By Dan Salerno

Lifesomethings

May 20th, 2019

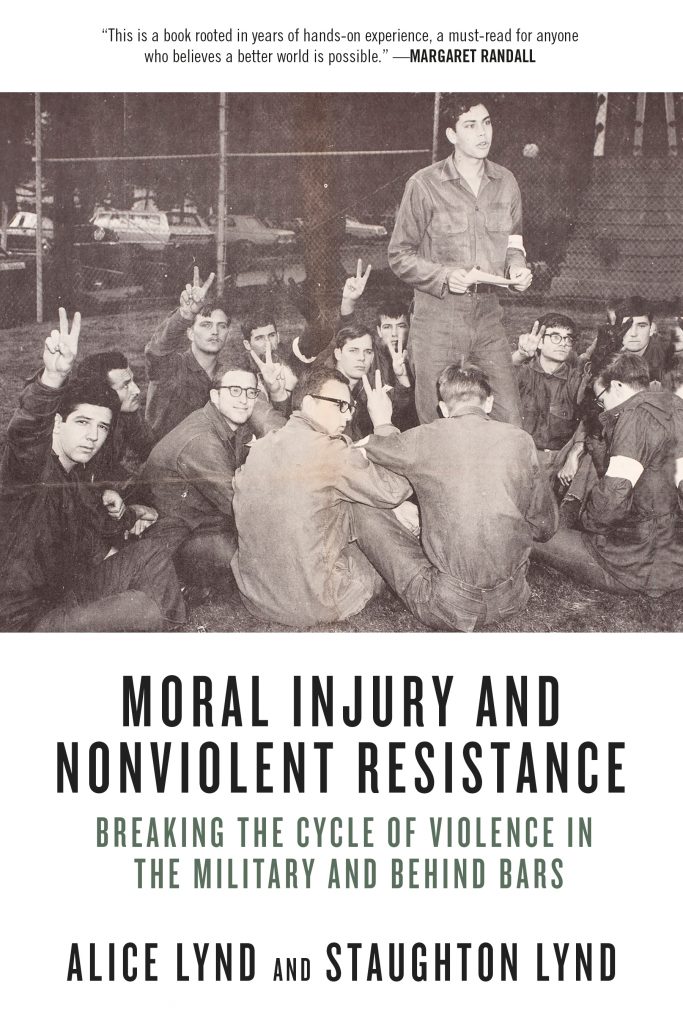

Staughton Lynd is an historian and attorney who has been a long-time activist for civil rights, labor rights, and peace. A graduate of Harvard University with a Ph.D. from Columbia, he taught at Spelman College in the 1960s, and in 1964 was invited by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to coordinate the Freedom Schools in Mississippi. He earned a JD at the University of Chicago Law School in 1976. His many books include Accompanying: Pathways to Social Change, and Intellectual Origins of American Radicalism. Alice Lynd has a JD degree from the University of Pittsburgh School of Law. During the Vietnam War she published We Won’t Go: Personal Accounts of War Objectors. Together the Lynds have edited oral histories, including the classic Rank and File: Personal Histories by Working-Class Organizers, and a memoir Stepping Stones. Prior to the third edition of Nonviolence in America: A Documentary History, their most recent book is Moral Injury and Nonviolent Resistance: Breaking the Cycle of Violence in the Military and Behind Bars. They live in Ohio.

You have been at the forefront of social justice in the US for over six decades. What continues to motivate you?

Alice: Human rights.

Staughton: I continue to abhor the institutionalized violence, the disregard for those at the bottom of the heap, the intense individualism and resultant isolation, of our capitalist society. Having lived in a small intentional community in the hills of Georgia when my wife Alice and I were in our twenties, I know there is a better way. As I accompanied the cows to the milking barn in the early morning dark, everything I could see as the sun came up over the rim of surrounding hills was part of the new way of life we were creating.

To what extent did your childhood influence your adult life?

Alice: My parents were very much concerned about world peace after World War I.

Staughton: My parents were among those pejoratively known as “fellow travelers,” that is, radicals but not Communist or Socialist Party members. My mother, as student body president at Wellesley, had protested a raucous celebration at the end of World War I and insisted on a solemn chapel service built around Kipling’s “Recessional” (“the captains and the kings depart,” etc.). My father, during a student internship between the first and second years at Union Theological Seminary, worked alongside his parishioners at a Rockefeller oil well in Elk Basin, Wyoming, preaching in the school house Sunday evening.

What is your most vivid recollection of serving as the director of the Freedom Schools during the summer of 1964?

Staughton: Probably the so-called Freedom School Convention held in the outskirts of Meridian, Mississippi in early August 1964. Each of the almost forty schools sent a couple of delegates. They debated and adopted resolutions about a long list of political issues. Most important, they wisely determined to return to their impoverished segregated schools, and improve them, rather than take a chance that our “freedom schools” could survive and provide appropriate credentials upon graduation. (See Jon Hale, The Freedom Schools, map on page 6.)

At one point the both of you combined forces for an oral history project that focused on the working class. What was the biggest take-away from that experience?

Staughton: There is a mystique that infects the work of historians of the CIO and the contribution thereto of John L. Lewis. Lewis created unions in steel, rubber, meat packing, and so on, that replicated the topdown structure of the United Mine Workers. CIO collective bargaining agreements typically contained (1) a management prerogatives clause that gave management the right to make unilateral decisions about opening and closing plants and thereby doomed our struggles in Youngstown and Pittsburgh; (2) a clause forbidding strikes, slowdowns, and other forms of direct action during the life of the contract. Takeaway: Never give up the right to strike. It is better to have no contract, and undertake shopfloor struggles one by one, than to give away labor’s only effective tool.

Alice: Coming to know some of the individuals and gain insight into their experiences: Kate Hyndman, Vicky Starr, Sylvia Woods, George Sullivan, John Sargent, Ed Mann.

You both seem to have a heart for education. Staughton, you were a professor until your return from Hanoi in January, 1966. Alice, you graduated with a degree in childhood education, did draft counseling and trained draft counselors. What was the most rewarding part of those experiences?

Staughton: I was an administrator of the Freedom Schools. As a teacher, I have most enjoyed seminars in our basement at home. We are presenting one right now on non-violence.

Alice: Coming in touch with people at the deepest level; the concept that the counselee and the counselor were two equal experts, hand in hand.

Alice, when you were growing up your family moved quite a number of times (over 40). What was it like growing up during the Great Depression? Staughton what was your childhood like?

Alice: I was aware of my parents’ struggle to make enough money. At one point, I offered to give them what I had saved from my allowance, 37 cents, but they refused. We lived at my grandfather’s house when my parents had no work. Moving so many times, it was not until I was fifteen that I had any significant friendships.

Staughton: Both my parents were full-time teachers. Our family was secure.

You both became lawyers later in life. Staughton why did you choose law? Alice, you were in your mid-fifties when you went to law school. What was that like?

Staughton: We sought a profession that would permit us to work together. For me to take a job in a steel mill would not have permitted this. So we chose law as an occupation that would make use of my flair for the big picture and Alice’s mastery of detail.

Alice: We chose to go into law with the idea that Staughton was good at working with big ideas, and I was good at working with administrative regulations in order to make a case based on essential facts and concepts. Going to law school, beginning at age 52, was at the extreme limit of what I could do. During the first semester, I was in a special course for older and/or disadvantaged students. We were taught how to write answers to essay questions on law school exams. One professor told us that we would not be there if the law school did not believe we could succeed. That was encouraging.

Alice: I loved the process of figuring out with clients what the relevant facts and contract provisions were, or what needed to be shown to comply with legal requirements. Sometimes it would be a meeting with a group of retirees and we would piece together not just what was said on paper in a contract, but how things actually worked in the shop.

Staughton: Liberation theology as developed by Latin American exponents including Oscar Romero advocated “accompaniment” rather than organizing. The organizer approaches other human beings with the intent to cause them to adopt predetermined ideas and engage in predetermined actions. In accompanying, you and I walk side by side, each learning from the other.

Alice, during the same ACLU interview you mentioned concern for mutual respect when presenting cases within the legal system. You made the point that “you don’t disrespect your adversary.” You also said that problem solving should include mutual respect and the ability to recognize there’s another side to any case. Would you care to elaborate?

Alice: Yes. This is very important to me. There isn’t any case unless there are differences that have to be overcome. The point is to resolve the differences, not call each other names. Once the adversary recognizes that we want to solve the problem and assume they do too, then we can look for a way to reconcile what they want and what we need.

In the ACLU interview, you both mentioned a carry-over of this type of respect as a crucial ingredient to a successful marriage. Alice, you said, “we’ve learned to value our differences.” Staughton, you said “if we regard these differences as alternative strengths we can be hell on wheels.” Any further thoughts on how to achieve this sort of harmony in marriage? In life?

Alice: Listen! What can I learn from the other person? From my starting point, and from his starting point, what is the third point where we can come together and be enriched by the other one’s perceptions?

Staughton: We believe in the institution of marriage. Among major activists of the 1960s about whose personal lives we have knowledge, ours is one of the few marriages to have survived that decade. A key, as we see it, is to reject the marriage in which the husband roams the world making speeches and Doing Good while the wife stays home, takes care of the children, and keeps the household from falling apart. We reject the concept of living parallel lives.

What about your faith? To what extent has your faith influenced your life?

Staughton: As a youngster I attended the Ethical Culture Schools in New York City from pre-kindergarten through 12th grade. At the 64th Street meeting house there was and is an auditorium. I graduated sixth grade and was inducted as student body president on that platform. The words above the platform were “The place where men [later modified] meet to seek the highest is holy ground.” As adults Alice and I became Quakers. There the essential concept is the belief that all human beings have an inner light, a voice of conscience. We oppose calling soldiers “baby killers” or police officers “pigs.” While firmly opposing action we believe to be wrong, we must at the same time – as it were, with the other hand – reach out and say, Join us.”

Alice: Being a Quaker has been very important to me in doing prison work. One time, a prison administrator asked me, why do you do this? I told her, because Quakers believe there is an inner light in every person; we try to reach that in these men. We oppose the death penalty. We reject the concept of life without parole as an alternative to the death penalty, because we believe people can change. Once a lieutenant said to us, “You have always respected me. Why?” We ended up with him showing us pictures of his grandchildren.

Is there anything else you’d like to mention?

Alice: It was not until after we retired that I began to feel that I had found and was able to do needed work that no one else would do. It has been very demanding, and very rewarding. I could not have done any of this without Staughton’s vision of the person I could become.

Back to Alice Lynd’s Author Page | Back to Staughton Lynd’s Author Page