By Zora Burden

RE/search Magazine

March 2017

In this interview with the long time Bay Area culture magazine REsearch crow talks about the importance in culture on shaping political ideas, industrial and electronic music and cross pollinating the two , as well as his own noise and industrial music projects from the early 80s and today. This article also appears on WIRED newswire.

ZORA BURDERN: Will you talk about how you used your music as a platform for political / social change?

scott crow: To answer that, let me give context in how music influenced and changed my life, and why and how I consciously used it later to educate and spread marginal or under-represented ideas. I spent formative years in the working-class farm town of Garland, Texas, outside Dallas. This place eventually became a dead suburb, decades after I left—like other farm towns around us. I wasn’t exposed to that much culture about the world and its politics or philosophy (outside of the basics within school), but I listened to music a lot.

Music saved my life during those alienated and nihilistic days under the shadow of Reagan, showing me a way out of the life I was living. Without the exposure music gave me to cultural and political information, I would have been at a dead end, like those around me. I desperately gained access to shared thoughts and emotions that kept me from feeling alienated and isolated.

I had grown up listening to country music and bloated album rock that was on the radio. Then Punk and New Wave hit. I was on the outer edges of the small Dallas Punk scene; it didn’t speak to my angst, nihilism or need to escape. I did get early political education and exposure from the industrial music scenes that were coming up in the mid- to late 1980’s—bands like Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy, Einstürzende Neubauten, Test Dept., Consolidated, Skinny Puppy, Cabaret Voltaire and Ministry.

The combination of clanging metal and industrial beats combined with the severe imagery, visceral videos and performances (and the political lyrics) inspired me more than fast guitars. For example, I read an interview in ’86 with Al Jourgensen of Ministry, describing in detail the issues of working-class and blue-collar people. His descriptions of neighborhoods and environments sounded just like my life. It was the first time I had encountered concepts that related to what I had felt and thought.His words exposed the differences between the American dream and my life’s actuality.

Music, both listening to it and producing it, was my only way out. In 1985 I quit high school my senior year to attend college—to study music in a nearby town for a few months (before failing in less than a year). But in that short time I was exposed to a lot: theater and art shows, late night discussions on politics, religion, and philosophy, and some acid trips. My thinking was expanded.

During this time, I had been exposed to industrial music and ambient music coming out of Europe, like Soviet France, Throbbing Gristle, Eno and—poignantly enough, I had picked up a copy of a mind-blowing book called the Industrial Culture Handbook from RE/Search, in a small bookstore in Texas. That book became a much-referenced “bible” of sorts for my friends and me during those formative music and political years.

While enrolled in college, but not attending, a friend and I did an experimental electronic noise and ambient project called Corporate Uncle. The project used found sounds, electronics and audio clips from TV to create layers. It was very influenced by Soviet France in the collage sounds but also the packaging. We released about 200 copies of our tapes, each with its own handmade chicken wire and bolt-wrapped cover in numbered editions. It was my first foray into mixing crude politics and social commentary with sounds: a far cry from the metal bands I had been in.

I started buying more electronic gear, learning MIDI and building a small studio with my meager funds from working at a record store, so I could make music on my own. In 1988, my mom scraped together some money and we both went to Europe. We had hardly ever been out of Texas at that time. It was my chance to shop my demo tapes to record labels and to explore what I perceived to be more “developed” politics and culture. In four months, I never got a record deal, but I did get a crash course in being a more politically-educated American.

Once back home, I began to write more overtly political lyrics and promoted political ideas to educate people on issues and hopefully move them to action through music. From the late 1980s until the early ’90s, I co-founded and fronted two political industrial-techno bands, Lesson Seven and Audio Assault. We had songs produced by MC 900 Ft. Jesus (aka Mark Griffin) and Information Society. Our first 12” single was “Radiation” on Oak Lawn Records, label home to bands C.C.C.P., Microchip League and Voyou. The song was basically a tongue-in-cheek sound collage, on top of a driving dancing beat, about the dangers of nuclear fallout. That release was followed by two mini-cassettes and one split CD release (between Lesson Seven and Audio Assault) on Crystal Clear records, and some compilation CDs from radio station KDGE in Dallas.

Lesson Seven toured with bands such as Skinny Puppy on the VIVISectVI tour, Nine Inch Nails and Die Warzau in the 90s. Throughout the 80s and 90s we also performed often with Consolidated, Meat Beat Manifesto, Swans, Psychic TV, Front Line Assembly, Revolting Cocks, Clan of Xymox, Laibach, Weathermen, Diamanda Galas, Severed Heads and others.

Those shows were our platform for talking about social justice and liberation from the stage. Many of the industrial bands at that time highlighted social issues, and their music had influenced me to dig deeper. Now we were performing and touring together. The bands I was in continued traveling, distributing literature, and raising money for a variety of groups from town to town.

I spoke from the stage about many issues that I now saw as connected: women’s liberation, animal rights, racism, the AIDS epidemic, abortion access, and the U.S. war machine—which was in high gear. Remember, we used to worry about Reagan fucking pushing the button to start nuclear war! The hours were grueling and long, but I believed in “dismantling the oppressive systems and creating social change”—even if I was unsure of what that would be. I thought that we could protest and vote our way to a better world if everyone got educated on the issues. (It was standard “old school” organizing.)

By morally outraging people, we could bring them to act, which meant making an appeal to power to make changes. Finally, in 1992, I exited stage left, leaving both bands after seven years of constant shows and touring. I left the music industry. It was too much industry and not enough music, politics, or steady income. The story of most artists, isn’t it?

I

turned my back on the music industry and to producing music for almost

fifteen years. I found other ways to engage in political and social

change. And I have only returned to it again in the last two to three

years. I recently added vocal tracks to anarchist hip hop artist Sole, who co-founded the influential hip hop label Anticon back in the 90s, and DJ Pain 1‘s last record Nihilismo. And

now a handful of international underground noise groups have been using

excerpts from my talks over the last ten years as cut-ups in their

sound collages. I’ve been buying gear and writing political lyrics

again, in addition to writing books.

From my experiences, I

think there is a big divide between culture-makers and most political

scenes. In political circles, the impacts from culture and

culture-makers—whether musicians, filmmakers, or “fine artists”—are

often underrated or largely overlooked. Sure, there are exceptions, like

the way Punk Rock or Industrial music was in the ’80s and early ’90s,

or the way that the new underground DIY noise and electronic scenes have

flourished in the last decade. But generally, activists and political

organizers never dive into the arts’ potential to motivate and reinforce valuable visions and ideals and messages.

On the flip side, political culture-makers are often isolated inside the subcultures where they exist. Or, they produce political work that’s not very deep or meaningful. Like Chuck D of Public Enemy said in “Revolverlution” (when talking about lyricists being short-sighted about the bigger political picture): “Let’s call it raptivism, since a lot of MCs be stuck on isms, as in sexism, self-hate, racism.” In both of those places, the mirror of self-reflection is isolated from each other. I am working now to bring it together again, through producing my own music, but also connecting artists and grassroots political movements and spaces, together.

ZB: Will you talk about some of the books you’ve written and lectures you’ve conducted?

sc: I consider myself more of a raconteur or storyteller than a writer. Writing is something I do to share stories. As a writer, I usually write autobiographically. It’s hard for me to pretend to be objective, for example, if I am writing about political or social movements.

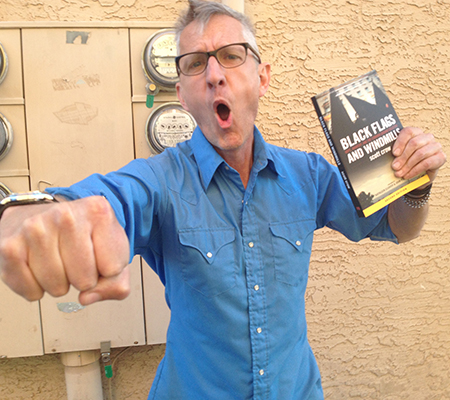

My first book was Black Flags and Windmills: Hope, Anarchy and the Common Ground Collective, which came out in 2011. It’s part personal memoir, part grassroots political-organizing manual, and part political-movement history. The primary focus was on my organizing efforts after Hurricane Katrina, through an organization I co-founded called the Common Ground Collective. The book illustrates how Anarchists were able to gather twenty-eight thousand people, over the first three years, to fight police and corruption, and work with residents to rebuild their neighborhood and communities without government “help” or interference. I think the book resonated well—a second edition, as well as Spanish and Russian editions, have also come out.

MC sole ad DJ Pain1 ‘Hostage Crisis

featuring Chris Hannah of Propagahndi

and scott crow

After that book’s release, I spent almost five years touring the US, Mexico, England, Canada and Russia doing over three hundred presentations at universities and community spaces (and everything in between). I was talking about the practical ways that the ideas of anarchy have been put into practice… and showing how communities can organize themselves without governments, corporations, or the “nonprofit industrial complex.”

Since then, I’ve had two more books come out. Emergency Hearts, Molotov Dreams: A scott crow Reader, was a collection of talks and interviews from the last five to six years. Witness To Betrayal was about my complex relationship with an FBI informant and former friend who tried to put me in prison.

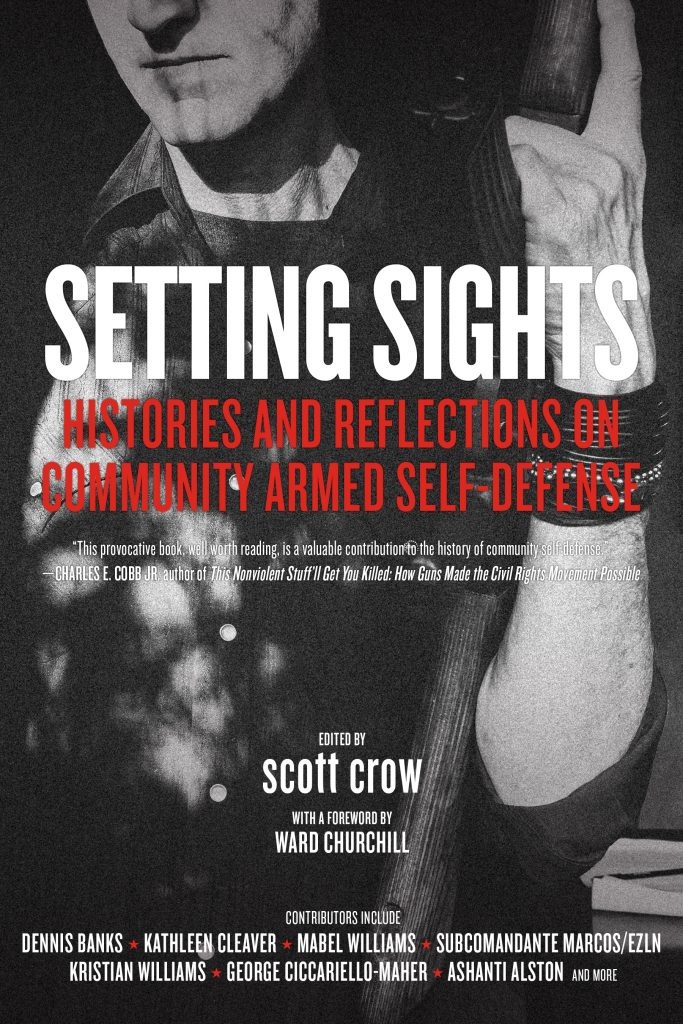

I contributed a piece to an anthology called Grabbing Back: Against the Global Land Grab (AK Press). I have two books coming out in 2018: Setting Sights: Histories and Reflections on Community Armed Self-Defense (PM Press), which is a provocative anthology on the use of guns as part of localized collective liberation efforts, and another memoir My Dangerous Years: A Memoir of Surveillance, Spying, and the War on Dissent 1999-2012, about living under surveillance as an FBI target for alleged domestic terrorism for over a decade, beginning in 1999.

ZB: Which authors or books inspired you?

sc: I have been a voracious reader, so it’s a hard list to make. Subcomandante Marcos, who is a very prolific writer, influenced me more than anything. There are so many to draw from, but reaching back, Industrial Culture Handbook by RE/Search was pretty influential on my music and politics. Manufacturing Dissent by Noam Chomsky. The Sexual Politics of Meat by Carol J Adams. Anything by Flannery O’Conner, Zora Neale Hurston, Brion Gysin, Terence McKenna, Jacques Derrida. A book called This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color. Many of the classic Beat poets and writers heavily shaped my world. In addition, there are literally piles of zines and books from unknown people who have remained in my active libraries.

ZB: What do you think political activists are facing under Trump, given his disregard for the First Amendment and The Constitution?

sc: Ideas like community armed self-defense, confronting fascists on-line and in the streets, shutting down pipelines, that black and immigrants’ lives do matter, that corporations have been destroying the world while reaping huge profits, that we cannot count on governments to save us. These are just some of many ideas that have gained a lot of ground. Conversations, actions and media platforms we didn’t have 5-10-20 years ago, are now available.

These are watershed moments. Also, the ideas of anarchy have taken root on both the traditional left and right spectrums in different flavors. People are sick of bosses and political leaders telling us what to do. People and communities are finding their own voices to stop the violence on their communities, whether it’s the police and prisons, documentation and immigration, access to clean water, or the ability to decide their own fates. They are also beginning to ask what it is they want.

How do we want to live if governments and corporations are failing? That said, this is both a time of great trials and tribulations, and times of great openings to push in new and different directions than we have before. For example, if the government de-funds Planned Parenthood, NPR or the National Endowment of the Arts—instead of begging them to reconsider or fight for them to continue, we have other paths. Look at the ACLU—they raised twenty-four million dollars in three days; the most they had ever raised in fifty years, and the reason is because enough of us saw value in that.

And if we look at the anarchist ideas of direct action: anarchy is in ascension. Fascists and proto-fascists can’t publically speak or communicate online without being shut down by anti-fascists. Direct action gets the goods. People aren’t going to wait anymore.

As activist and poet June Jordan said, “We are the ones we’ve been waiting for.” And she’s right. I don’t care whether we call it anarchy or blue potato chips, it’s the liberatory ideas and actions against the Empire and against the fascist creeps that thousands, if not millions have awakened to, and are fighting for. People are beginning to dream of other futures.

I am hopeful, but not Pollyanna-ish. We have to see these tensions as both the worst and best of times. The future is unwritten and wide open, despite how things look. Every moment is a new chance. We are standing on the edge of those futures at every turn! [end]

This origianlly appeared in V. Vale’s RE/Search Newsletter #158, March 2017

Buy Setting Sights: Histories and Reflections on Community Armed Self-Defense

Buy Black Flags and Windmills: Hope, Anarchy, and the Common Ground Collective, Second Edition