By R.L. Updegrove

Peace & Change

January 2018

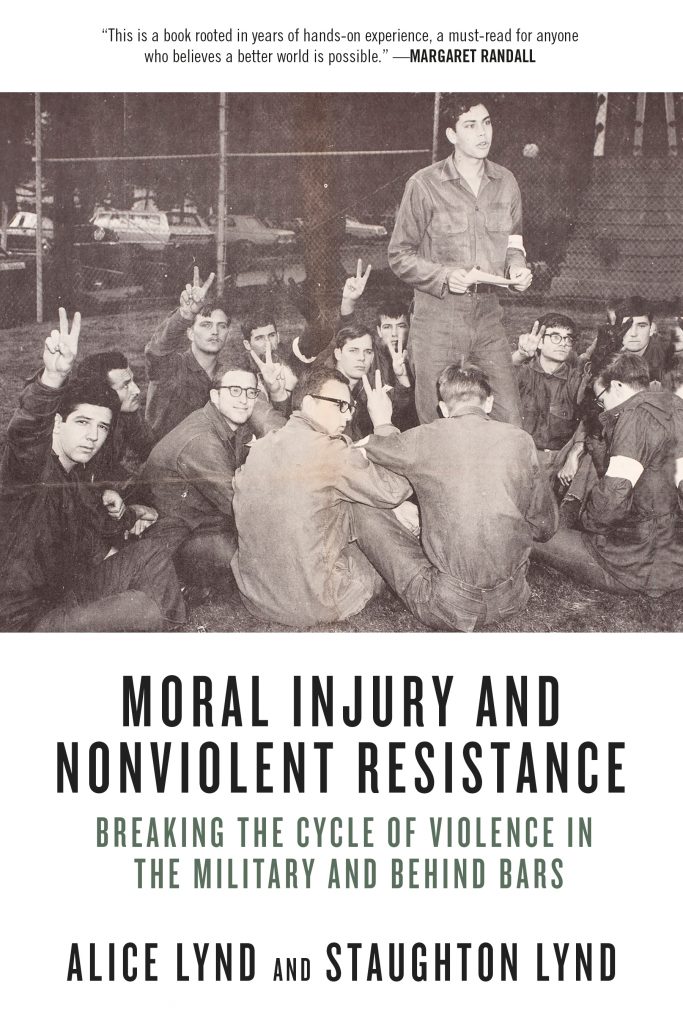

The words of Alice and Staughton Lynd in their latest study of nonviolence were poignantly reinforced this summer as two countries openly threatened each other with nuclear war and a peaceful protester was murdered during a white supremacist rally. The theme of “moral injury” resonated both in the pages of the book and in the emotions evoked by the news headlines. The Lynds attribute the phrase to Dr. Jonathon Shay, a psychiatrist with the Department of Veteran Affairs during the 1960s, who denied it as “a choking-off of the social and moral world” after doing, seeing, or failing to prevent something that “you know in your heart is wrong.” The Lynds show how moral injuries can lead soldiers to become conscientious objectors and can lead those held in solitary confinement to organize hunger strikes and create a common identity of resistance. Although the subtitled section “Behind Bars” makes up only one-quarter of the book, the similarities between the moral injuries sustained in prisons and on battlefields striking and worth further study.

The book is organized in two parts, with four chapters devoted to warfare and three chapters focused on imprisonment. The final chapter discusses the role of lawyers in nonviolent direct-action campaigns in the both the labor movement and the African American Freedom Movement. A shared theme across all chapters is a reliance on personal anecdotes from those fighting in wars and those fighting for prison reform. The Lynds allow those who have suffered moral injury to tell their own story and then provide historical and social context for those personal experiences. For instance, the second chapter serves as a concise evolution of international law from the Hague Conventions (1899 and 1907) and the Kellogg-Briand Pact (1928) to the 1984 Convention Against Torture and the establishment of the International Criminal Court which went into force in 2002. Together, these chapters tell the story of how soldiers, diplomats, prisoners, and lawyers have attempted to break the cycle of violence from the international stage to the confinement of a solitary prison cell.

The strengths and weaknesses of Moral Injury and Nonviolent Resistance: Breaking the Cycle of Violence in the Military and Behind Bars are revealed in its title and its structure. It is a dynamic concept to link the experience of soldiers and prisoners, but the preponderance of the book focuses on warfare which creates a sense that the prison chapters are an appendix. While possibly a weakness, it is also a testament to the strength of the prison chapters. They stand on their own as an inquiry into the moral injury that occurs inside prisons and provide a compelling history of the prison reform movement in Ohio, Illinois, and California. The same can be said of the final chapter of “In the Military,” which tells the story of Israeli refuseniks and includes ten pages of testimonials and statements from various groups and individuals refusing to serve in the Israel Defense Forces. the chapter is certainly connected to the previous three in its section, but it reads more as a case study than an extension of the narrative.

Alice and Staughton Lynd have created a powerful book that can be read cover to cover as a compelling way to introduce readers to the history of nonviolent direct action. Seasoned scholars of nonviolence will also gain from reading the first chapter which outlines the concept of moral injury and “Behind Bars” which details the use of nonviolent resistance in the U.S. prison system during the twenty-first century. This book continues the remarkable contribution the Lynds have made to the study of nonviolence. It could not be more timely or thought-provoking as we contemplate the repercussions of warmongering rhetoric and the empowerment of white nationalists in the United States.

Back to Alice Lynd’s Author Page | Back to Staughton Lynd’s Author Page