Bisson’s Fire on the Mountain: alternate history in which John Brown wins at Harper’s Ferry

By Cory Doctorow

BoingBoing

July 28, 2010

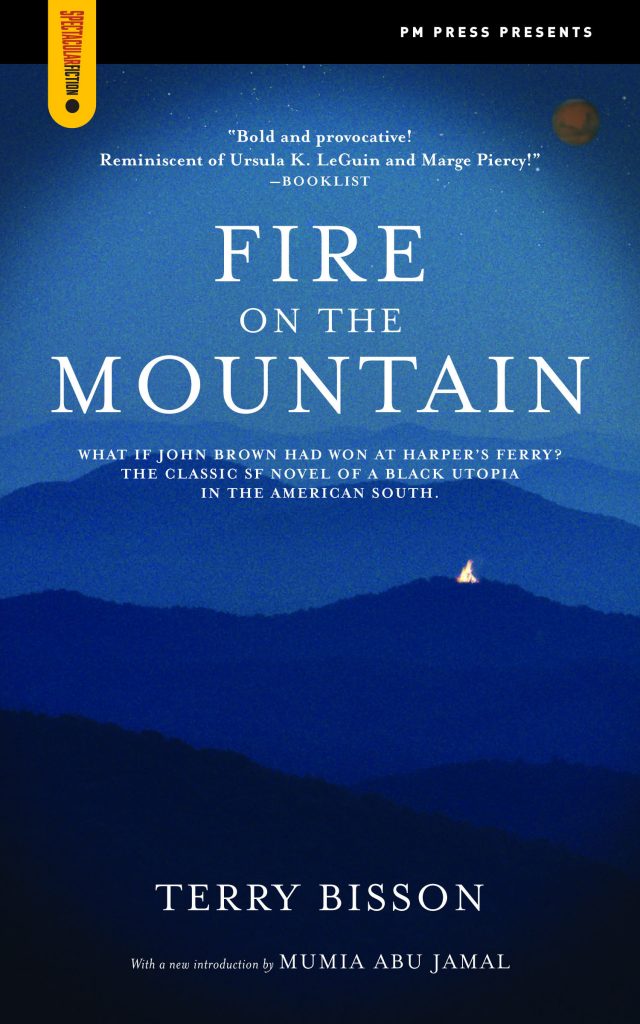

I thought of sf writer Terry Bisson’s work as being delightfully absurdist, always moving but never solemn, but then I read Fire on the Mountain, his acclaimed 1988 short novel, reprinted in 2009 by PM Press in a handsome pocket edition with an introduction written by the revolutionary Mumia Abu Jamal from his cell on death row. Now I know that Bisson is perfectly capable of being as solemn as a funeral, and that when he takes on that mode, he is just as moving, and sweetly sad in a way that reveals the powerful mastery that’s hidden behind his whimsy in stories like They’re Made of Meat and Bears Discover Fire.

Fire on the Mountain

is an alternate American civil war history, in the classic mode: one

battle goes differently, for the want of a battle the war is lost, and

the nation becomes an altogether different place. But Bisson’s approach

is more than a bit of militaristic speculation: it is a revolutionary

polemic clothed in an exciting and moving adventure story. In Bisson’s

world, Harriet Tubman joins John Brown at Harper’s Ferry and the two of

them kindle a nationwide abolitionist uprising that sparks a global

series of socialist revolutions, in Canada, Haiti, Mexico, France,

England, Ireland, and across the American continent among indigenous

people.

The story takes place in two timelines: the history

of the revolution is told in the form of a memoir of a slave-boy who

grew up to be a revolutionary leader, and in correspondence from a

white Virginian doctor who turned his back on privilege and fought

alongside the rebels in John Brown’s army.

Then there’s a

“contemporary” story, set in 1959, when socialist Africa is just about

to land its first astronauts on Mars. Yasmin is the great-great

granddaughter of the ex-slave whose memoir recounts the history of the

revolution, and she is the widow of an African astronaut who died in

space on an earlier, failed Mars mission. She is delivering her

ancestor’s papers to a revolutionary museum, travelling cross-country

with her teenaged daughter, Harriet, the bother of them absorbed with

bitter emotion at all the space travel in the news.

Weaving

between these three stories, Bisson paints a picture of a world where

progress is based on peace, not war, cooperation, not competition. And

he tells the gripping tale of the war that was fought and the blood

that was shed to get to that world, and of the ambivalence that the

fighting and the not-fighting engender among all concerned.

It’s

a slender novel, a mere 150 pages, but it does the science fiction

trick of making you step back from your own world and see it more

clearly, and it does so while wrenching your heart and setting your

pulse pounding. All in all, one of the best alternate histories I’ve

read — and a side of Bisson (a southerner who fought in the John Brown

Anti-KKK League) I’m glad to have discovered.