By Scott Borchert

The Indypendent

November 17, 2010

Near the end of Terry Bisson’s utopian novel Fire on the Mountain, one character, Yasmin, receives a book of alternative history. Titled “John Brown’s Body,” the story is as absurd as it is unsettling. The militant abolitionist Brown fails in his raid on Harpers Ferry and is captured and executed; after a brief civil war, the U.S. capitalist class unites, conquers much of the continent, and gradually asserts its influence over the entire planet. War, exploitation and oppression follow.

Yasmin’s daughter, Harriet, shivers and says, “That’s why I don’t like science fiction. It’s always junk like that. I’ll take the real world.”

After all, she knows better: Brown and his

co-commander Harriet Tubman didn’t fail at Harpers Ferry in 1859 but

successfully escaped into the Blue Ridge Mountains. There they launched

the Army of the North Star, and night after night, their enormous

bonfires could be seen raging high on the mountaintops, calling others

to join the guerrilla war against slavery. And join they did — from

enslaved Africans to white abolitionists, from Italian and Mexican

republicans led by Giuseppe Garibaldi to English workers led by Karl

Marx. What began as an anti-slavery struggle developed into a war for

independence and Black self-determination, and, eventually, the land

south of the Mason-Dixon line became a new nation, Nova Africa. Not long

after, Nova Africa embarked on the road to socialism. And 100 years

later, in Harriet’s “real world” of 1959, Nova Africa’s neighbor to the

north, the U.S.S.A., has followed.

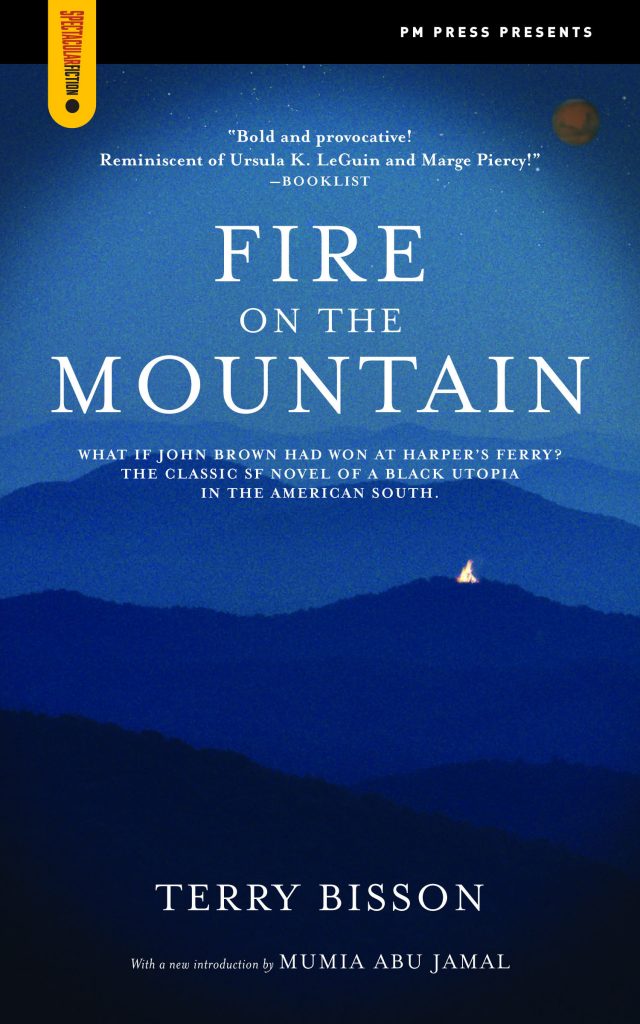

This is the premise of Bisson’s Fire on the Mountain,

released in a new edition by PM Press. Al-though originally published

22 years ago in France as Nova Africa, it is a book that continues to

provoke questions about how and why our world is the way it is — and how

it might be different.

Bisson relates his alternate version of

history through several perspectives: the written testimonial of a

teenage slave who joins Brown and Tubman’s army; the letters of a white

abolitionist doctor who is radicalized by the uprising; and a

third-person narrative that follows Yasmin and Harriet in 1959 as they

bring the aforementioned testimonial (written by their ancestor) to

Harpers Ferry on the centennial of the raid. Such a structure suggests

that history itself is better understood as a multiplicity of

narratives, generated by the distinct but interwoven experiences of many

people as they navigate the shared, fundamental contours of their

world. Bisson’s technique allows us to glimpse these fundamental

contours — slavery and capitalism, war and revolution, socialism and

national liberation.

In his introduction, Mumia Abu-Jamal praises

the vision of this novel as “one born in a revolutionary, and

profoundly humanistic, consciousness.” Indeed, there is something

revolutionary about re-imagining the past, turning history inside out

and extracting visions of a different world. Fire on the Mountain

does all of this in a way that is engaging and often inspiring — but

this is no mere exercise in radical fantasizing. Rather, by considering

what has been, and creating a narrative of what could have been, Bisson

reminds us that what is yet to come remains unwritten.