By Zadie Smith, author of White Teeth

Harper’s Magazine

October 2011

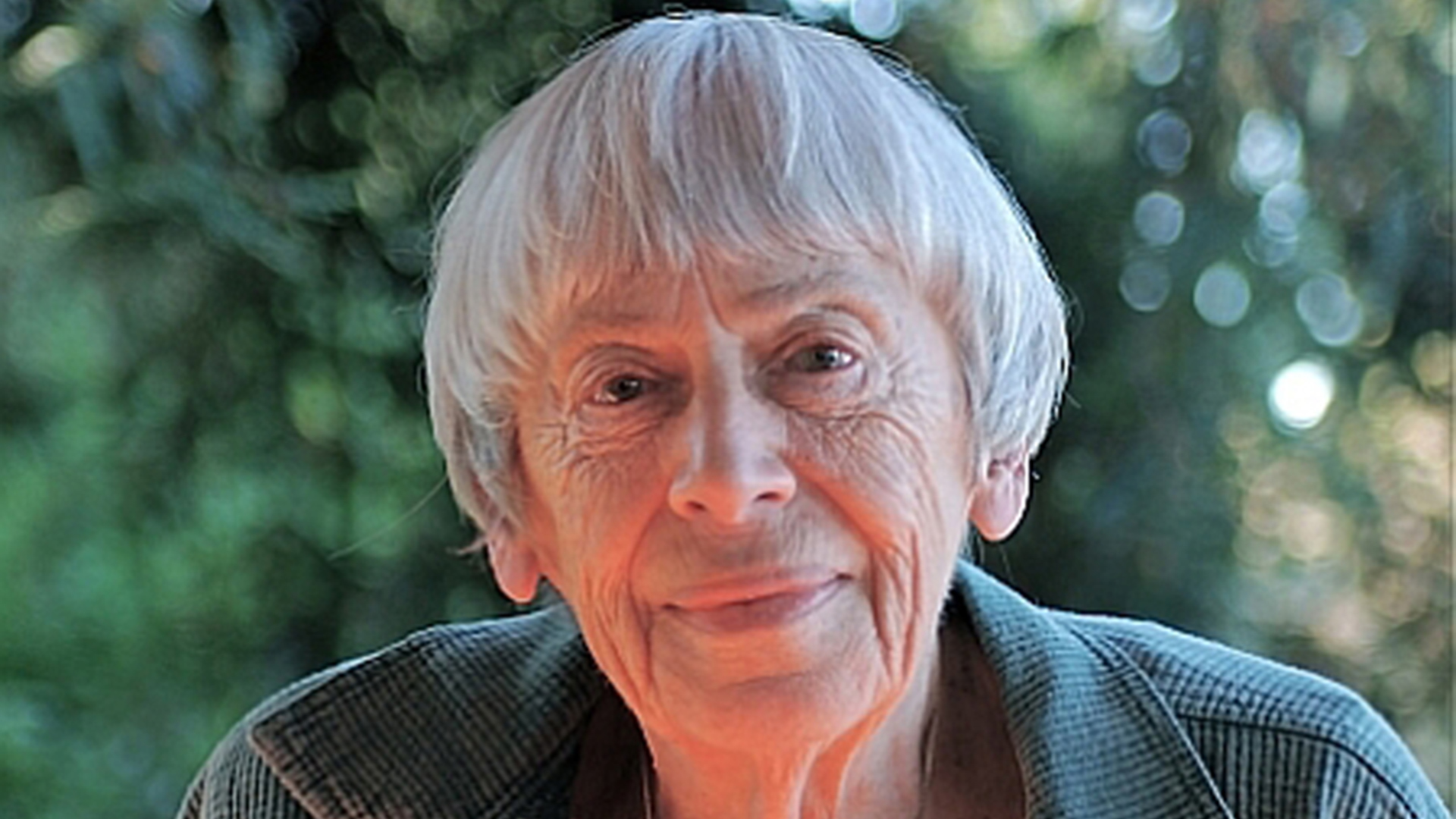

The two best books I read this month—The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed—are far from new, published in 1969 and 1974, respectively. Their author is now eighty-one years old. Trying to describe their majesty, I feel like one of Ursula K. Le Guin’s intergalactic interlopers taking her first step on alien soil—I haven’t been so taken with an ulterior reality since I closed the wardrobe door on Narnia. It’s not often that we finish a novel with the thought “What is gender, anyway?” or “What does it really mean to own something?” But these feats of anthropological Verfremdungseffekt are what Le Guin (herself the daughter of an anthropologist) achieves, with her unclassifiable inhabitants of the planet Winter (who grow genitals only during acts of passion, known as “kemmering”). Or her anarchist-cooperative Odonians, natives of Anarres, who possess no concept of either ownership or hierarchy. Le Guin’s The Wild Girls (PM Press, $12) is a slim publication containing one story, an interview, a few short poems, a brief meditation on the virtues of modesty, and an angry essay about corporate publishing, “Staying Awake While We Read,” previously published in these pages. The poems are underwhelming (“The Next War”: “It will take place/ it will take time/ it will take life/ and waste them”), while the essays and especially the interview are zingy and pugnacious (“The only means I have to stop ignorant snobs from behaving towards genre fiction with snobbish ignorance is to not reinforce their ignorance and snobbery by lying and saying that when I write SF it isn’t SF, but to tell them more or less patiently for forty or fifty years that they are wrong to exclude SF and fantasy from literature, and proving my argument by writing well”). The strongest reason to pick up The Wild Girls, however, is its Nebula Award–winning title story, a tale of master-slave culture on a strange planet. Here we find the City, where Crown people live; meanwhile, down in the country, the Dirt people subsist. The Dirt people are an oppressed nomad tribe. Sometimes Crown men go on forays into Dirt country to kidnap wild girl-children and bring them back to the City to be used as slaves or else cultivated as concubines. The City world has inscribed codes of conduct—ways of eating, sleeping, dancing, speaking—the intricacy of which would suffice for a cycle as long as Le Guin’s own Earthsea series, yet somehow she sums up this complex community in a handful of pages.

“Show, don’t tell,” goes the worn-out workshop mantra: Le Guin shows us how. She never recites long lists of terminology or boring (to me) Tolkienesque genealogies. Her worlds are simultaneously factitious and naturalistic—we wander in and find them fully formed, populated by characters deeply embedded in imaginary habitats:

In the evening they came to the crest of the hills and saw on the plains below them, among watermeadows and winding streams, three circles of the nomads’ skin huts, strung out quite far apart. . . . The children were spreading out long yellow-brown roots on the grass, the old people cutting up the largest roots and putting them on racks over low fires to hasten the drying.

When these worlds come under attack, we feel the violence personally, not least because Le Guin writes as well as any non-“genre” writer alive:

One little girl fought so fiercely, biting and scratching, that the soldier dropped her, and she scrabbled away screaming shrilly for help. Bela ten Belen ran after her, took her by the hair, and cut her throat to silence her screaming. His sword was sharp and her neck was soft and thin; her body dropped away from her head, held on only by the bones at the back of the neck. He dropped the head and came running back to his men.

Read the rest of the review at Harper’s Magazine HERE