by John Stehlin

Maximum Rock n Roll

July 2015

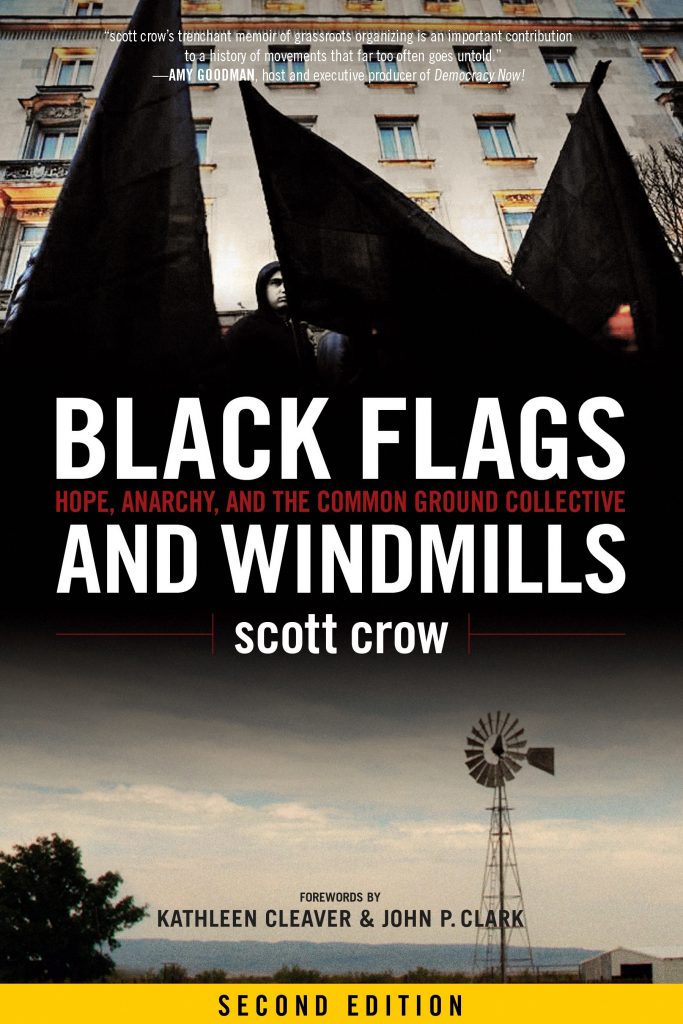

In Black Flags and Windmills, scott crow tells the story of the formation of the Common Ground Collective in New Orleans amid the chaotic aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in fall 2005, which disproportionately affected African-American communities already made vulnerable by disinvestment, poverty, and state inaction. Equal parts memoir, movement history, anarchist polemic, and organizing handbook, the book traces the early months of Common Ground’s efforts to build collective power and self-sufficiency among residents of the predominantly black Algiers neighborhood, working under the banner of “Solidarity Not Charity.” These efforts came at a time when the emergency response by federal and state agencies often ignored and even terrorized poor communities of color while residents contended with trauma, illness, violence, and the loss of homes and lives. The Common Ground story, as the many pages of glowing reviews attest, is a modern narrative of heroism without heroes, demonstrating the vitality and effectiveness of anarchist principles in the face of emergency.

This edition adds a new foreword and rewritten epilogue, photographs from the early days of the CGC, two interviews with the author, a collection of emails and communiqués from crow to supporters, CGC founding documents, and a list of the actions CGC undertook. Though I haven’t read the first edition, I think these parts alone merit another look at the book (though probably not a purchase) from people who have. They show how crow at the time envisioned and related the actions of the CGC to activist solidarity networks. This complements the main narrative, which retells the history based on recollections and oral histories from several years later. The less-than-initiated (like myself) will also appreciate the breadth of the list of tasks the CGC worked on, reproduced in the appendix. Collective members and volunteers pursued these efforts with an “emergency heart” (crow’s phrase), a horizontalist spirit, and a willingness to serve local black leaders that demonstrates anarchism at its best and least dogmatic.

Unfortunately many of the things that make this book great are also shortcomings, and because it’s justly lauded I’ll permit myself to be picky. To begin with, as a memoir the book works almost too well. crow is clearly wary of presenting the story of forming the CGC without accounting for his own formation as a white, male solidarity activist who entwined his fate with those of black residents of New Orleans. Thus, after the first few pages, in which crow and now-infamous Brandon Darby journey to inundated New Orleans in search of their comrade King, a former Black Panther Party member and community activist, the book turns to crow’s personal history and how he came to call himself an anarchist. To be very clear: this is a very important part of the story and shouldn’t be omitted. But at times it can be jarring, and, as crow clearly understands, can play into the mainstream media’s desire for a figurehead and hero. During these sections he also enters brief excurses on the Spanish anarchists of the 1930s, the Black Panther Party, and the Zapatistas. Readers already familiar with the histories of these movements will tire of these reminders. By the same token, for people new to anarchism and social movement history, these are valuable sections the book can’t do without.

Furthermore, because the story is told—rightly—from crow’s own perspective, we miss out on how the CGC evolved in the years that followed. crow left New Orleans to return to Austin after nearly two months of intense labor, punctuated by the trauma of grief, loss, and threats of violence from the state. He returned frequently thereafter, but was no longer involved on the ground in the day-to-day. From the epilogue, we know that as the emergency receded, the CGC slowly transformed into a more stable and traditional non-profit agency, while retaining a radical culture and its “Solidarity Not Charity” mission. crow seems ambivalent on this point, at times calling it cooptation and at times celebrating the valuable work the CGC still does. But we don’t get any sense of how this happened. It’s not enough to assert that Power (which crow capitalizes, in my view gratingly, to refer to the state and capital) by necessity coopts and controls. To understand what the CGC story means for future dual power organizing (both resisting the capitalist state and prefiguring its non-coercive alternative), it would help to see the steps by which it became integrated into the “non-profit industrial complex.” As a movement history, the book does not do this.

This means there are gaps in its usefulness for anarchist political theory as well. We don’t get a larger sense of why anticapitalist and anti-state movements for collective security and prefiguring a better world flourish in the gaps left by disasters, whether socio-ecological (as in Katrina) or socio-economic (as in Detroit). crow asserts that Power and the state exist only to control. But despite being punctuated by hostile interventions by the police and military, as well as ineffective ones by FEMA and the Red Cross, Algiers and the Lower Ninth Ward are places the state seemed to abandon at the time. Power (with a capital P) does control, but also controls by ignoring. This is important for anarchists to understand, but there isn’t much space devoted to these finer nuances of power. Nor is there a longer discussion of one of the most interesting aspects of the book: the sharp contrast between violent, racist, and hostile police force, and the somewhat friendlier, more cooperative military. This contrast shows in practice more shades of grey within the state than crow’s theoretical discussions sometimes admit.

Lastly, while crow never celebrates the horrific and totally avoidable disaster that created the conditions for Common Ground’s emergence, we must wonder what it takes to build dual power without some traumatic breakdown. Both anarchist solidarity activists and vulture capitalists can rush into the vacuum left by state neglect, as New Orleans since Katrina shows. At times, statements crow makes about the superiority of the horizontal tactics of the former sound eerily resonant with what you might hear from a right-wing libertarian. What the people of New Orleans deserve is a set of durable, democratic and non-hierarchical institutions that deliver the necessities of life, not a shoestring organization of overworked, committed militants on one hand and Blackwater on the other. Indeed, when CGC tried to buy public housing that was slated for demolition, really threatening capital and the state that facilitates it, their efforts were apparently sabotaged (http://wagingnonviolence.org/feature/repression-against-grassroots-hurricane-relief-lingers-in-new-orleans/). And speaking of the state, readers hoping for dirt about scumbag FBI informant Brandon Darby (now a conservative columnist at Breitbart, unsurprisingly), this isn’t the place. Darby gets just a few paragraphs, mostly about his rash egotism and crow’s regrets about defending him.

I would strongly recommend this book to people less familiar with anarchism and social movement history than your average well-read punk or anarchoid is. For the person in your life who thinks anarchists only wear black and smash windows, or doesn’t know who the Zapatistas are, or sees no place for the kind of armed self-defense (yes, with guns) that the immediate post-flood situation required, this is a perfect book. If you don’t know much about the grassroots efforts post-Katrina (and I didn’t), it’s a compelling read, and crow’s passion and heart comes through on every page. I don’t want to accuse crow of not writing the book I want him to have written. But for the reasons I discussed above, I think we still need another history of the CGC, one that brings us up to the present, perhaps told by Malik Rahim, crow’s comrade and former Panther who co-founded Common Ground with him. Without such a history, we have a detailed snapshot told by one man of heroic efforts in traumatic times, instead of a tool we can continue to return to for guidance in similar situations as emergency wanes and the status quo creeps steadily back in.