By Michael Kline

wvgazette.com

November 30, 2011

CHARLESTON, W.Va. —I

am amazed after visiting the State Museum at the Culture Center for the

first time since its $17 million facelift. As a taxpayer, an oral

historian and a former employee at the Department of Culture and

History, I was curious about how a state exhibit on coal mining might

read, or sound, in a state as friendly to coal as ours.

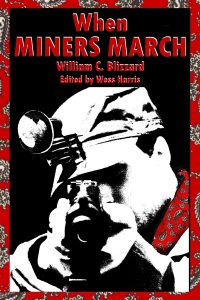

I went with my friend Wess Harris, a former coal miner and scrutinizer of public information—or lack of it—related

to the story of coal mining. Harris is a devoted member of the United

Mine Workers and passionately committed to public education on

rank-and-file labor history, especially the Battle of Blair Mountain. He

facilitated publication of When Miners March by W.C. Blizzard, son of the legendary Bill Blizzard, leader of the march.

Harris agreed to give me a “Truth Tour” of the coal exhibit, which he offers to any interested individual or group.

But

before we could get to the coal hall in the museum we had to pass a

panel on slavery which was so vapid, inaccurate and poorly written that I

am embarrassed for the department, embarrassed for school children who

wander disinterestedly past these inconclusive interpretations of the

darker chapters of our state’s past. I saw no evidence of museum staff

on hand to help students focus and no “hooks” in the exhibit panels to

catch the imaginations of younger visitors.

Further down a

hallway we found the coal exhibit characterized by static text and

photos. The texts, in addition to being full of inaccuracies, are

written with drab, ethically starved, yet loaded language with a

dismissive, pro-industry tone. The overall sense seems to be that,

although there have been difficulties over the years, especially the

violence initiated by “ardently socialist” rank-and-file miners, that

things had generally worked out over the long run for the coal industry,

whatever the social and environmental costs.

To refer to leaders

of the revered Redneck Army of West Virginia coal miners who fought at

Blair Mountain as ardent radical socialists is a real stretcher. It

betrays a class bias unbecoming to a public history enterprise. Nowhere,

in the spirit of a balanced presentation, does the exhibit refer to

coal operators as “boarish capitalists” who, like wild boars in the

wood, eat your meat and suck your blood. So why drag out old socialist

labels to pin on honest working people struggling for safe working

conditions and decent pay?

Throughout the exhibit, recorded

narrations play on speakers hanging from the ceiling. The speakers are

not properly engineered so as to be heard in a small space in front of a

particular panel. Instead divergent voices echo around the hall in a

cacophony of competing sounds unintelligible to my seventy-one year-old

ears. It’s little wonder that the dozens of bored, cooped-up

fourth-graders wandering the passageways were out of control, giggling

and shouting. Probably just as well. Why fall prey so young to publicly

funded propaganda in a state-supported and designed museum representing

the interests of, and featuring narratives approved by, Big Coal?

In

a little corner supposedly devoted to Blair Mountain is a glass case

showing off a machine gun on a tripod like ones Logan County Sheriff Don

Chafin and his 300 “deputies” used against advancing miners in late

August of 1921. On the wall behind the machine gun was a large photo of

the sheriff, with a lengthy text. “Now we’re getting somewhere,” I

thought. But the text was lit from above with tiny lights insufficient

to illuminate the print, and try as I might, I could make nothing of it.

I’ve

heard it said of Sheriff Chafin that he was mean enough to kick sick

chickens in a creek. He’s the kind of character who, if vividly

portrayed, could galvanize the interest of fourth- and eighth-graders,

as well as the rest of us. Like Wheeling’s Big Bill Lias, who ran

gambling and prostitution houses and Wheeling Island’s racetrack for

thirty years before he was jailed for tax evasion, Chafin’s pathological

brutality and intimidation were compelling.

So there we are

standing in front of the Chafin panel, and I’m in a sweat to see what it

says, but unable to decipher it in the dim light. “Do you suppose they

don’t really want us to read it?” I asked Harris.

“What do you think?” he retorted dryly.

Back

in the parking lot, I asked Harris how he thought the department had

managed to miss the mark by such a wide margin, given all of the

resources available, both financial— $17 million—and

historical: a rich diversity of primary sources. Then Harris produced a

photograph he took of the commissioner’s parking spot. It shows a large

dark SUV with a “Friends of Coal” sticker on the bumper. “That’s how,”

he said.

Kline, of Elkins, is a former member of the Goldenseal staff