by Michael Novick

Anti-Racist Action LA

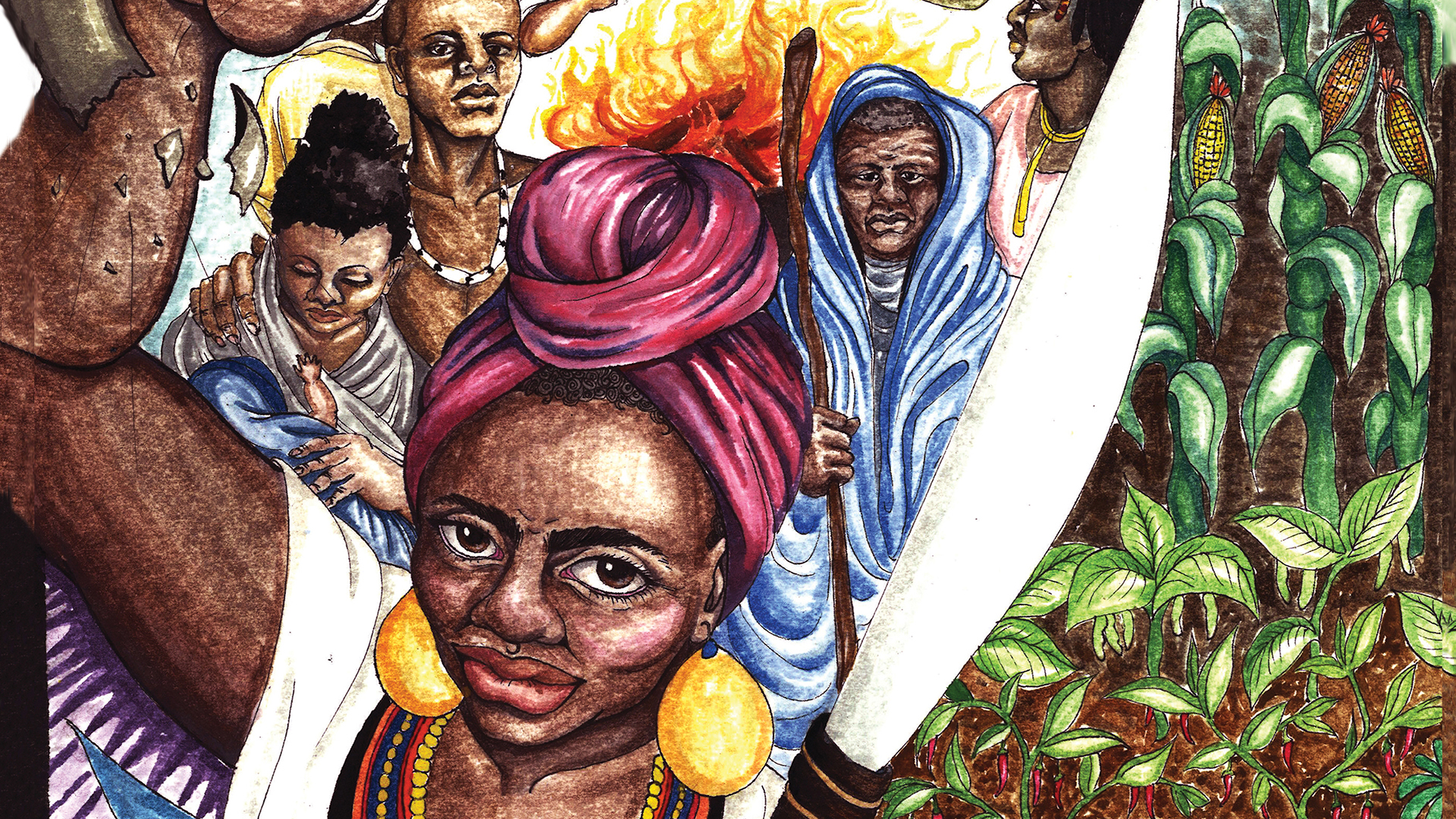

This fascinating book, based primarily on the writings of political prisoner Russell Maroon Shoats (#AF-3855, SCI Dallas, 1000 Follies Rd. Drawer K, Dallas PA 18612-0286), examines the history of slavery and liberation, particularly the form of resistance known as “maroons” — escapees from slavery, or territories liberated from slavery by rebellion, such as Haiti — in the US, the Caribbean and South America by applying the techniques of graphic novels to sometimes dense political tracts and analysis, increasing their appeal, accessibility and imbuing them with the spirit of a new Black arts movement as well as the cultural creativity and many-sidedness of the maroons themselves.

Sections include a short “Initiation” to the concept of the maroons, and pieces on “Slavery and Liberation”, Modern Maroons, and most challenging perhaps, Shoats’s manifesto “The Dragon or the Hydra?” counterposing centralized and hierarchical liberation movements or struggles, –the dragon — too often sold out by their own leadership, with the more decentralized, horizontal and variegated “maroon” struggles — the hydra, which grows many new heads when decapitated.

This is of course an issue in contention not only in the Black liberation movement, and among former Black Panthers and Black Liberation Army members like Shoats or their latter-day successors, but in many movements and contexts. Consider the contrast between the recent essentially anti-electoral presidential campaign of the Zapatista-influenced Marichuy and the much more traditional, and finally successful, campaign of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, who will take office as president of Mexico in December with a strong legislative and gubernatorial cadre of MORENA partisans who ran with him.

As the piece acknowledges, it may be faulty to identify all virtue with the autonomous communities of the Maroons. “In Jamaica, the British tried to make treaties with the maroons, to get them to stop welcoming escapees into their towns. Some maroons were even recruited to hunt down escaped slaves.” While Shoats see the decentralized structure of the maroons as an asset, so that “if one [leader] was bought off, others continued the struggle,” it seems clear that autonomy or decentralization in itself is not a safeguard against cooptation, nor do maroon zones or liberated areas necessarily threaten the entire edifice of empire and slavery.

A stronger element of the same piece, however, is the definition of a “mosaic” — a Movement of Oppressed Sectors Acting In Concert. Each group (women, New Afrikan and Pan-Afrikan peoples, Puerto Ricans, anarchists, Chican@s and Mexicans, Asians, LGBTQ people, etc) “retains its integrity, has its own culture and autonomy, but we are united because we share one economy, one ecology, and one planet. we must work together for our survival and our freedom.” This segues naturally into two final sections, “Modern Maroons” and an extensive bibliography of suggested additional readings of more traditional texts about maroons historically and currently and analyses of the system and of approaches to overturning and replacing it. The book has some of the appeal of “Addicted to War,” but is much more variegated in artistic styles and types of content, including a series of biographies and full page portraits of a large number of exemplars of the maroon spirit the book promotes, such as Haitians Ezili Dantor, Cecile Fatiman and Dutty Boukman, Queen Mother Moore, and the Black Liberation Army. Those introduced to the material thereby will find a wealth additional reading and study, as mentioned, in Saul’s bibliographic “Maroon Library,” (with thanks expressed to Matt Meyer and Richard Price).