By Bill Berkowitz

Daily Kos

October 22nd, 2014

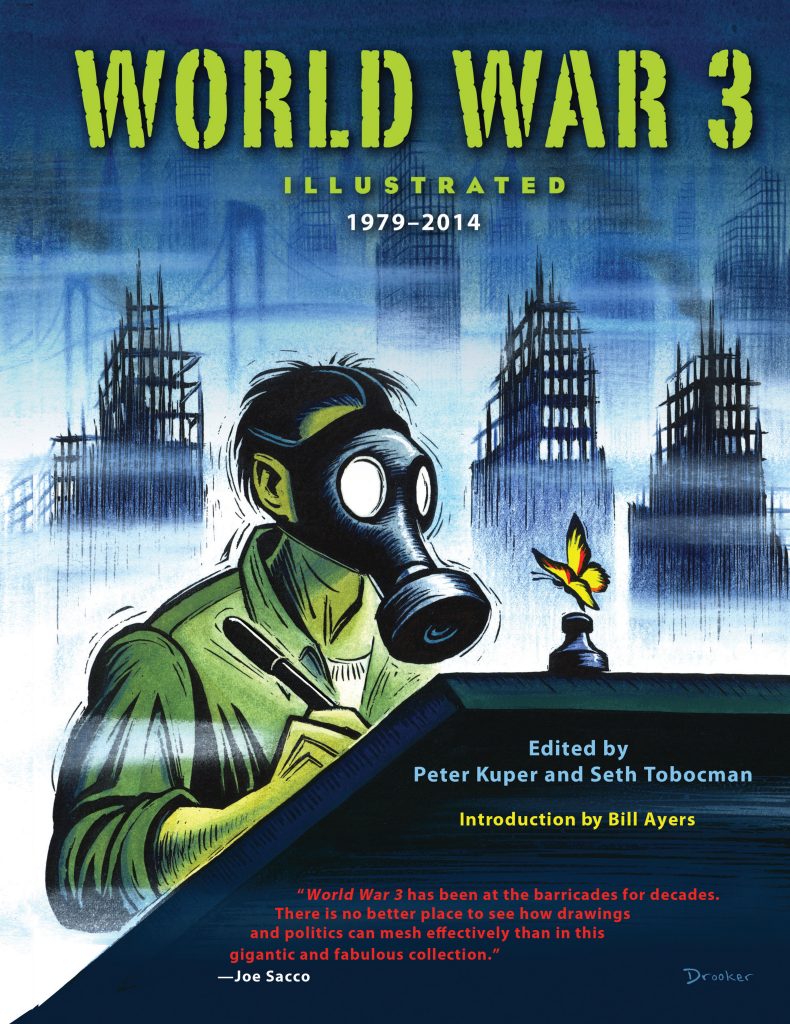

World War 3 Illustrated: 1979-2014 — Thirty-Five Years of Bashing Stereotypes, Tearing Down Walls, Smashing Icons and Visionary Cartooning

In 1979, in the wake of a meltdown at Three Mile Island, the founding of the Moral Majority by the Rev. Jerry Falwell, the murder of gay politician Harvey Milk in San Francisco’s City Hall, the Iranian hostage crisis, and the impending election of Ronald Reagan, Seth Tobocman and Peter Kuper, two art students at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, decided the time was ripe for an anti-war comic book.

In 1938, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, two guys from Cleveland, had revolutionized comic books with the publication of a story called “Superman: Champion of the Oppressed,” in Action Comics #1. Forty-one years later, Tobocman and Kuper, who grew up in Cleveland and knew each other since the first grade, were ready to create a home for political comics, graphics and stirring personal stories.

Tobocman and Kuper constructed a relatively simple, yet monumentally difficult game plan: Develop an outlet for their own work that emphasized their politics; and, create a space for like-minded artists and politicos whose voices needed to be heard. And, of course, make enough money to keep the presses rolling.

“The undergrounds were mostly gone and the alternative movement didn’t exist yet. Since we’d done zines, the idea of self-publishing wasn’t remote. Beyond publishing our own work we also wanted to print work that moved us — much of it was on the street posted on walls and lampposts,” Kuper said in a recent interview posted at comicbookresources.com. “It was work that was talking about our reality in 1979 with a hostage crisis in Iran, the Cold War in full swing and a B-actor about to have his itchy trigger-finger on the nuclear launch button.”

It is now thirty-five years later and the Oakland, California-based PM Press has just published a elaborately designed full-color anthology titled World War 3 Illustrated 1979-2014 (PM Press, July 2014, 328 pages, $29.95). The collection contains creative, hard hitting, and issue-oriented content, covering such subjects as police brutality, feminism, the environment, religion, political prisoners, housing rights, globalization, and depictions of conflicts from the Middle East to the Midwest.

In their Editor’s note, Tobocman and Kuper point out that once they began publishing their magazine, “all sorts of people were drawn to that banner: punks, painters, graffiti writers, anarchists photojournalists, feminists, squatters, political prisoners, and people with AIDS.”

The comic book: From the 1930s through the golden age of the 60s & 70s

Flash back to the mid-1950s: Raye Ellen, one of my downstairs Bronx apartment building neighbors, set-up a comic-book lending library. The process was simple; file out an index card with your name, phone number and apartment number; choose the comic books you wanted to borrow; list them on your index card; and, take them home for up to two days. If you didn’t return the comics on time, there’d be no more comics.

It’s been a long time since I’ve been a dedicated a comic-book fan. These days, I read the San Francisco Chronicle’s Sunday Comics section and its two pages of comics just about every day.

Over the years, I’ve read and reviewed a handful of graphic novels and graphic journalism. The late Bob Callahan, who edited several cartoon anthologies, most notably The New Smithsonian Book of Comic-Book Stories from Crumb to Clowes (2004), taught me a lot about the history and value of comics.

In his Introduction to The New Smithsonian Book of Comic-Book Stories, Callahan discussed the rise of America’s comic book industry: “The current era in American comic-book history swung boldly into place one brilliant San Francisco morning the late 1960s when and odd-looking man [Robert Crumb] … began to sell his own self-published comic book, Zap Comix. …The comic book itself was only about thirty years old when Crumb came along and rearranged it.

“The format first came to life in the 1930s, when the larger newspapers found a cheap way to repackage their most popular daily serials inside these new pulp pages.” The “real breakthrough” took place in 1938, “when a couple of Jewish American high school students from Cleveland, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster,” published Action Comics #1, which contained a story called “Superman: Champion of the Oppressed.” (For more, see “Superman Co-Creators

Jerry Siegel & Joe Shuster Discuss The Man Of Steel’s Origins [Video]” @ http://comicsalliance.com/….) Siegel and Shuster began to create a series of adventure stories, which transformed the industry.

Comic books about fighting the Nazis and Japanese during World War II – read by millions heading off to war — were a new development as “Over the years, the comics more often responded to the spirit of disorder — to the divine virtues Sedition, Anarchy and Mischievous – than to the need to put anybody’s house back in order.”

Many modern-day comic-book illustrators and writers stand on shoulders of Harvey Kurtzman, who is known for his “pioneering antiwar stories,” and brilliant “send-ups and parodies that made MAD Magazine the most celebrated comic of all time. Kurtzman stood up against Senator Joseph McCarthy’s anti-communist witch-hunts.

In 1954, The Comics Code Authority, a result from of almost daily newspaper tirades “connecting crime comics to juvenile delinquency,” led to publishers dumbing down the comic book. A seal on a comic book’s cover stating “Approved by the Comics Code Authority,” was aimed at protecting America’s youth from smut, profanity, obscenity, and/or communism. Comics were forced underground, and, according to Callahan, “it was twelve years … before open, smart, and adventurous comics surfaced again.”

By the mid-1960s, alternative newspapers

across the country “threw open their doors to certain new and radical

perspectives in art and politics.” From New York’s Lower East Side to

San Francisco, from Crumb’s Zap Comix to artists such as Bill Griffith,

Rick Griffin, Frank Stack, and Joel Beck, young artists and illustrators

pursued their passion with a free hand and, well … an unbridled

passion. Through the work of Justin Green, Spain Rodriguez, Gilbert

Shelton, Kim Deitch, Carol Tyler and Harvey Pekar, “the undergrounds

discovered their own literary destiny.”

Stan Lee’s brigade of

Marvel superheroes, — the Fantastic Four, Spider-Man, the X-Men, and so

many others – led Marvel to “become the most popular comic book company

in the world.” Art Spiegelman’s brilliant Maus, “which dealt with his

father’s tortured memories of life in Hitler’s concentration camps,” won

Spiegelman a Pulitzer Prize.

World War 3 Illustrated: “Honest and rowdy, boisterous and straight-forward”

Peter

Kuper told comicbookresources.com that when he and Seth Tobocman

arrived in New York, they “were still fans of comics and had become

serious about creating them, but there were few venues to get our work

published.”

Seth Tobocman was “spurred” on by the Iran hostage crisis: “I knew a lot of Iranian students who were at school with me. So I knew about how the Shah of Iran was put in by the US and how my Iranian friends were afraid of the Savak, the Iranian secret police, even while walking around NYC. So when the Shah fell and Iranians took over the US embassy, I understood why they did that. But for many Americans this was an outrage, like 9/11, and there was this wave of patriotic hysteria. So I felt, if all these ignorant people can express themselves, so could I. I decided to throw my hat in the ring.”

Both Kuper and Tobocman are accomplished artists. Kuper has produced more than 20 books and his work has been featured in Time, The New York Times, and MAD Magazine, for which he has written and illustrated SPY vs SPY since 1997. Tobocman is the author of five graphic books and he has participated in exhibitions at ABC No Rio, Exit Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the New Museum of Contemporary Art.

World War 3 Illustrated 1979-2014 is a beautifully crafted full-color anthology that is not solely politics: there are personal stories about life, death, love, hate, growth, stagnation, and the horrible loneliness of staking out positions you believe to be right.

Bill Ayers, the 1960s radical, co-founder of the Weather Underground, and a respected educator and author, who is perhaps best known for being the “pal” in Sarah Palin’s oft-repeated 2008 Presidential Election meme about Barack Obama “Palling around with terrorists,” writes in an Introduction titled “In Cahoots!”: “The artists of World War 3 have forged a space by turns harsh and exciting, honest and rowdy, boisterous and straight-forward, always powered by the wild and unruly harmonies of love. It’s a space where hope and history rhyme, where joy and justice meet. Their voices provoke and sooth and energize.”

As you read through this strikingly designed book, one cannot can’t help but admire those many young, often obscure and struggling courageous comic book artists and cartoonists who, with unbridled passion, took on unpopular issues, bashed stereotypes, tore down walls, and smashed icons.

As Kuper and Tobocmen point out in their Editor’s note: “In many ways WW3 represents a microcosm of the type of society we’d like to see — a place where people of various backgrounds, sexual orientations, and abilities pull together to create something that benefits the whole.”

With Iraq in chaos and the same tired and discredited voices trucked out by the mainstream media, a surveillance state run amok, income inequality continuing to peak, prison privatization, climate change, unabated gun violence, and Tea Party madness, it’s important to have sharply honed, no bullshit, critical perspectives to mainstream blather. World War 3 Illustrated contributors, new and old, are now hard at work cooking up their next issue.