New Book Surveys Oaxaca Uprising to Teach Rebellion

By Hans Bennett

Upside Down World

“I am 77-years-old. I have two children, eight grandchildren, and six great-grandchildren…My children are scared for me. It’s just that they love me. Everyone loves the little old granny, the mother hen of all those eggs. They say ‘They’re going to send someone to kill you. They’ll put a bullet through you.’ But I tell them, ‘I don’t care if it’s two bullets.’ I’ve become fearless like that. God gave me life and He will take it away when it is His will. If I get killed, I’ll be remembered as the old lady who fought the good fight, a heroine, even, who worked for peace…Hasta la victoria siempre. That’s what I believe,”says Marinita, a lifetime resident of Oaxaca, Mexico. Marinita was one of the many participants in the 2006 Oaxaca rebellion, whose first-hand account is featured in the new book released by PM Press, titled Teaching Rebellion: Stories from the Grassroots Mobilization in Oaxaca.

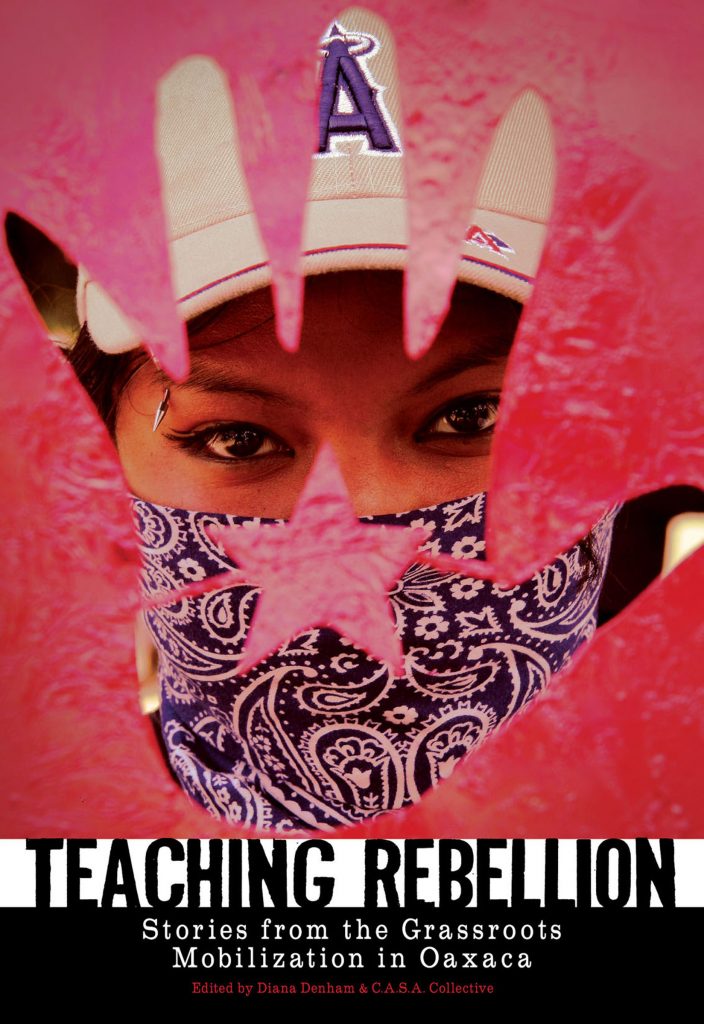

Teaching Rebellion does just that: it teaches us why the 2006 rebellion in Oaxaca, Mexico was so impressive, and is something we can all learn from. Edited by Diana Denham and the CASA Collective, Teaching Rebellion provides an overview of the uprising in Oaxaca. It also gives numerous first-hand interviews from participants, including long-time organizers, teachers, students, housewives, religious leaders, union members, schoolchildren, indigenous community activists, artists and journalists. The diverse interviews allow some of those who led themselves in rebellion to also speak for themselves. Political art is featured throughout the book alongside excellent photographs from the uprising.

The introduction, by Diana Denham, Patrick Lincoln, and Chris Thomas, provides an overview of the rebellion to contextualize the participants’ accounts. The story of the 2006 rebellion begins with a teachers’ strike and sit-in that occupied over fifty blocks in the center of Oaxaca City, initiated on May 22, 2006, by the historically active Section 22 of the National Education Workers Union. When the government failed to respond to the teachers’ demands for more educational resources and better working conditions, thousands took to the streets demanding a trial for the hated State Governor Ulises Ruiz Ortiz, of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), believed to have gained office in 2004 through electoral fraud. Five days later, 120,000-200,000 marched and held a popular trial for Governor Ruiz. Yet, the major rebellion was still to come.

On June 14, the police used teargas, firearms, and helicopters to brutally attack both the teachers’ sit-in at the city’s center and the union’s radio station—destroying their equipment and brutalizing the radio operators. This violent attack, meant to stifle the people’s resistance, backfired when the city rose in defense of the teachers. Transmission was taken up by Radio Universidad (at Universidad Autónoma Benito Juárez de Oaxaca) and thousands of supporters helped the union retake the city center that day. Two days later, 500,000 people marched through the city demanding that the federal government remove Governor Ruiz from office.

The next day, the Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca (APPO) was formed, eventually comprising over 300 unions, social organizations, indigenous communities, collectives, neighborhoods and student groups. The APPO’s autonomous, non-hierarchical approach in Oaxaca was “a new and original approach to political organizing,” Teaching Rebellion explains, but “it also drew from forms of indigenous self-governance, known as usos and costumbres. The APPO, an assembly by name, emphasizes the input of a diverse body of people who discuss issues and make decisions collectively; similarly, in many indigenous communities in Oaxaca, the assembly is the basis for communal governance. The customs of guelaguetza (which actually refers to reciprocity or ‘the gift of giving’) and tequio (collective, unpaid work for the benefit of the community) are the two traditions most deeply engrained in Oaxacan culture that literally fed the movement.”

With the June 14 police attack, the 2006 Oaxaca rebellion had begun. Teaching Rebellion continues:

“[I]n addition to responding to a police attack on striking teachers or a particularly repressive governor, the movement that surfaced in Oaxaca took over and ran an entire city for six months starting in June 2006. Government officials fled, police weren’t present to maintain even the semblance of responding to social harm, and many of the government institutions and services that we depend on daily were shut down. Without relying on centralized organization, neighborhoods managed everything from public safety (crime rates actually went down dramatically during the course of the six months) to food distribution and transportation. People across the state began to question the established line of western thinking that says communities can’t survive, much less thrive, without the intervention of a separate hierarchy caring for its needs. Oaxaca sent a compelling message to the world in 2006: the power we need is in our hands.”

The book’s introduction elaborates that after the June uprising, “no uniformed police were seen for months in the city of Oaxaca, but paramilitary forces terrorized public spaces occupied by protesters. These death squads, including many plainclothes police officers, sped through the city in unmarked vehicles, shooting at neighbors gathered at the barricades,” which were constructed around the city in defense against death squads and state repression. State repression began to escalate while negotiations were taking place between the APPO and the government, which only made the community more distrustful of the government. On October 28, 2006, over 4,500 federal police troops were sent to Oaxaca, attacking the barricades and retaking the historic city center where they set up a military base that was maintained until mid-December.

On November 2, the police attacked the university campus, home to Radio Universidad, but “in what turned into a seven-hour battle, neighbors, parents, students, and other civilians took to the streets to defend the campus with stones and firecrackers, eventually managing to surround the police and force their retreat.” In another major conflict that month, on November 25, “thousands of protesters marched into the city center and formed a ring around the occupying federal police forces. After a well-planned police attack, several hours of chaos and violence ensued, leaving nearly forty buildings ablaze. Hundreds were beaten, tortured, and arrested that day, and many movement activists and sympathizers not arrested were forced underground.”

This final repression essentially ended the community’s occupation and control of Oaxaca City, but,Teaching Rebellion reports that the struggle is not over: “While a Supreme Court Commission has been named to investigate the human rights abuses, Oaxacans have little faith that a real difference will trickle down. Despite the dead-end government redress the air stirs with the force of a familiar slogan: ‘We will never be the same again.’ The city walls seem to share this sentiment, planted in the post-repression graffiti: ‘Esta semilla germinará,’ from this seed we will grow.”

The First-Hand Accounts

The many featured interviews illustrate the spirits of spontaneity, anti-authoritarianism, and self-defense that were fundamental to the uprising. There is Jenny’s account of accompanying the family of slain US independent journalist Brad Will. The family had traveled to Oaxaca to demand justice for Brad and for all victims of government repression. Cuautli recounts his experience working in the community topiles (basically a people’s police force), formed during the occupation of Oaxaca City, as community defense groups protecting people from government repression as well as “common criminals” who preyed upon other poor people.

Tonia, recalls the women’s “Pots and Pans March” of August 1, 2006, which sparked the spontaneous takeover of the Channel 9 television and radio station by thousands of women. “When we got to the Channel 9 offices, the security guard didn’t want to let us in…The women in the front were asking permission for an hour or two to broadcast, but the employees of Channel 9 said it was impossible. Maybe if they would have given us that one hour and cooperated, then it wouldn’t have gone any further. But with them seeing the number of women present, and still saying no, we decided, ‘Okay then, we’ll take over the whole station…’ Everyone was taken by the spontaneity of it all. Since no one had foreseen what would happen and no one was trained in advance, everything was born in the spur of the moment…One thing I liked is that there were no individual leaders. For each task, there was a group of several women in charge.”

In the middle of the night, August 21, 2006, paramilitary forces destroyed the antennas at the occupied Channel 9. The social movement took immediate action in support of the women, fighting off the police and paramilitary attackers at the antennas, and spontaneously deciding to occupy all eleven of the city’s commercial radio stations. Francisco, an engineering student and radio technician who first got involved with the movement when Radio Universidad was vandalized by apparent police infiltrators, describes these actions from the front lines. He was working the night of August 21 at Radio Universidad when word went out that occupied Channel 9’s Radio Cacerola was down, and people were being attacked at the antennas at Fortín Hill. Francisco recounts, “we got up from our seats and left immediately…We grabbed whatever was available: Molotov cocktails, sticks, machetes, fireworks, stones, and other improvised weapons. But what could we do with our ‘arms’ against Ulises Ruiz’s thugs, who carried AK-47s, high caliber pistols, and so much hatred? Still, we had a lot of courage, the group of us, and in that moment the only important thing was getting to the place where our compañeros were under attack…We made it thanks to our skilled but funny-looking driver, Red Beard, who wore round-framed carpenter goggles covering half of his face, a yellow fireman’s helmet, and red beard. In truth, we all looked pretty funny in our protective gear: leather gloves and layered t-shirts. But wasn’t funny at all was the sound of bullets and screams that we heard on the other side of the hill as we continued onward.”

The busload from Radio Universidad arrived on the tail end of the government attack, and when they met up with their compañeros, they were told that police had shot and injured several people and destroyed the antennas. They searched for any injured compañeros who remained, then left to go help elsewhere. After visiting Radio La Ley, which had just been occupied, they were inspired to take over another station themselves and went to Radio ORO: “When we got there, we knocked on the door of the station and announced with a megaphone: ‘This is a peaceful takeover. Open Up. We are occupying this radio because they’ve taken away our last remaining means of free expression. This is a peaceful takeover. Open Up!’ The security guard opened the door and we entered, without anyone being hit, without insults—we just walked in.” Francisco concludes, “after the takeover, I read an article that said that intellectual and material authors of the takeovers of the radios weren’t Oaxacan, that they came from somewhere else, and that they received very specialized support. The article claimed that it would have been impossible for anyone without previous training to operate the radios in such a short amount of time because the equipment is too sophisticated for just anyone to use. They were wrong.”

Another account comes from former political prisoner David Venegas Reyes, who co-found VOCAL (Oaxacan Voices Constructing Autonomy and Liberty) in February, 2007, for the purposes of challenging the more mainstream and hierarchical elements within the APPO. David, who in October, 2006 was named representative of the barricades to the APPO council, recounts defending the barricades formed after the August 21 radio occupations: “we asked ourselves, ‘how can we defend these takeovers and defend the people inside?’…that’s when my participation, along with the participation of hundreds of thousands of others, began to make a more substantial difference. Because the movement stopped being defined by the announcements of events and calls for support made by the teachers’ union and began to be about the physical, territorial control of communities by those communities, by way of the barricades.”

David recounts that “We originally formed the barricade to protect the antennas of Radio Oro, but the barricade took on a life of its own. You could describe it like a party, a celebration of self-governance where we were starting to make emancipation through self-determination a reality. The barricades were about struggle, confrontation, and organization. We eventually started discussing agreements and decisions made by the APPO Council and the teachers’ union. There were a number of occasions where the barricade chose actions that went against those agreements, which in my view, only strengthened our capacity for organized resistance.”

David says VOCAL “stemmed from an APPO Statewide Assembly when it became evident that there were divergent perspectives with regard to the upcoming elections.” One side felt that the APPO movement “in all its plurality and diversity,” had purposefully excluded “political parties and any corrupt institution,” so getting involved with elections would “attack the unity constructed from diversity of thought and visions that exist within the movement.” The other side wanted to “act pragmatically and participate in the elections with our own candidates.” Those not wanting to participate in elections “that serve to legitimate repressive governments,” and who were distrustful offormed VOCAL. Consequently, VOCAL “turned into a diverse organization where a lot of anti-authoritarian visions and ways of thinking coexist—some rooted in indigenous tradition, like magonísmo, and some more connected to European ideologies. A lot of compañeros who have no particular ideological doctrine are also active in the organization…What we all have in common is our idea of autonomy as a founding principle. We defend the diverse ways of organizing of pueblos and the rights of people to self-govern in all realms of life…Unlike other hegemonic ideologies, we don’t believe that to promote our own line of thought it’s necessary to exclude anyone else’s.” organizations that did,

In April 2007, David was arrested, “with no arrest warrant or explanation. They drove me to an unknown place, where they planted drugs on me, then tried to force me to hold the drugs so that they could take photos. When I refused, they beat me…Finally they presented me with the arrest warrant that accused me of being involved in the social movement and the acts of November 25th. The warrant accused me of sedition, organized crime, and arson. Even as the government fabricated the idea of accusing me of drug possession in an attempt to criminalize and discredit me, they already intended to present the arrest warrant of a political nature once I was in jail.”

On March 5, 2008, after nearly a year in prison, David was released, after he was judged not-guilty by the court on all political charges. However, the CASA Collective’s website reports that since drug charges were still pending, “he was released on bail and forced to report to the court every week for over a year, severely limiting his ability to travel.” On April 21, 2009, Oaxacan judge Amado Chiñas Fuentes found him not guilty on “charges of possession with intent to distribute cocaine and heroin.” Following this verdict, David said, “This innocent verdict, far from demonstrating the health or rectitude of the Mexican legal system, was pulled off thanks to the strength of the popular movement and with the solidarity of compañeros and compañeras from Mexico and various parts of the world. The legal system in Mexico is corrupt to the core and is a despicable tool used by the authorities to subjugate and repress those who struggle for justice and freedom.”

Oaxaca: Three Years Later

Three years since the Oaxaca uprising that was sparked by the June 14, 2006 police assault on the striking teachers, the issues behind the rebellion have not been resolved, Governor Ulises Ruiz Ortiz is still in office, and Oaxaca is still in the news. A 2007 article, The Lights of Xanica, reported on the continuing struggle of the Zapotec community of Santiago Xanica in the Sierra Sur of Oaxaca. In 2009, a controversial U.S. Military-funded mapping project in Oaxaca has met local resistance this year. In May, El Enemigo Común reported that State and Federal police forcibly evicted “community members who had been blocking the entrance to the mining project Cuzctalán in the municipality of San José del Progreso since March 16.” Recently, Narco News reported on heated negotiations between the government and Section 22 of the National Education Workers Union (initiators of the 2006 strike), as well as a robbery and murder committed by State Agency of Investigation agents at a bus terminal in Oaxaca City.

On June 8, 2009 The Committee in Defense of the Rights of the People (CODEP-APPO) reported the assassination of Sergio Martínez Vásquez, member of the State Council of CODEP, arguing that the“way in which it was done and due to some information gathered, everything points to the fact that the material actors of this assassination were paramilitary groups that Ulises Ruiz has operating in the region.”

On June 14, a march in Oaxaca City commemorated the three year anniversary of the 2006 uprising (read report in English or Spanish), and on June 17, a protest encampment in the Zocalo of Oaxaca City was attacked by paramilitaries (read report in English or Spanish).

The future in Oaxaca is unclear, but it is certain that the people will continue to resist, and international solidarity with help to strengthen the local resistance. Be sure and visit www.casacollective.org for the latest reports and opportunities for international solidarity.

Hans Bennett is an independent multi-media journalist whose website is www.insubordination.blogspot.com.