By Julian Wyllie

The Chronicle of Higher Education

April 5th, 2018

David Pilgrim says the first racist object he acquired, at 12 years old, was a salt shaker shaped like a dark-skinned woman in maid’s clothes. It was the late 1960s, in Mobile, Ala., a few years after Gov. George Wallace had blocked a doorway at the state’s flagship university, in Tuscaloosa, to try to prevent black students from enrolling there. The Chronicle of Higher EducationDavid Pilgrim says the first racist object he acquired, at 12 years old, was a salt shaker shaped like a dark-skinned woman in maid’s clothes. It was the late 1960s, in Mobile, Ala., a few years after Gov. George Wallace had blocked a doorway at the state’s flagship university, in Tuscaloosa, to try to prevent black students from enrolling there.

The America of Pilgrim’s childhood was “proudly segregated,” from the fountains to the libraries to the classrooms. But the “invasion,” as a local television reporter called it when Pilgrim was a child, was coming. Now in his 60s, Pilgrim was one of the millions who would take part in America’s civil-rights movement.

Pilgrim, the vice president for diversity and inclusion and a distinguished teacher of sociology at Ferris State University, has spent a half century amassing what may be the largest collection of racist memorabilia in the country. And he’s not done yet.

Founded in 2012, the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia has welcomed thousands of visitors into the basement of Ferris State’s library in Big Rapids, Mich. The museum has some 15,000 items in the collection, with about 10,000 on display, and a virtual space where people can explore the aisles from their desktops.

Pilgrim, who is black, never got over his fascination with racist objects. He realized in college that a scholar could also be an activist.

As a graduate student at Ohio State University, Pilgrim started thinking about the sacrifices people had made so that he and others could have better lives. That “great debt,” he says, made him want to dedicate his scholarship to something bigger than himself.

“We were the generation that was going to crash through that door, and we weren’t supposed to see that responsibility as a burden,” he says. “This is us paying homage to people who did the work, took the beatings. That’s a lot of pressure, but…” he trails, “I think I want to help people better understand the garbage, the bullshit that people created to hurt, to maim, and to expose it.”

So he began documenting the evidence.

Over the years, Pilgrim says, he became a hoarder of sorts, tucking his expanding collection of racist artifacts into free closets and the trunk of his car. He considered giving up at points, but he kept going because of his “ambivalent, weird-ass relationship” with what he’d found.

Sometimes he would spend all day on the road, scouring flea markets and the homes of other collectors, looking for racist items, and getting emotional at what he saw.

“If I found something, and found it at a good price, I felt like I’d had a good day,” he says. Other days he’d acquire nothing, but still value the legwork.

The most expensive item he ever obtained was a gift. A white student brought him a racist object that turned up in a relative’s basement: an 1896 print depicting a fisherman using a black child as alligator bait. Pilgrim says the disturbing image is valued around $10,000.

“They didn’t want any money for it,” he says. “I explained to them that it was an expensive piece, but they said they weren’t interested in selling it, they just wanted to get rid of it.”

A Chauffeur’s Hat

The idea of turning his personal collection into something bigger first came to Pilgrim while he was attending Jarvis Christian College, in Hawkins, Tex. O.C. Nix, professor at the historically black college, showed Pilgrim and his history classmates a chauffeur’s hat and asked what they thought it might have to do with Jim Crow. After a few incorrect guesses and puzzled faces, Pilgrim recalls, the professor told the students that the chauffeur’s hat was something that he used to wear while driving around rural Texas. A black man, Nix explained, even one who was educated and teaching at a college, couldn’t possibly have access to a nice car unless he was a driver for a white person — or so the thinking went. Without the hat, the professor said, he might have offended the wrong person.

The artifacts that Pilgrim had collected might mean something to someone other than himself, he thought, just like Nix’s hat. They could even be used as tools for teaching.

In the mid-1990s, Pilgrim decided he wanted to donate what was then 2,500 to 3,500 pieces to a museum. He considered other colleges, but only Ferris State would promise, at the very least, a small room to display the items. In 1996 the first of Pilgrim’s objects were moved to the university. As the collection grew in popularity and scope, grants and other funds became available to support its curation, display, and expansion. Today the museum is housed in the basement of Ferris State University’s Library for Information, Technology and Education.

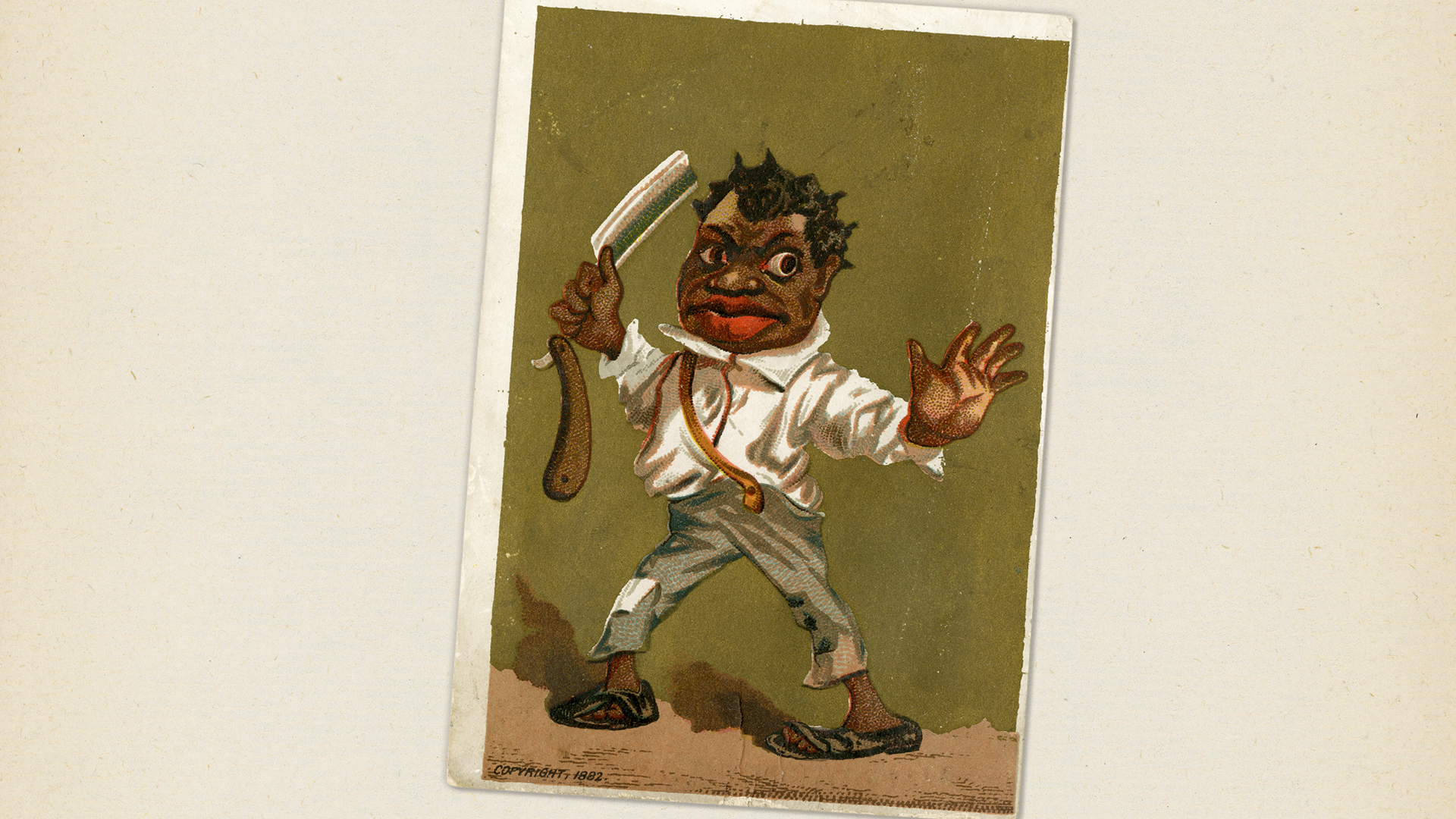

The collection of minstrel-show pamphlets, toy dolls, ashtrays depicting racist caricatures, and other items is worth millions of dollars, Pilgrim estimates, but its greatest value is the education it provides to visitors.

“It can be overwhelming,” Pilgrim says, but the mission is simple: “We use intolerance to teach tolerance.”

A Museum’s Momentum

John Thorp, a social-sciences professor who was instrumental in finding a home for the collection at Ferris State, says it took some time for people to warm to the idea. He notes that William A. Sederburg, who was president from 1994 to 2003, grew more supportive of the museum once he saw that it was gaining traction online and being featured in publications like the Detroit Free Press.

“My phone started ringing off the hook,” Thorp says. “Now people in the Detroit area wanted to see it — justice groups, church groups, school groups. We were off and running.”

Thorp, who retired in 2008, recalled a moment that illuminated the museum’s impact. He had a social-work class convene there one evening, and one student had brought along her kindergarten-age daughter. “The child didn’t really do much more than wander around,” Thorp recalls. The next day the student stopped by his office with a pair of bobblehead dolls that resembled black caricatures. She said the toys had caught her daughter’s eye on a shelf at Walmart. “Mommy,” the girl said, “this should be in the Jim Crow Museum!”

“When you get a 5- or 6-year-old who recognizes what’s going on,” Thorp said, “you know you’ve done something right.”

The collection has grown far beyond Pilgrim’s personal contributions. In February, Ferris State acquired the fine-art photographer David Levinthal’s “Blackface” Polaroids. The series features photos of toys and dolls that reflect racist attitudes about African- Americans, Pilgrim says. The university also received Levinthal’s “Barbie” and “Mein Kampf” series.

The goal is not to shock visitors, Pilgrim says. The museum indicts racists, not victims, and the point is to remind people that the truths of the past are often painful. “It’s a well- thought-out history lesson,” he says. Pilgrim says many visitors walk into the museum and wind up “paralyzed and transfixed” by the images. He’s seen people of all races cry, not in heaving sobs, but in single streams of tears, moved by what they have seen.

When white people cry, Pilgrim speculates, they may be realizing how particular society has been in oppressing some while giving others privilege. “Racial healing follows sincere contrition,” he says.

Pilgrim says it’s no surprise that the museum — and others, like the National Museum of African American History and Culture, in Washington, D.C., and the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center, in Cincinnati — has gained more attention with the current state of politics.

Business is booming. “Today, we are receiving five-, six-, seven-hundred objects a year through donations,” Pilgrim says, “and many of those are duplicates of objects that we currently have.”

The museum will have to become more selective, Pilgrim says, to make room for contemporary contributions. “One of the best decisions we ever made was to not limit the collection to the Jim Crow era,” he says.

“When there’s a race-based incident that occurs in the U.S. anywhere, if it gets national attention, there will be two- and three-dimensional objects made about it.” For example, after the 2012 shooting death of Trayvon Martin in Florida, someone produced targets bearing Martin’s image.

Pilgrim says he’s come across similar objects caricaturing Barack Obama, America’s first black president, as “apelike” or as a “witch doctor.”

“We didn’t have internet memes years and years ago, but now there’s all these memes,” he says, “and those don’t just stay as memes. They end up on T-shirts and posters.”

The museum is collecting such items not as a shrine to racism, Pilgrim emphasizes, but as an archive of America’s tragic past — and its present.

One item visitors won’t see in the museum is the “mammy” salt shaker he found so many years ago. On the day that Pilgrim bought it, in front of the white clerk, he abruptly smashed it to pieces.

“It was not a political act,” Pilgrim says. “I simply hated it, if you can hate an object.”