By Chris Steele

Truthout

April 17th, 2018

Two members of the Black Panther Party are met on the steps of the State Capitol in Sacramento, May 2, 1967, by Police Lt. Ernest Holloway, who informs them they will be allowed to keep their weapons as long as they cause no trouble and do not disturb the peace. Activist scott crow says the Black Panthers inspired his own theory of liberatory community armed self-defense.

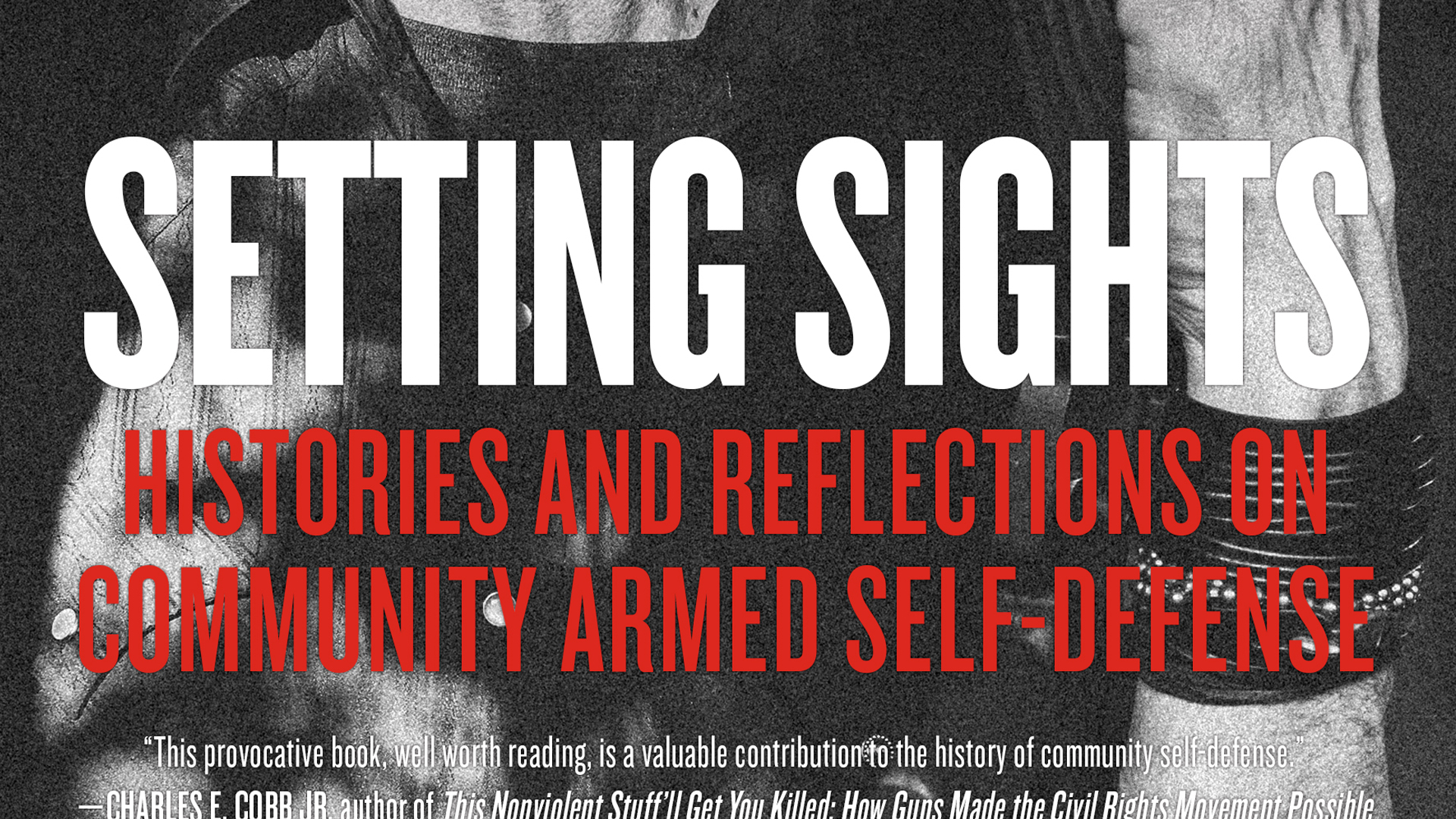

According to an FBI Joint Terrorism Task Force memo, author and activist scott crow is “… considered armed and dangerous. He is proactive in civil disobedience skills and goes to events to instigate trouble.” Having been involved in myriad organizations and direct actions ranging from anti-racist to environmental to disaster relief, crow was under surveillance and investigation by the FBI for at least three years for political activity relating to anarchism, animal rights and environmental activism. crow’s book Black Flags and Windmills: Hope, Anarchy, and the Common Ground Collective, tells the harrowing story of going into New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina, where he co-founded Common Ground Collective, now known as the largest anarchist organization in modern history. Building off his experiences in New Orleans with armed self-defense, horizontally-organized disaster relief aid and FBI informants, crow is the editor of the newly released anthology Setting Sights: Histories and Reflections on Community Armed Self-Defense. In this interview with Truthout, crow discusses his experience with armed self-defense, the current gun control debate, the student-led protests on gun control, the militarization of police, the media framing of police killings and the military-industrial complex.

Chris Steele: Can you elaborate on your experience in New Orleans when you engaged in temporary armed self-defense and what the result was?

scott crow: I was one of two white men invited into part of the Black Algiers community to take up community armed self-defense — from my relationship with former New Orleans Black Panther Party chapter leader Malik Rahim through our work to free political prisoners, the Angola 3. They asked for armed support to protect themselves against white vigilante groups and the New Orleans police that were out of control before [Hurricane Katrina], and were more lawless after. What I saw when we arrived was criminalization and indifference [toward poor, Black communities all over the city] from government at all levels. Racism and fear dominated the media and [the narrative] on the ground.

While people were literally dying or suffering, the state put emphasis on restoring “law and order” above saving or helping tens of thousands of people. The police were turning a blind eye as the white vigilantes calling themselves the “Algiers Point Militia” drove around in trucks, drunk, with loaded weapons, intimidating and killing Black men on the streets. My first duty on showing up to Malik’s was to cover a bullet-riddled, shirtless dead body of a man with sheet metal. Who killed him: the police or the white militia?

So, we organized a community-based armed self-defense rooted in liberatory ideas. It started with five of us: three Black men from the neighborhood and two white men from Texas (one who would later become an informant for the FBI against us). It evolved into protection and defense of the neighbors within a few blocks, to the developing disaster relief spaces and clinics we were building. Suncere Shakur — who took great risk as a Black man from another city to take up arms with us — also guarded Malik, whom the vigilantes were threatening.

In short, we ended up in a brief armed standoff with the militia, and law enforcement continued to harass volunteers and almost murdered me on four occasions within the first month by putting guns to my head and threatening to “blow my fucking brains out.”

From these rudimentary defense efforts, we built a decentralized disaster response organization and network called the Common Ground Collective (now known as Common Ground Relief) to help defend and rebuild these communities with them.

Can you explain how these experiences in New Orleans led you to writing and putting together your latest book, Setting Sights?

Everything is built on something that came before it; when we took up arms, we were building on liberatory histories before us — from anarchist ideals, the Zapatistas in Mexico and the Black Panthers. All of these disparate tendencies gave us foundations to build from. I had also read many other smaller stories over the decades of historically marginalized groups or communities taking up temporary arms as part of larger survival efforts, but realized that none of them had ever been told together — as collective narratives with similar underpinnings. From my actions in New Orleans and the trauma from it, I began a process of reflecting on and developing the ideas of liberatory community armed self-defense as a theory.

And remember, at the time this was happening in New Orleans, the so-called left was almost virulently anti-gun and deeply in the methods of nonviolence. We were almost seen as “illegitimate” for this praxis. The ideas of community armed defense only found acceptance within largely white anti-fascist networks I was part of, and in a handful of militant Black radical traditions only.

With new attention and student-led protests advocating for gun control, where do you think the debate should start?

I think students — and all of us, really — have to fundamentally understand three things in talking about gun issues. One, that government is not going to make a violent society go away; only we will, by working together to shift culture in the ways we handle violence and conflict in this country. We live in a country founded and maintained by violence. We can ask, “What are the ways we can subvert and break the toxic cycles of both individual or personal violence, and state-sanctioned violence by entities like the police, military or court systems?”

Secondly, people need to see through the political lies that laws will protect us. More gun laws don’t and won’t always make us safer, especially relying on weak politicians who are in the pockets of corporate arms dealers to enact substantive gun reforms while they are being showered in money.

Thirdly, “law enforcement” officials claim to be against guns and for stemming violence, but they themselves are more heavily armed than most militaries around the world. Let’s not forget it was the FBI [and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms] who just two years ago — in blatant disregard for human life as well as domestic and international laws — armed Mexican drug cartels with high-powered rifles which were used to kill innocent civilians on both sides of the border.

The debate should start with questions that lead to deeper conversations. How do — or can we — take this complex cultural symbol, the gun, and decouple it from what it means to very different people? How do we deal with violence in the US, including guns? What responsibilities do we as individuals and communities want to take in dealing with violence? Are there legitimate roles for firearms, and do the benefits outweigh the challenges? How do we culturally shift from guns being sold with fear and masculinity to something else?

Can you explain where liberatory community self-defense and gun control are compatible?

I am not sure if they are, except in very limited ways. In the 30 years I have been in the political sphere, I have been on both sides of this debate. I used to unwaveringly support more gun laws, but like many ills of society, I kept seeing stricter laws weren’t doing what they intend, and only criminalizing people and communities already marginalized. That said, I don’t think any of us have a magic answer to these very deep and complicated issues that touch many lives in varying ways.

Part of calling for a liberatory approach to community self-defense is calling for sensible gun ownership. To me, that means a few things, like that we are not all armed to the teeth; some in communities may not even be armed at all, or it’s on a rotational basis. We don’t need individuals or communities with access to guns everywhere — laws or no laws. That community (whatever makes it a community) must decide something important like that.

Another aspect of the liberatory approach is that it hopefully challenges the ways we engage in conflict and the toxic masculinity that is within current gun culture, individually and in groups, especially with arms involved. I believe if we begin to change our approaches to conflict and violence, that these are pieces toward subverting the dominant paradigms, just like any other cultural issue.

Even if the US did pass strong gun control reform like Australia, do you feel that gun violence in the US could be curtailed?

I don’t think at this time that could ever happen in the US without a lot of bloodshed from many groups of right-wing leaning people, including white militias, sovereign citizens, neo-Nazis and even spineless politicians, who at least claim that there would be “bloodshed” if that happened. These are entrenched cultural norms outside of liberal circles, tied to other cultural “conservative” institutions like church or family that are deeply embedded. Removing guns or any other part of that culture is seen as nothing less than an attack, and people can do desperate things when they think they are being attacked; just look at the standoff at Ruby Ridge in the 1990s.

Again, that said, even though I have thought about these issues from multiple angles for decades, I am still unsure of all the paths that will lead us to stop mass shootings, and I don’t want to close the door.

How would gun control affect communities of color and liberatory armed self-defense communities?

We can already see that current gun control laws disproportionately affect poor [communities] and communities of color. For example, we have been in a crisis in this country through mass shootings or workplace shootings, which we should call it what it is: white male terrorism. And still, law enforcement handles those killers differently from the first time they arrive on the crime scene through the court phases (for those that don’t kill themselves). In many instances, the perpetrator can walk away without being shot, while police continue to kill Black unarmed men almost daily. And if we look at the legal aspects, once again, people of color are treated disproportionately unlawfully.

White nationalists, neo-Nazis and “alt-right” fascists have continued to murder and terrorize historically marginalized people and communities to this day, stockpile weapons and call for mass genocide and exclusion, but the FBI barely lists any of these individuals or groups as terror threats or go after them. Instead, they chose to target Black groups who armed themselves for protection, but have never killed anyone, like the Huey Newton Gun Club or Rakem Balogun (born Christopher Daniels), as “Black Identity Extremists” instead.

A liberatory approach challenges the assumptions that law enforcement is unbiased or fair or even helpful to any communities, but especially marginalized ones. It also starts with the assumption that these communities know better how to be able to collectively defend themselves from racist attacks, whether by the state or right-wing paramilitaries like the militias.

You pointed out that Black people are being killed on a near-daily basis by the police. Can you speak on the recent police killings of Stephon Clark and Danny Ray Thomas, and the acquittal of Alton Sterling’s killers? How these killings are framed in the media? Where the gun debate is during this coverage?

I can only speak to the larger patterns and histories of police murdering Black people, and not individual circumstances. The media — which we have to recognize is part of Power (which includes any entities that have undue amount of influence or control on our lives) — almost always fall lockstep into the larger narratives in these police murders. First is justification. The media unquestioningly back the “official law enforcement narrative.” Secondly, the media never question the militarization of the police and their ability to kill unarmed civilians without consequences. Lastly — and possibly most important — is the often, inherent racism in how police respond to people that possibly have guns and how they are portrayed. If they are Black, narratives of “criminal” or “dangerous” are used, especially if the police killed them; whereas in similar or worse situations involving white men, [white perpetrators] walk away alive from it, and the media portray them as “lone wolves” with “mental issues” or other sympathetic tropes.

In corporate media portrayals, after the police kill another innocent person, the gun debate only focuses on guns being in the hands of so-called dangerous criminals, or other racist tropes that hold the murdered individual to one standard while the police, as an institution, are never questioned in their access to weapons or ability to kill with almost impunity. Law enforcement can murder at will without question in corporate media. They never ask questions like, “Should the police be armed at all?” Instead, they perpetuate often racist or sensationalistic coverage.

With the US having a higher military budget than the next 10 countries combined, can you speak on the military-industrial complex and how it is often left out of the gun control narrative?

When the so-called gun debate is had, it’s always framed as “individual’s rights” and rarely (if ever) about the killing capacity of the military or law enforcement. We cannot have over 2 million people who served in the military and taught to kill with weapons not be affected by that; and in turn, we cannot pretend that violence is only a moralistic failure by individuals. It is internalized by all of us in civil society. This country was built on — and is maintained — by violence domestically and abroad, and this is a national disaster.

If we keep funding war and occupation everywhere, it will continue to reflect on elements of our societies. Dismantle the occupying militaries, the policing and prison systems. We’ve tried them, and they don’t work for most of us. Let’s rebuild localized deeper and broader health care, education, family support and other foundations of civil society that help us deal with conflict individually and collectively to defend and liberate ourselves on our terms.

NOTE: This interview has been lightly edited for clarity. Copyright, Truthout. May not be reprinted without permission.

Chris Steele co-authored an article with Noam Chomsky that was published in the latter’s book Occupy: Reflections on Class War, Rebellion and Solidarity.