by David Mandl

Comics Journal

January 10th, 2013

In the late 1970s and early 1980s a miraculous thing happened in left-wing circles: Anarchism, which was considered a quaint historical relic at best, rose from the grave to become the West’s most vibrant political movement. This was in part a response to the slow death of the ‘60s New Left, the corporatization of rock and roll, and the gradual slide toward a Reaganite/Thatcherite culture of greed in the US and UK: The most prominent left activists were now violent, authoritarian groups like the Weathermen and the Red Army Faction; arch-Yippie Jerry Rubin was about to throw in the towel and become the world’s best-known huckster for Yuppie careerism; and bland dreck like the Eagles and Fleetwood Mac dominated the radio airwaves. At the same time, the nominally anarchist punk movement was helping to spread dissatisfaction with the way things were, encouraging the young and the restless to indulge their creativity by (among other things) making their own music and art rather than consuming whatever a handful of entertainment companies decided to sell them.

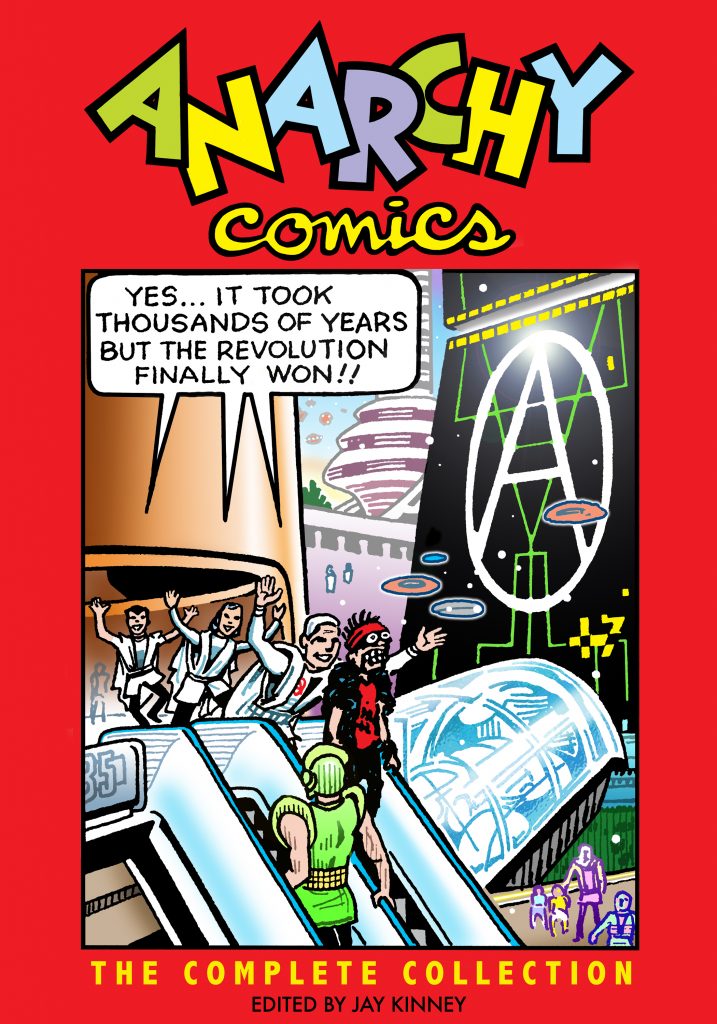

San Francisco, which had become a hotbed of punk activity, also happened to be home to a handful of anarchist study groups, and some members of the latter were underground-comic artists who saw their work garnering less rack space with the demise of (or legal crackdown on) head-shop culture. The convergence of all these phenomena inspired Bay Area cartoonist Jay Kinney—who had become increasingly interested in anarchist ideas while doing work for the lefty paper In These Times, and had collaborated with a pre-Zippy Bill Griffith on the underground comic Young Lust—to pitch the idea of an anarchist comic to Last Gasp, the most political of the local alternative publishers. Last Gasp said yes, Kinney’s sometime collaborator and fellow anarchist Paul Mavrides signed on as co-editor, and Anarchy Comics was the result.

In its nine years of existence (1978–1987) only four issues of Anarchy appeared, but it would be hard to overestimate the comic’s political and cultural importance even thirty years later. Kinney and Mavrides’s creation brought together an irreverent-bordering-on-nihilistic punk sensibility, serious (but never dry or pedantic) lessons in anarchist history, freshly illustrated texts by such infamous revolutionaries as Emma Goldman and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, and that favorite anarchist sport, satirical potshots at mainstream leftists.

Anarchists have always prided themselves on their internationalism—not surprising, since being anti-government is about the only thing all anarchists agree on—and Kinney took that attitude to heart, assembling a far-flung coterie of artists for his comic and emblazoning the catchphrase “International Anarchy!” (or “International Comix!”) on the front cover of every issue for good measure. In its lifetime Anarchy Comics featured contributors from the Netherlands, Germany, England, France, and the US, including Clifford Harper, Spain Rodriguez, the team of Yves Frémion and François Dupuy (aka “Épistolier and Volny”), Gary Panter, Ruby Ray, Gilbert Shelton, Donald Rooum, Melinda Gebbie, and more than twenty others. The majority of the work appearing in the comic was original, but Kinney also commissioned translations of several pieces not previously published in English—most notably the series “Liberty Through the Ages” by Épistolier and Volny.

Anarchy Comics was a nearly perfect blend of “capital-a” anarchism—that is, overtly political critiques of capitalism, patriarchy, and consumerism—and “small-a” anarchism—a generally anti-authority or anti-“normality” stance, not explicitly political. Its aesthetic was informed in about equal measures by punk, the Situationists (the influential ultra-left group at the center of the May ’68 rebellion in France), the underground-comic classics, and longstanding anarchist tradition. The Situationists’ mark could be seen in Kinney and Navrides’s use of détournement, the practice of re-purposing images from straight comics and advertisements by replacing the original captions with new, subversive ones. Punk showed up in the comic’s swipes at hippies and the middle-American nuclear family, and in its (at the time) novel and often bizarre graphic look.

All of the above came together in the Kinney and Mavrides’s opus “Kultur Dokuments,” in Anarchy Comics #2. The strip, drawn mostly in a cold, geometric, pictogram style, follows the Picto family as they morph from unremarkable residents of Dullsville, to members of a leftist cult handing out leaflets at the local asbestos factory, to a post-political group singing “Little Red Caboose” while toasting marshmallows on a burning Dullsville police car. Along the way they’ve altered their own graphic style (after being encouraged to “Drop your picto character-armor and go for the gusto!”) and, together with an assortment of cartoon pranksters, they’ve “hung the last bureaucrat with the guts of the last priest”—quoting a May ’68 slogan. Nested inside “Kultur Dokuments” is another entire comic, the brilliant and graphically meticulous Archie parody “Anarchie,” which the Pictos’ son reads to pass the time while locked in his room. Anarchie, resplendent in a punk hairdo and circle-A t-shirt, is thrown out of his house when he tells his hippie father, “You don’t even know you’re dead—you just keep walking around!” In response, Mr. Andrews shouts, “Meaningful dialogue in this relationship is impossible,” and, while booting Anarchie to the sidewalk, “Don’t come back till you mellow out!” Anarchie and his friends Moronica, Blondie, and Ludehead, en route to Mr. Lodge’s mansion (“Daddykins is throwing a posh ball tonight to celebrate his corporation foreclosing on some little country!”) get hassled by a bunch of passing hippies—drawn as the Furry Freak Brothers!—listening to “Uncle John’s Band” on the car stereo. The Deadheads hurl a can of beer at Anarchie’s head while chuckling “Hey punk! You look thirsty! Peace! Love! Ha Ha!” So much for “Be sure to wear some flowers in your hair.”

Among the more explicitly anarchist pieces appearing in Anarchy Comics

were illustrated historical strips about Durruti and the anarchist

presence in the Spanish Civil War (written and drawn by Spain), the

Yippies’ disruption of business at the New York Stock Exchange in 1968

(Épistolier and Volny), and the Paris Commune of 1871 (Spain again).

Épistolier and Volny also presented the story of the Kronstadt massacre,

wherein the Bolsheviks, consolidating their power in the

just-established Soviet Union (meet the new boss—same as the old boss),

slaughtered a group of anarchists who stubbornly clung to the original

libertarian ideals of the Russian Revolution. (Anarchists’ longstanding

animosity toward party-line Marxist-Leninists can in large part be

traced to this disaster.)

Other features that were meant to either educate anarchists on their proud history or counter common myths about what anarchism really is included Mavrides’s “Some Straight Talk About Anarchy,” Gebbie’s “Quotes from Red Emma [Goldman],” and Harper’s presentation of Proudhon’s “What Is Government?” Goldman’s illustrated quotes reveal a figure whose views on feminism and women’s rights were just as radical seventy years later: Woman’s “freedom, her independence, must come from and through herself…by asserting herself as a personality and not a sex commodity…by refusing the right to anyone over body…by refusing to bear children unless she wants them; by refusing to be a servant to GOD, the STATE, SOCIETY, the husband, the family, etc.” In “What Is Government,” an early document laying out the anarchist argument against centralized authority, Proudhon writes “Government is slavery. Its laws are cobwebs for the rich and chains of steel for the poor. To be governed is to be watched, inspected, spied on, regulated, indoctrinated, preached at, controlled, ruled…”

In “Some Straight Talk About Anarchy,” Mavrides blasts the 1984/Brave New World hybrid that the US had become by pointing out that life in the late twentieth century meant a choice between “Apocalyptic Babylon or Planetary Disneyland.” He mocks the non-progress made by labor in the previous forty years (“these days the right to peaceably assemble means quiet factories”) and espouses the self-evident but controversial view that people have the intelligence to organize themselves (“Your mind doesn’t need a government, does it?”). In a cartoon that appears on the inside cover of issue #1, widely reproduced ever since, Gerhard Seyfried juxtaposes the “popular misconception of a typical anarchist”—a sneering, black-robed terrorist holding a lit match to a bowling-ball-sized bomb—with “actual anarchists in real life”—a wholesome, garden-variety family of four. His point is a crucial one: Anarchists view anarchy as the natural, primordial state of things, and stress that most of our regular dealings with other people are anarchistic, in that we negotiate, cooperate, and help one another out of basic human kindness, free of outside coercion.

Less explicitly political, but more anarchic in the “chaos” sense is Gary Panter’s tongue-in-cheek and very punk “Awake, Purox, Awake,” a crudely drawn and pasted-up strip depicting two low-lifes who want to blow things up more or less for kicks. One of them asks, “What should we demolish today?” and then, after breakfast the next morning, declares, “Sunny day, full belly, makes me want to blow something up.” Exhibiting anarchists’ willingness to mock everything, even their own politics, is Mavrides and Kinney’s “No Exit,” in which they tweak both anarchists and ostensibly anarchist punk-rockers. The strip has a socially concerned but nihilistic singer (“Kill the Queen and kill the Pope / Kill the hippies who smoke dope”) traveling into the future to a time when the Revolution has finally won, and finding himself unable to deal with it. “Perhaps you’ll like the free autonomous bakers’ collective?” his hosts ask. “Here! Enjoy some 9-grain bread baked by unexploited labor!!” The punk takes one bite and spits it out: “Gak! Bleah!” He responds with equal horror to a blissed-out citizen who says, “I’m getting a telepathic message from the dolphins up on their L5 space colony,” drop-kicking her into a pool of sludge.

Other digs at the left’s party faithful include the illustration adorning the back cover of issue #1, “Exclusive on-the-spot sketch of mass anarchist demonstration in Tienanmen Square in Peking,” featuring hundreds of Chinese citizens in Mao suits brandishing little round bombs beneath a big “ANARCHY” sign. (Note: This was a decade before the famous Tienanmen Square protest of 1989.) The back cover of the following issue topped that, with a blasphemous Mavrides image (a poster actually available for purchase at the time) of Chairman Mao with huge Walter Keane eyes, and a wise-ass description sure to give any devoted Maoist a coronary: “Painted in oil and black velvet, this splendid example of true Proletarian Art combines stirring aesthetic skill with a sympathetic rendering of the late Chairman Mao’s wise, yet poignant face. Surely all revolutionaries who are concerned that Art should ‘serve the people’ will draw inspiration from this wonderful masterpiece and work hard to emulate its militance in every cultural area.”

Those two images, along with the rest of Anarchy’s front and back covers, are reproduced in their original form in a full-color section at the back of the assembled Anarchy Comics. It’s also interesting to note that the inside cover of each issue contains contact information (now obsolete, obviously) for a variety of anarchist groups and publications around the world. This marked what was probably the beginning of a movement that reached full flower a few years later, with anarchist groups sprouting up everywhere, anarchist zines being exchanged via international mail, and bigger and bigger contact lists of anarchist groups being circulated throughout the scene. (Some of the Bay Area people involved in Anarchy Comics also produced the massive International Blacklist of anti-authoritarian groups that appeared in the early ‘80s.)

Anarchy Comics represents the beginning of an important historical moment, when the philosophy and culture of anarchism were resuscitated after decades of widespread uninterest. It’s of its time, arguably, but with few exceptions it doesn’t seem at all dated today. It’s still as funny, irreverent, and illuminating as its editors intended. And it contains work from some of the best underground-comic artists of the late twentieth century, given free rein to snipe at authority to their heart’s content.