By David Raimon

Lithub

April 6th, 2018

On Nature Writing, Technology, and Poetic Form

Prior to my first interview with Ursula, my wife and I were planning a hiking trip to the North Cascades National Park along the border between Washington State and Canada. But wildfires, the new summer norm in the Pacific Northwest, had another idea, shutting down the park and sending us scrambling for last-minute alternatives. I knew of Ursula’s long-standing love of Steens Mountain in the remote high desert of the farthest corner of southeastern Oregon, a landscape that had informed the world of her novel The Tombs of Atuan, as well as her poetry-photography collaborative collection Out Here. Even though we had yet to meet, I decided to call her up and see if, by chance, she had any suggestions to save our vacation.

“Do you know about dark skies?” Ursula asked, clearly excited to share. “That this is one of the only places left in the United States where you can experience true darkness, see the stars as if under a sky with virtually no light pollution?” she continued, her voice full of the wonder of countless nights under that very sky.

Soon my wife and I found ourselves “out there,” in a town of fewer than 20 people, in a hotel run by fifth-generation Oregonians, in a region where wild horses still roamed under the brightest of dark skies. “Tell them Ursula and Charles sent you,” she told us, and we were taken in and cared for by the rare breed of people who lived out there, farmers and ranchers who could trace an unbroken lineage back to the first white settlers in the region. As my wife and I sat together beneath the “blazing silence,” “the endless abyss of light,” contemplating our place in the world, in the universe, we were, unbeknownst to us, learning about Ursula through these dark skies and the people they illuminated, long before Ursula and I were to meet face-to-face.

Now, when I think of Ursula’s poetry it’s this, these unadulterated skies and the people who generation after generation have lived beneath them, I think of most. If imagination is the word that comes first to mind about her fiction, contemplation is the word I’d most associate with her poetry. She does not write science fiction poems, poems taking place in imagined other worlds, but rather contemplates our place in this one. If one removes human light from the sky, allowing it to become again “eternity made visible,” if one spends time in a land where antelope, coyote, pelicans, and raptors far outnumber human souls, certain questions of meaning inevitably arise. What does true fellowship with the nonhuman other—animals, birds, plants, the land itself—look like? What human tools and technologies, stories and language, are worth passing on generation to generation? What is our proper relationship to mystery, to wonder, to what we don’t know, to what we can’t?

Ursula’s world is not a Manichean world,

one where darkness and light are in opposition. “Yin and yang” can be

translated as “dark-bright” and for Ursula, much like in the precepts of

Taoism, these seeming opposites are actually one thing, inseparable,

interconnected, and interdependent. The people of the world of Earthsea

wrote and passed down many Taoist-like poem-songs, none older than the

poem of their own creation myth. This culture chose to pass down this

poem, generation after generation, to contemplate “dark-brightness” and

their place within it. And Ursula, fittingly, chose an excerpt from it

as the epigraph to the book that introduces their world to us, a world

that still strove for harmony and balance with otherness:

Only in silence the word,

Only in dark the light,

Only in dying life:

Bright the hawk’s flight

On the empty sky.

Each

summer since our summer in the Steens, the wildfires have worsened and

spread. The contemplation of nature is now an inevitably political

thing. As we continue to look up at a sky that has been humanized, that

reflects back our own light, our own selves, rather than that of

otherness, that no longer prompts us to pause in awe and contemplate,

the opportunities to create fellowship seem to diminish. It’s the

attentiveness of poetry, of Ursula’s poetry in particular, that enacts

ways to still do so.

–David Naimon

*

David Naimon: You’ve talked about the phenomenon that happens sometimes when you’re writing a novel, that you hear a voice, the voice of another inside of you, a voice that becomes the character that tells the story for you. I was wondering if you feel like writing poetry involves a similar voice.

Ursula K. Le Guin: Well, that’s complicated. I don’t write very many persona poems, which is the equivalent of the voice of a character dictating to you in a novel. I have written some, but poems come in their own, different way. It tends to be a few words or even just a beat, with a kind of aura about them, and you know then that there is the possibility of a poem there.

Sometimes they come very easily, but I’ve

never felt like I was taking dictation with a poem the way I have felt

with novels, like the voice speaking through me was so certain of what

it wanted to say that I didn’t have to argue.

“. . . poems come

in their own, different way. It tends to be a few words or even just a

beat, with a kind of aura about them, and you know then that there is

the possibility of a poem there.”

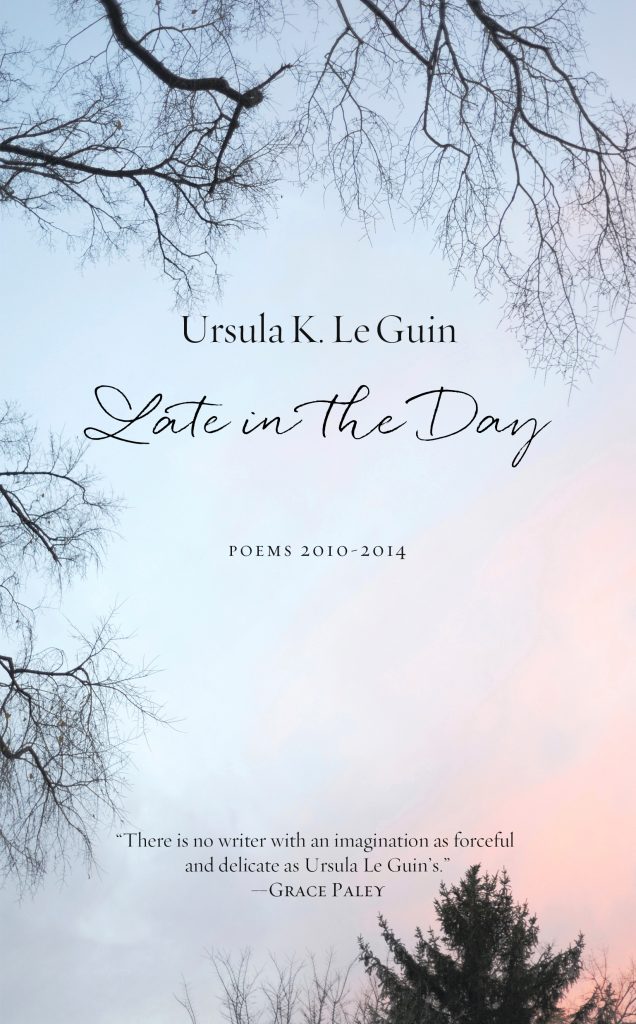

DN: I know you don’t write

haiku, but there are a lot of poems in Late in the Day that I suspected

might share a sensibility with haiku. It drove me to Robert Hass’s

introduction to The Essential Haiku to see if my instincts were true in

this regard. Hass says that haikus are attentive to time and space, that

they are grounded in a season of the year, that the language is kept

plain with accurate original images drawn from common life, and that

there’s a sense of the human place within the cyclical nature of the

world. Do you recognize those qualities in your poems?

UKL: Yes, I feel totally at home with that. The thing about haiku is the form doesn’t work for me in English. I don’t think syllabically, I think rhythmically. The syllable count just doesn’t give form to me. That’s a shortcoming in me, not in the form, so my equivalent of the haiku is the quatrain, which is, of course, a very old English form, with mostly iambic or trochaic rhythm, and often with rhyme.

DN: Are there some particular examples of poets who write in quatrains that you love?

UKL: A.E. Housman is the absolute master of the quatrain. I grew up with Housman from 12 or 13 on. He goes deep.

DN:

Booklist has a review of one of your earlier collections called Going

Out with Peacocks, and in it, the reviewer says that the book can be

divided into poems about nature from which political concerns are not

entirely absent, and other poems that are political where nature is not

entirely absent. [Le Guin laughs.]

This seems true of the poems of

Late in the Day as well. It’s interesting how, even in the nature poems

we get the sense, in the background, of either political concern or

political uneasiness. You frame this well in the foreword to the

collection, a reprint of a talk you gave at the “Anthropocene: Arts of

Living on a Damaged Planet” conference at UC Santa Cruz.

UKL: How can you write about nature now without—well, I guess we have to call it politics—but without what we have done to our world getting into the poem? It’s pretty hard to leave that out entirely.

DN: But if a reader were to skip the foreword and read some of the poems, one might think, on first glance, that there is nothing political in Late in the Day. The foreword seems to suggest that the advocacy for stillness and silence and fellowship is, in and of itself, a radical act.

UKL: Yeah, I suppose so. Yes.

DN: There are many nods in this collection to the relationship to time.

UKL: It is, after all, called Late in the Day. [Laughs.] It was written in my mid-80s, so there’s a lot about that.

DN: At various moments you say, “Time is being,” “Time is the temple,” and in “The Canada Lynx” you evoke the virtue of moving in silence through space without a track and disappearing. This sentiment feels very much akin to Taoism, to a Taoist evocation of time and space.

UKL: There is almost certainly Taoism in it, because it got so deep in me and everything I do. There’s some Buddhism, too, and of course “The Canada Lynx” is also an elegy, because we’re losing the lynxes—they are leaving quietly. So, there’s a mixed feeling there—it’s praise for being able to move quietly but also lament for the disappearance, for the going away.

DN: In the foreword you talk about the importance of fellowship with the nonhuman other. And by “nonhuman other” you are referring not just to animals and plants, but also stones and even the objects that we as humans have fashioned for our own use. Your poem “The Small Indian Pestle at the Applegate House” is a great example of this. The repetition of words—hand, held, hold—really evokes this sense of repeated fellowship, not only with the object but also with others who have used it before and with the person who originally made it. In that same speech you talk about being against the idea of the “techno-fix.” I bet a lot of people assume when they see this, a poem about a pestle, and a philosophy opposed to the techno-fix, that you are antitechnology.

UKL: Oh, yeah. I’m labeled a Luddite instantly.

DN: Can you parse that out a little bit for us? Because it seems like the pestle is a technology just as language is a technology.

UKL: Of

course it is, it’s a great technology, and it lasted us for hundreds of

thousands of years. My objection to the use of the word “technology”

these days, is that people think “technology” means “high technology,”

resource-draining technology such as we delight in. And of course, a

mortar and pestle is a very refined technology and a very useful one.

All

of our tools, the simplest tools, are technology, and a lot of them

have been perfected—you can’t improve upon them for what they do. A

kitchen knife. It does what a kitchen knife does in human hands and you

can’t beat it. You can get an elaborate machine that slices meat for you

and so on, but there you go. You’re beginning to seek the save-time or

don’t-touch-it-yourself thing that high tech leads us toward. I just

keep finding this, people saying, “You’re antitechnology.” Well, come

off it. [Both laugh.]

I write with a pen or pencil or on a computer.

That’s my job. I use technology all the time, but if I didn’t have the

computer or the pen or the pencil, I would end up scratching it on wood

or stone or something.

DN: And it feels like the quote you have from Mary Jacobus, where she says that “the regulated speech of poetry may be as close as we can get to such things—to the stilled voice of the inanimate object or the insentient standing of trees,” that perhaps this regulated speech is a form of technology also, to aid us in moving toward fellowship or contemplation.

UKL: I don’t know if you can call language “technology.” Technology is really involved with tools. Language is something we emit and we have to learn it at a certain period or we can’t. Language is strange.

DN: In that same speech you talk about your mutual love of science and poetry, how science explicates and poetry implicates. Can you talk more about this, and about your desire to subjectify the universe? I know normally, when people think of subjectification, they think of something interior, maybe even self-referential, but here you’re seeing it as a path toward reaching out.

UKL: There was an article by Frans de Waal in the New York Times about tickling bonobo apes and getting the complete, as it were, human response, of giggling, of drawing away but wanting more, and so on. A marvelous, subtle article. Many scientists want to objectify our relationship with animals and so we cannot say that the little ape is acting just the way a little human would. No, it’s responding only in ape fashion. We mustn’t use human words, we mustn’t anthropomorphize. And as de Waal points out, there’s this kind of terror of fellowship. We can’t, we’re not to, have fellow feeling with an ape or a mouse. But where’s poetry without fellow feeling?

DN: You have a poem, “Contemplation at McCoy Creek,” that deals with this issue of subjectifying the universe, of reaching outward, really well.

UKL: It’s a kind of philosophical poem, and I will say a word about it. I was out in Harney County without a library, wondering what the word contemplation means. It seems to have the word temple in it, and the prefix con means “together,” you know. So that is where I started, and then—this will explain the middle of the poem—there was a book in the ranch house, a kind of encyclopedia-dictionary, and it had a very good essay on the word contemplation. So it was sort of a learning experience, this poem.

DN: There is a line at the beginning of that poem—“seeking the sense within the word”—that reminded me of something you said in an interview with Poetry Society of America. They had a column called “First Loves,” where they asked poets to talk about their first exposure to poetry. You talked about a collection of narrative poems, Lays of Ancient Rome by Thomas Babington Macaulay, and also about the poems of Swinburne, how you learned through those poems that you could tell stories through poems, but also that the stories are often beyond the meaning of the words themselves, that there is a deeper meaning of story that comes from the beat and the music of the words, not from the meaning of the individual words. Can you talk about that a little bit?

UKL: That deeper meaning is where poetry

approaches music, because you cannot put that meaning in words in an

intellectually comprehensible way. It’s just there and you know it’s

there, and it is the rhythm and the beat, the music of the sound that

carries it. This is extremely mysterious and rightly so.

“That

deeper meaning is where poetry approaches music, because you cannot put

that meaning in words in an intellectually comprehensible way.”

DN:

Robert Frost talks about it, or compares it to hearing somebody having a

conversation on the other side of the wall. You’re able to tell what

they’re saying through their intonation and their rhythm, but you don’t

actually hear any of the individual words.

UKL: You can tell what they’re feeling, but you may not know really what they’re talking about. You know how they feel about it by the sound—yeah, that’s neat.

DN: When we last spoke, you also mentioned this with regard to Virginia Woolf, who I know didn’t write much poetry. Is that a similar phenomenon, do you think, what you learned when you were young with poetry, around the meaning of the sound, and what you’ve described of the meaningfulness of Woolf’s relation to sound when you write prose?

UKL: When you’re talking about the sound in the rhythm of prose, it is so different from poetry, because it’s in a way much coarser. It’s a very long beat, the rhythms of a prose work. Of course, the sentence has its rhythms too. Woolf was intensely aware of that. She has a paragraph about how rhythm is what gives her the book, but, boy, it’s hard to talk about. It’s one of these experiential things that we don’t really have a vocabulary for. I wonder if there is a vocabulary for it. It’s like talking, again, about music. You can only say so much about music and then you simply have to play it. Some person can hear it and get it or not get it.

DN: Who are some of the poets that you love as an adult? Your cherished poets?

UKL:

I have to put Rilke very high. I had MacIntyre’s translation of The

Duino Elegies one summer when I needed help. I was in a bad time, and I

kind of feel like some of the elegies got me out of it. They carried me

through it, anyway.

I don’t know German. So, Rilke and Goethe I have

to get with facing translations and then just work my way back and

forth and back and forth. Usually I end up trying to make my own crummy

translation, so I can work my way into the German words with a

dictionary. That is a very laborious way of reading poetry, but boy if

you do it word by word, if you don’t know the German nouns and have to

look up every single one, and the verbs are mysterious and not in the

right place [laughs], by the time you’ve done that, you know the poem.

You’ve kind of made your own version of it in English, and that’s why I

love translating from languages I do know and even from languages I

don’t, like with Lao Tzu.

DN: You also wrote the preface to Rilke’s Poems from the Book of Hours when New Directions

rereleased it.

UKL: Actually The Book of Hours is not one of my favorites. I like later Rilke. He’s a very strange poet and a lot of what he says doesn’t mean much to me. But when he says things and it’s the music, even I know. My father was a German speaker, and I heard him speak German, so I know what it sounds like even if I don’t know the language. It’s the music that carries it in reality. A strange rhythm he has.

DN: Can you talk about your attraction to translating Gabriela Mistral? You dedicate one of the poems in Late in the Day to her. What was it that you fell in love with?

UKL: It was not exactly love at first sight. I

didn’t know very much Spanish when I started reading her. My friend

Diana Bellessi in Argentina sent me some selected Mistral and said, “You

have to read this,” and so I labored into it with my Spanish dictionary

and I just fell in love. I never read anything like Mistral.

There

isn’t anybody like Mistral, she’s very individual, and it’s an awful

shame that Neruda—the other Chilean who got the Nobel—gets all the

attention. But you know men tend to get the attention and you sort of

struggle to keep the women in the eye of the men. Neruda is a very good

poet, but Mistral just has a lot more to say to me than he does.

DN: And what about the endeavor of translating when you come back to your own writing? Do you feel like you can trace influences from the efforts of translation?

UKL: Oh, yeah. I can trace influences from individual poets and think, “Oh, I’m trying to do Rilke here, don’t try that!” [Both laugh.]

DN: I really loved the afterword to Late in the Day entitled “Form, Free Verse, Free Form: Some Thoughts,” where you talk about your long-standing poetry group, and also about the realization you had, from doing the poetry group assignments, that form can give you a poem. By that you don’t mean to say that just by following the rules you’re going to get a poem. You mean something else.

UKL:

This is touching back on that same mystery of form, rhythm, and so on.

This is something that I think is clear to many poets, but I was very

slow to realize it. By committing yourself to a certain form—let’s say a

really complicated one, like a villanelle, which seems very artificial,

and unbelievably difficult when you first approach it—certain lines are

going to have to repeat themselves at certain intervals and you don’t

fiddle with that. If you write a villanelle, by golly, you write a

villanelle. You don’t write something like it and call it a villanelle.

Take the rules seriously and somehow or other, as you follow them, you

find that the necessity of having to do something gives you something to

do. I don’t know how that works, and it doesn’t always work.

The

sonnet is probably the form most people think of when you talk about

poetic form, and I find them terribly difficult. I write very, very few

anymore. Maybe because there are so many very very good sonnets. I don’t

know, that doesn’t usually worry me. It’s just not a form that I work

with very well. The quatrain, on the other hand, is a straight form in a

way—just four lines, that’s it. There’s no other definition, but you

can make it just as strict as you please with rhythm and rhyme and so

on.

I think any artist in any medium will tell you the same

thing, that if you’re working toward a certain form, whether you

originated it or it’s something you inherited from other artists, you

have complete freedom there. In a way, I find metric rhyming verse gives

me more freedom than free verse. It’s a different kind of freedom.

“By

committing yourself to a certain form. . . certain lines are going to

have to repeat themselves at certain intervals and you don’t fiddle with

that. If you write a villanelle, by golly, you write a villanelle.”

DN:

It reminds me of the fellowship with the pestle again, in a way. If you

submit to a form, you’re also entering a conversation with a history

around the form as well.

UKL: There is that, yes, and that’s exciting, although you can’t think of it while you’re writing, because that would be scary.

DN: You said in your Paris Review interview that, in fiction writing, you could also look at genre as a form, that sometimes by choosing to adopt a form in fiction, you will also discover things that you wouldn’t have otherwise.

UKL: Absolutely. I think anybody who tries to write in genre seriously, who isn’t just using it because it’s chic at the moment or they think they could do better than hack writers, they find that “Oh, I have to do it this way, so how do I do that?” There’s a sort of commitment there that makes you take it seriously. It opens up evidence to you that you would not have thought of by yourself, that the form hands over to you. But again, it’s hard to describe.

DN: I’m curious about the absence or the relative absence of science fiction and fantasy in your poetry. . .

UKL: I can’t put them together. There is a Science Fiction Poetry Association, and some poets that I grew up with, like Tennyson, were very good at doing a kind of science fictional poetry or putting science into their poetry. My mind apparently won’t come together there. They’re different businesses to me.

DN: In the afterword to Late in the Day, you talk about free form and free verse and how you do both. Can you talk more about free form? You mention Gerard Manley Hopkins as an example of someone taking a given form but altering it.

UKL: If you are a great enough poet you can make a curtal sonnet out of the sonnet. Sometimes I wonder about Gerard Manley Hopkins. I’ve never understood his sprung rhythm. I’ve tried and tried and tried. It doesn’t make sense to me and I’m not quite sure that a curtal sonnet is a sonnet, but it’s a lovely form. That was one of our assignments in my poetry group. I had to write one. I was terrified. [Both laugh.]

DN: I looked up the definition of a curtal sonnet and was quickly lost in the terminology of it. It is an 11-line poem, but it consists precisely of three-fourths of the structure of a Petrarchan sonnet shrunk proportionally.

UKL: Yes. [Both laugh.] That’s kind of a complex way of doing it, but yeah, and it has this very strange short last line. The rhyming is fairly complex, and that description didn’t say that it’s also broken into six lines and then five lines. There is a break, and that is similar to the classic sonnet, which has that turning in the middle.

DN: When you received the National Book Foundation Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters in 2014, you gave both a beautiful and blistering speech about the commodification of art versus the practice of art. A speech that became an immediate viral sensation.

UKL: That was my 15 minutes, my whole 15 minutes. That was so amazing, when I woke up the next morning.

DN: You end Late in the Day with a transcript of this speech. In it you say that resistance and change often begin in art, and that most often it is in the art of words that you see the beginnings of resistance and change.

UKL: After all, dictators are always afraid of poets.

This seems kind of weird to a lot of Americans to whom poets are not

political beings, but it doesn’t seem a bit weird in South America or in

any dictatorship, really.