Stories from the Grassroots Mobilization in Oaxaca

By Duygun Gokturk

Political Media Review

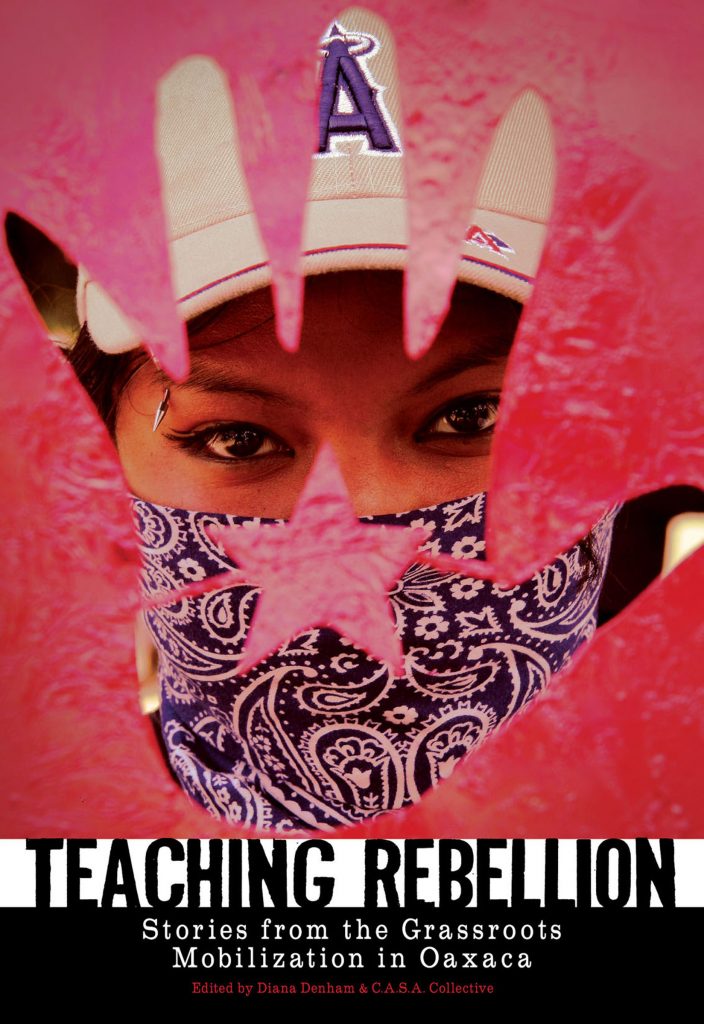

Teaching Rebellion; Stories from the Grassroots Mobilization in Oaxaca reflects the spirit of the historical teachers’ struggle in Oaxaca, Mexico in the spring of 2006, which is rooted in the principal of radical (direct) democracy and social justice. The narratives assembled in this book are the voices of political implications of theory drawn from the experimental frameworks within this community struggle for “living wage, infrastructure repair, free school books and social services for poor students” (p.25). As the authors state, this book “is not a definitive assessment of the movement that took shape in Oaxaca in 2006, nor is it a comprehensive collection of the stories that people lived and carry with them…it is an effort to represent a cross-section of Oaxacan society, to reflect both the diversity of actors and the diversity of their experiences…”(p.21). This grassroots mobilization characterizes the movement active in challenging societal structures first started by the National Union of Educational Workers in Oaxaca. After a short while, unification of various citizens’ mobilization has evolved into one of the largest and most tactfully organized community struggles in the country, and at least a million people have taken to the streets to demand social justice. Within Teaching Rebellion the centrality of praxis activates capacities, ideals and solidarities capable of challenging and reformulating societal structures. As one indigenous community radio activist stated, “once you learn to speak, you do not want to be quiet anymore”.

Throughout the book, we are witnessing new forms of organized struggle as a result of the policies applied by eighty years of single party rule of Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) and its hegemony which “compress critical space and stifles critical thought” (Hill, 2003, p.1) within the social and political spheres. Under the control of PRI, the concrete realities within the city of Oaxaca inform us that “corporate-led development projects have targeted communal lands rich with natural resources and biodiversity, dismantling indigenous people’s rights to self-determination and ravaging their means of economic sustainability” and as a result the majority of the population is “disproportionately burdened with poverty” (p.27-8). PRI’s economic policies serve to perpetuate the interest of neo-liberal policies in the interest of dominant hegemony and situate itself involving in the neoliberal model of education. The widespread poverty and marginalization as a result of state powered neoliberal policies concludes periodic waves of social revolts that have the capability of being constant foe of the government. In the first place, the street protest of teachers starts and evolves into one of the largest struggles in the country. Throughout the struggle the sites of resistance organize under the name of The Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca (APPO), a community organization that is rooted in dialogical communication through an involvement of its members in policy making processes. The movement develops an integration with media in order to promote alternative ways of communication and through media networks has the chance of speaking for itself. Radio Universidad becomes the voice of the movement and offers a medium to transmit their struggles.

At one of her speeches, Arundhati Roy said, “We know of course there’s really no such thing as the ‘voiceless’. There are only the deliberately silenced, or the preferably unheard” (Jaramillo, 2005, p.xxx). In this book the preferably unheard and deliberately silenced voices insist upon recreating their own struggle in its own image and language which is a way from stripping its own agency based on the movement’s principles of social justice, radical democracy and humanist values. Each voice within the book “denaturalizes the mythic status of oppression” and the light surges from the new pedagogy entries into oppression’s closed rooms (Jaramillo & McLaren, 2009, p.3).

The collection of diverse voices show us how struggle is lodged within and with the praxis, and at this point some of their words are worth quoting at length.

Eleuterio (as a primary school teacher): “A whole movement began to promote authentic indigenous education…but the general current in the government says that everything indigenous is backwards. If we keep being ‘Indians’, the nation won’t progress” (p.45).

Marcos (as one of the founder of APPO): “It is not enough to know that we want change; we have to know what kind of change we want and how to bring about that change” (p.83).

Genoveva (as a member of Oaxacan Women’s Coordinating Body): “for a long time women did not have a voice or a vote in the communities; the men decided everything. But today’ spaces are opening up for women little by little” (p.126).

Silvia (as a defender of Radio Universidad): “On the streets, we learned to be more human” (p.205).

Adan (as an elementary school principal): “Social movements can sometimes be short-sighted. We’re looking for ways to move into the future” (p.325).

Each of these voices prove to us that the movement created its own definition of the good life which is “beyond development”, “beyond economy”, “beyond individual”, “beyond the nation-state” (p.332), and do not accept globalization that has “two attractive masks: as a political mask ‘democracy’, and as an ethical mask, ‘human rights’” (p.333). The movement has its own definitions for “democracy” and “human rights” that allow a space for each human being below, above and within them.

As final words, the book reminds us the poem of Nazim Hikmet, Optimism, (Blasing & Konuk, 2002, p.204) which says;

The world’s no run by governments or money

But people rule

A hundred years from now

Maybe

But it will be for sure…

References

Denham, D. and C.A.S.A Collective. (2008). Teaching Rebellion. CA: PM Press.

Hill, D. (2003).Global Neo-Liberalism, the Deformation of Education and Resistance. Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies, Volume 1, Number 1.

Hikmet, N. (2002). Optimism. In R. Blasing and M. Konuk (Ed.), Poems of Nazim Hikmet. New York: Persea Books.

Jaramillo, N.E. (2005). Preface. In Peter McLaren (Ed.), Red seminars: Radical excursions into educational theory, cultural politics, and pedagogy. New Jersey: Hampton Press Inc.

Jaramillo, N. and McLaren, P. (2009). Borderlines: bell hooks and the Pedagogy of Revolutionary Change, book chapter in Critical Perspectives on bell hooks, edited by Lupe Davidson and George Yancy, Routledge: New York.