cook food, clean up debris and repair homes. Health clinics, kitchens, work crews, cooperative housing and shared decision-making represented a viable alternative to the failed social order.

There were also hard lessons that are still being learned by those who tried to embody Common Ground’s mission of “solidarity not charity.” Cooperative and grassroots efforts like this are never supported by everyone, of course. Health department officials seized supplies and tried to shut down clinics and kitchens. Police harassed and arrested volunteers. In spite of all the fear and repression, millions of dollars of aid was raised and untold hours of time, talent and energy was given. But it didn’t last.

Naomi Klein, in her 2007 book The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism, details the ways in which advocates of neoliberal economic policies often take advantage of times of crisis and disaster, usually against the popular will. The period after Hurricane Katrina was a case in point; privatization was the response of the political class to every problem that arose.

The competing

visions for a future New Orleans clashed most openly in Common Ground’s

efforts to revitalize the Woodlands Apartment Complex in the

neighborhood of Algiers. After Katrina, rent skyrocketed and

homelessness was at an all-time high. The Woodlands had all but been

abandoned by its landlord when Common Ground stepped in to rehabilitate

the complex, implement rent control at pre-Katrina levels, organize a

tenants’ association and develop a workers’ cooperative to create jobs.

According to Malik Rahim, however, the Woodlands project came to a

grinding halt when the Woodlands’ owner (and famous New Orleans

restaurateur) Anthony Reginelli illegally raided Common Ground’s

Woodlands office.

On October 31, 2006, Reginelli, accompanied by

New Orleans police officers, seized — without warrant — leases,

contracts, computers and other things that were crucial to the ongoing

operations of the Woodlands, as well as the paperwork pertaining to

Common Ground’s upcoming purchase of the 13.5-acre campus from

Reginelli.

Common Ground had a verbal agreement with Reginelli to

buy the former public housing complex, for which Reginelli was

receiving federal aid subsidies even after Common Ground took over

management. Rahim later admitted that it was a mistake on Common

Ground’s part to enter into a “gentleman’s agreement” with Reginelli.

“There was a conspiracy to shut the collective down — literally destroy us,” believes Rahim.

Hundreds

of residents were eventually evicted from the Woodlands, dealing a

serious blow to the Common Ground Collective, which subsequently spun

off into an array of sometimes-feuding organizations, including Common

Ground Relief and the Common Ground Health Clinic, formed by anarchist

street medics.

“They didn’t want us with this much property and

350 units of coop housing — all done under the direction of a black

man,” said Rahim, who finally left left Common Ground Relief in 2010

because, in his words, “of turnover in organizational structure.”

Rahim

maintains that Brandon Darby — the controversial Common Ground

co-founder who later confessed to being an FBI informant — played a role

in sabotaging the Woodlands project.

“Brandon was the only one who knew where [those files] were,” said Rahim.

Rahim’s

2009 Freedom of Information Act request for FBI files detailing Darby’s

involvement with Common Ground were denied. The Center for

Constitutional Rights has filed a lawsuit on behalf of Rahim seeking the

release of the documents. Bill Quigley, one of Rahim’s lawyers and

former legal director for the center, called the government’s refusal to

turn over anything having to do with Brandon Darby “stonewalling.” The

case will be heard in federal court early next year.

With an eye

toward preventing this kind of infiltration from happening again in the

future, Lisa Fithian, another key organizer from Common Ground, has

written an exhaustive account — from personal experience — of Darby’s

activities. Darby’s own account of his involvement with Common Ground

and his work with state and federal authorities, inevitably, is more

complicated. Nonetheless, Darby’s presence — coupled with state and

corporate pressure bearing down on Common Ground — prevented the

collective from realizing its vision as an alternative to neoliberal

capitalism and its oppressive consequences.

Another hurricane, another crisis

As

Hurricane Isaac neared the Gulf Coast this past August, Rahim reached

out to Gary Roland — who had been one of the early organizers at Occupy

Wall Street and then spent time at Occupy NOLA in New Orleans — to help

coordinate post-hurricane relief. Roland, along with organizers from the

InterOccupy network and other Gulf Coast activist groups, started

Occupy Isaac Relief Distribution Network as a way to raise disaster

relief funds and coordinate aid projects.

But as soon as Occupy

Isaac had set up its community kitchen in the badly flooded city of

Phoenix — 20 miles downriver from Braithwaite in Plaquemines Parish —

word came that the whole area was contaminated due to the Stolthaven

spill. The kitchen closed and Occupy Isaac folded, directing what little

support it had raised to Common Ground Collective relief efforts such

as resurrecting a tool-lending library for home repair and mold

remediation. But Roland and Rahim still have a vision for doing more.

“In

the aftermath of Isaac, our focus is on building sanitary housing and

on re-kindling efforts to build a ‘solidarity hospital,’” said Rahim.

What he envisions would be a replacement for the now-defunct Charity

Hospital that used to serve New Orleans’ African-American community.

Rahim

— who has suffered health and financial difficulties in recent years —

says that the effects of state repression continue to linger, making it

difficult to realize these ambitions. But he thinks it may be possible

to try now. “I’ve made numerous attempts at re-organizing the

collective, but due to the spirits of distrust, caused by Darby and

others, the first few years were never right.”

Roland has a

background in urban development, and he is drawn to reviving the

original vision of the Woodlands — “a sustainable workers’ cooperative

in the community,” as he puts it, one that could cultivate farmland to

provide organic food and where people could direct a portion of their

rent to community projects.

Progress is slow, but Rahim just

started receiving his veterans’ pension, which he plans to use for

helping the collective establish a legal clinic to protect itself with

litigation. A few sizable donations have been made to the tool library,

and the Solidarity Hospital and the Common Ground Collective are in the

process of being established as formal nonprofit organizations for

fundraising purposes. These are small steps, but Rahim and his comrades

are continuing to build the resilience to weather the storms to come —

from nature, repression and poverty alike — and not give up on their

communities.