Dan La Botz

July 6, 2010

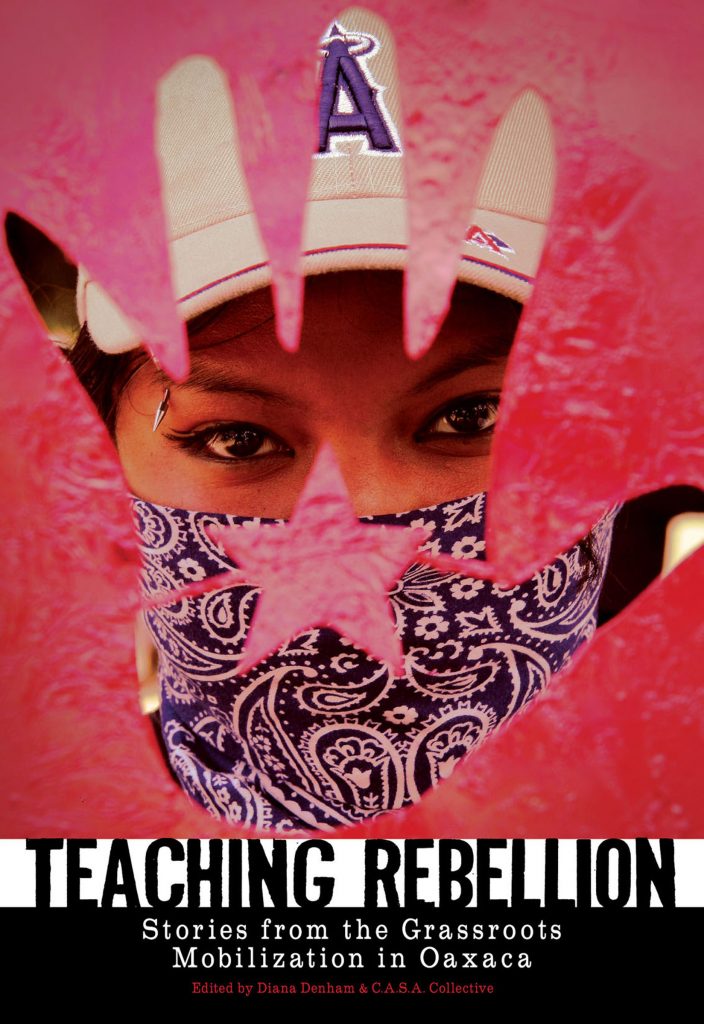

Diana Denham and the C.A.S.A. Collective, Teaching Rebellion: Stories from the Grassroots Mobilization in Oaxaca (Oakland: PM Press, 2008) and Diario de Oaxaca: A Sketchbook Journal of Two Years in Oaxaca (Oakland: PM Press, 2009).

The young PM Press of Oakland has published two interesting and quite different books about the civic uprising in Oaxaca in 2006.

Teaching Rebellion by Diana Denham and the C.A.S.A. Collective brings together 23 interviews with people who participated in or were caught up in the Oaxaca rebellion together with a concluding essay by Gustavo Esteva and a study guide by Patrick Lincoln. The book is profusely illustrated with photographs. Peter Kuper’s Diario de Oaxaca: A Sketchbook Journal of Two Years in Oaxaca is a beautiful and bilingual book of drawing, paintings, cartoons, and photographs — a collage of the two years he spent in the city with his family.

The interviews in Teaching Rebellion were done by the C.A.S.A. Collective, “a group of international activists, human rights observers, and volunteers for grassroots organizations.” The 23 subjects of the interviews come from many walks of life in Oaxaca — teacher, student, housewife, vendor, reporter, and many others. The oldest person interviewed was in her 70s and the youngest just 9 years old, though most were young adults and middle aged people who had taken part in the movement, including involvement in the Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca (APPO) which became for a while a kind of alternative government, peoples’ government in the city. The interviews constitute a view of the movement from the grassroots.

All of the important events of the Oaxaca Commune, as some have called this experience, are discussed from the teachers’ sit-in, to the mega-marches, to the movement’s seizing of the radio stations, and the creation of APPO. Personally, I found most moving the testimony of Aurelia, a 50-year old illiterate maid who had not participated in the movement, but who found herself caught up in the repression, mistreated, insulted, flown out of Oaxaca and jailed in the state of Nayarit. Her story, and the stories of others who faced repression — including the 20 killed by death squads — remind one of the tremendous force of the state unleashed against participants in the movement.

What seems missing from these interviews, however, is any discussion of the internal political debates within the movement. For example, we have no real discussions of the conflicts within the Oaxaca local of the Mexican Teachers Union (el SNTE) or between el SNTE and the APPO. The leftist groups that existed in both the SNTE and APPO and in the movement, such as the Communist Party Marxist-Leninist of Mexico and the Popular Revolutionary Front, are not mentioned. The guerrilla group, the People’s Revolutionary Army (EPR), is mentioned but not really discussed by any of the participants. Since all of these groups were, to one degree or another, actors in the 2006 uprising, so one wonders why the C.A.S.A. apparently avoided talking with people who would have identified themselves as members of one of these groups, so that they could discuss their political views. What was the interaction between the grassroots activists portrayed here and the political organizations? The absence of a discussion of these groups and their politics leads one to feel that the book has been sanitized, presenting all grassroots activists as political innocents.

One also feels — though the authors should not be faulted for this — that we would like a more complete vision of the Oaxaca events of 2006. We need other books that tell us what Governor Ulises Ruíz of the Institutional Revolutionary Party and President Vicente Fox were doing and thinking at the same time. We want to know what the local political and political and police authorities in Oaxaca talked about during the rebellion. We would like to know what the very rich of Oaxaca did during the rebellion as well as the comfortably well off. What was the larger social and political picture into which this civic uprising fit?

Kuper, his wife and daughter arrived in Oaxaca in July 2006 and spent two years there, years which he recorded in his sketchbooks. As he writes, he felt compelled to capture Oaxaca’s “dark times” but also to “capture its light.” Kuper’s sketchbooks — turned into what is a beautiful, colorful art book — accompanied by a bilingual diary, touch on all the famous sites and activities that tourists find and locals know in Oaxaca. His drawings are clever and campy, kitch and corny, funny and wild. Anyone who has spent some time in Mexico and particularly in Oaxaca, will be reminded looking at this book and reading the text of their own experiences. The book is charming.

In truth, the events of the upheaval of 2006 represent only a small part of this book. Kuper has captured much more of Oaxaca’s light than of its dark times. That too proves useful, allowing us to situate the year of upheaval within the broader context of a city filled with tourists and visitors like Kuper himself.