By Ben Curttright

The Philadelphia Partisan

May 15th, 2018

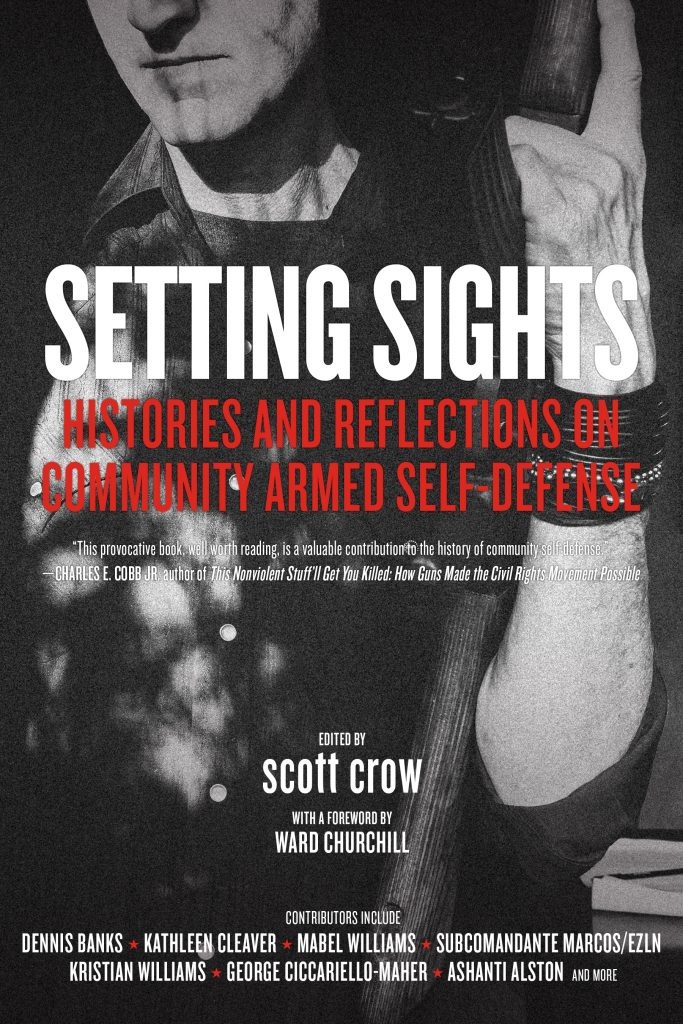

If Setting Sights has a single thesis, it’s that support for gun control is not an inherently left-wing position.

This is a particularly hard sell in the United States, as author and historian Neal Shirley admits. Those opposed to gun control “tend to be right-wing, pro-government folks in their practical attitudes toward domestic and international military and police repression, yet somehow they see themselves as fighting against government control.” The National Rifle Association (NRA) has spent over $200 million since 1998 lobbying, campaigning for, and contributing to the campaigns of (predominantly) Republican candidates. A large majority of domestic terrorist attacks are committed by right-wing extremists. On February 14, a 19-year-old gunman, Nikolas Cruz, killed 17 people at his Florida high school with an AR-15. As if drawn to match Shirley’s description, Cruz was a former ROTC member who allegedly trained with white supremacist groups (though these claims have been disputed) and posted Islamophobic rants on Instagram; in his profile picture, he’s wearing a MAGA hat.

It makes sense to think of the right-wing gun nut as performing at the logical endpoint of the nationalist/imperialist ideology that’s dominated the U.S. since World War II and especially since 9/11. America is the global cop; the most venerated of its servants are the troops; the truest way to embody these ideals in this atomized, individualistic world is to buy a gun and declare oneself a cop, swearing to protect and serve the “Real America.”

In a 2017 survey, the Pew Research Center found that Americans across the mainstream political divide generally support the most frequently suggested gun control proposals, including universal background checks, barring gun purchases by people on terror watch lists, and preventing the mentally ill from purchasing guns. These proposed laws range from cosmetic to discriminatory, given their reliance on repressive, undemocratic organs of the American state like police databases and the FBI no-fly list. Meaningful gun control measures, like bans on assault weapons and high-capacity magazines, poll significantly lower. What’s most interesting, though, is how the policy proposals that Pew asked about would largely leave the status quo intact: most gun owners are white men; most gun deaths are by handgun, not assault rifle; and mental illness generally does not cause gun violence (though mental health background checks might still matter; two-thirds of gun deaths in the U.S. are suicides). Pew didn’t ask about buybacks or handgun bans, policies that have reduced gun violence in countries around the world. And, crucially, they didn’t ask about the police, who shot and killed 987 people last year.

Setting Sights aims to provide an alternative framework for thinking about guns. The authors, writing primarily from an anarchist tradition, reject the liberal consensus on gun control: “that violence is bad, and guns are often used in violence, therefore guns are bad, therefore it would be better if the government was the only entity able to use them (presumably against everyone else?).” Instead, they see guns as a “fact of life” for any social movement, a necessary tool for those who resist power. “Guns are like forks,” quotes the Western Unit Tactical Defense Caucus. “You may not believe in forks, but that doesn’t mean they don’t exist and aren’t a useful tool for the revolutionary. Guns, like forks, have a use and a purpose within the revolution. Quite simply put, guns are tools.”

Tools, yes; “like forks,” not so much. Whether arguing, as scott crow does, that “if we want to transcend violence in the long term, we may need to use it in the short term” or asserting “the right of oppressed peoples to protect their interests by any means necessary,” firearms must, by any self-interested social movement, be treated more seriously than forks.

Who is made safer by gun control? Who, if anyone, is made less safe? If guns are tools, then when and how should they be used, and what ends are worth their use? And, ultimately, are guns necessary for the Left to win the future?

Maybe. Setting Sights largely elides the question of full-scale revolution in favor of a discussion of community armed self-defense as a means of protection against both reactionaries and the state. As gun control, for once, lingers in the national discourse, making these assessments of tactics and consequences is perhaps more important than ever.

In 1967, French philosopher Régis Debray published Revolution in the Revolution?, a slim book on the successes of the Cuban revolution that quickly became required reading for would-be guerrillas in the Americas, alongside Che Guevara’s own manual on guerrilla warfare. Debray’s essay advanced foquismo, a combat strategy based on small, hypermobile guerrilla units that attack from secret strongholds without aiming to take or control territory. The guerrilleros would instead remain a clandestine, specialized force, detached from peasant society but, through acts of armed propaganda, demonstrate the ability of the people to resist state power. The text is particularly critical of Trotskyism (“Trotskyism flies in the face of common sense”) and the Trotskyist insistence on organizing the revolution within the peasantry and trade unions. The foco, not the union, is, according to Debray, the vanguard of the working class.

Debray’s theory of the foco was implemented in several countries and contexts; the results were, on balance, not good. Che Guevara was captured and killed in Bolivia in 1967 while recruiting for a guerrilla group. According to George Ciccariello-Maher’s essay in Setting Sights essay, foquismo “proved disastrous” in the Venezuelan guerrilla struggle of the 1960s, as guerrilla groups were unable to establish the political base among the peasant masses that makes warfare sustainable. The split between Students for a Democratic Society and the more radical Weatherman faction was directly inspired by Debray’s book, which became the blueprint for the ill-fated Weather Underground Organization in the U.S. (whose hard-line politics made them one of the most intellectually interesting, but least politically effective, groups to emerge from the American New Left).

Political texts, Debray writes in his 2017 preface to the Verso edition of Revolution in the Revolution?, are “wagers on the future, laid instinctively, in the excitement of a unique, unrepeatable moment, when form is not available to sublimate content, for they are generally bereft of style or captive to a logomachy peculiar to their time.” Upon reflection, according to Debray, the collective wager of foquismo was not won; meaningful political and social changes were “not achieved by armed vanguards, but by the reconstruction of trades unions, implantation in the shanty towns, and the revival of united opposition fronts and specifically political organizations.”

Debray’s honest self-criticism is born from an understanding that armed struggle, in its various forms, is a tool. If a tool is useful, it should be used; if not, it should be dispassionately discarded. This seems to be the logic behind the second section of Setting Sights, titled “Histories of the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries”: by analyzing cases of community armed self-defense, we can assess the validity of the authors’ original claim (that guns are a necessary factor for any social movement) and better implement community self-defense practices in the future.

However, the essays, in general, proceed differently; in Setting Sights, the gun, more often than not, ends up justified whether its use was successful or not.

One of the earlier essays, a historical piece by educator Shawn Stevenson, analyzes an armed encounter between the Centralia, Washington branch of the Industrial Workers of the World and a group of Legionnaire vigilantes in 1919. Stevenson is pointedly writing against popular history, in which the 1919 skirmish was a “massacre” or a “tragedy.” He instead sees the incident as a partial victory for the Wobblies, who “took up arms to defend their right to organize, striking a blow against the bosses despite great personal sacrifice.” According to Stevenson, “A message had been sent that the Wobblies would not always submit to beatings and the destruction of their property peacefully, and few would-be vigilantes appear to have been willing to put their lives at risk in face of the example set in Centralia.”

This optimistic reading of the events sits at odds with Stevenson’s own summary of the incident and its aftermath, in which eight Wobblies were convicted of second-degree murder and IWW member Wesley Everest was taken out of jail and lynched by vigilantes. The “message” sent did not halt the “White Terror” that followed the Centralia incident, a citywide scare in which “any working person with an association to the IWW was rounded up by vigilantes, their homes searched without warrant and vandalized.” In fact, internal disputes about militancy in the IWW, according to labor organizer Fred Thompson, proved harmful to the IWW, whose membership fell after a series of dissensions in the early 1920s. These more negative consequences do not change Stevenson’s mind about the efficacy of the IWW’s tactics; taking a “principled stand in the fight for the rights of working people” is suddenly more important to Stevenson than better understanding how to advance those rights.

crow defines community armed self-defense as “the collective group practice of temporarily taking up arms for defensive purposes, as part of larger engagements of self-determination in keeping with a liberatory ethics.” Firearms, in this reading, are not instruments of revolution but instead a tool for carving out, in accordance with anarchist principles, spaces outside the state.

The key historical example of this theory put in practice (at least when working within the American context) is the Black Panther Party, whose Ten-Point Program explicitly called for all African Americans to arm themselves in accordance with their Second Amendment rights.

In “Gun Control Means Being Able to Hit Your Target,” American Indian Movement leadership council member and ethnic studies professor Ward Churchill cites the Panthers as the only community self-defense model that was “effective, replicable, and potentially sustainable.” The Panthers’ community-building efforts in the 1960s were facilitated by the Party’s demonstrated willingness to “physically defend what had been built against those bent on destroying it,” Churchill argues.

The right of oppressed groups to defend themselves, whether against the state (see Michele Rene Weston’s essay, “Ampo Camp and the American Indian Movement: Native Resistance in the U.S. Pacific Northwest”) or against white supremacist vigilantes (see the Mabel Williams interview “Negroes with Guns” and a panel discussion between Williams, Kathleen Cleaver, and Angela Y. Davis, “Self-Respect, Self-Defense, and Self-Determination”) has been reasserted since the Parkland shooting by R.L. Stephens of Democratic Socialists of America (“In my socialism, I believe in the democratic right to bear arms among the people, not to defend against the government but because the government does not in fact protect everyone equally”) and Setting Sights contributor Ciccariello-Maher (“And so, we know that the government has no interest in prosecuting and undermining white supremacist organizations, and that organizations on the ground are going to need to do that themselves”).

This particular argument is sort of outside this reviewer’s purview. If nondiscriminatory gun control, in concert with demilitarization or, ideally, abolition of the police, is possible, the Left should advocate for gun control. At the same time, if oppressed groups organize community self-defense groups to protect themselves, white leftists can have few reasonable complaints. Long-term, the idea that armed groups of anarchists are the best defense against armed white supremacists, as described in J. Clark’s “Three-Way Fight” on post-Katrina confrontations in Algiers Point, New Orleans, feels all too similar to the reactionary (and flawed) idea that only a “good guy with a gun” can stop a bad guy with a gun.

However, the idea that guns are inherently liberatory (in former Black Liberation Army member Ashanti Alston’s words, the “liberation gun” gave the BLA “the power of the people to inject fear into the oppressor and make them do as we command”) appears throughout Setting Sights, often in the form of a warning: “Some radicals might fetishize armed struggle,” warns Wingnut Anarchist Collective member Mo Karnage, especially armed struggle by people of color. “For me, collective liberation is not about fetishizing arms as the only true means toward freedom,” writes crow. In perhaps the deepest essay in the collection, “Notes for a Critical Theory of Community Self-Defense,” philosophy professor Chad Kautzer details the dangers of “machismo and narcissism” in social movements based around the “sovereign subject” as defined by armed self-defense. The sovereign subject, Kautzer writes, actualizes freedom through asserting the individual’s right to self-determination; in doing so, the revolutionist undermines the “conditions of freedom for others.”

As Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor wrote in the wake of Parkland, any social movement that aims to deal with gun violence “will inevitably force a deeper engagement with the causes of proliferating guns, violence and the toxic masculinity that often expresses itself in gun violence.” Per Taylor’s analysis, America is a systemically flawed, violent society, bound together by “guns, violence, racism and war.”

If these factors are, as Taylor presents them, bound together like blood and sinew, then gun control should be a left-wing position. The history is certainly more complicated than that. And, if you’re on the fence about the potential for armed self-defense, Setting Sights will certainly give you a lot to think about.