By Kevin McCloskey

CommonSense2 Journal

April 2010

As a kid, my favorite part of Mad Magazine was a miniature comic relegated to margins called Spy vs. Spy. For years the dueling spies were drawn by the late, great, Cuban cartoonist, Antonio Prohias. Since 1997, Spy vs. Spy has been drawn by Peter Kuper. Prohias’s Cold War satire was literally, and metaphorically, a black and white affair. Kuper has maintained the classic spies’ wide-brimmed hats and their manic energy, but he’s added shades of gray to the endless duel. Kuper’s gritty shadows look as if they were stenciled on the page with a half-empty can of spray enamel.

Kuper is a writer, educator, graphic novelist, and successful illustrator. His best known works include a graphic novel version of Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis and the award-winning children’s book, Sticks and Stones. He’s done covers for Time and Newsweek and won a gold medal from the Society of Illustrators in 2004. He was also among the first cartoonists to draw a comic strip for the New York Times.

At the top of his game in July, 2006, Kuper decided to take a sabbatical. Few illustrators, apart from those who are also academics, take sabbaticals. His father was a university professor, however, and Kuper had fond memories of living abroad during his dad’s sabbatical year.

He chose the beautiful city of Oaxaca, Mexico for its colonial charm and history. He also wanted his nine year-old daughter, Emily, to be immersed in another culture. He had no idea Oaxaca would be convulsed by strikes, barricades, riots, mayhem, then a crackdown by the ‘federales’ that would leave at least 20 protesters shot dead.

“I wasn’t looking for trouble. On the contrary, I was hoping for some escape. Escape from the United States under Bush’s administration, escape from my workaholic schedule, escape from the consumer culture and a ceaseless barrage of depressing news stories. ”

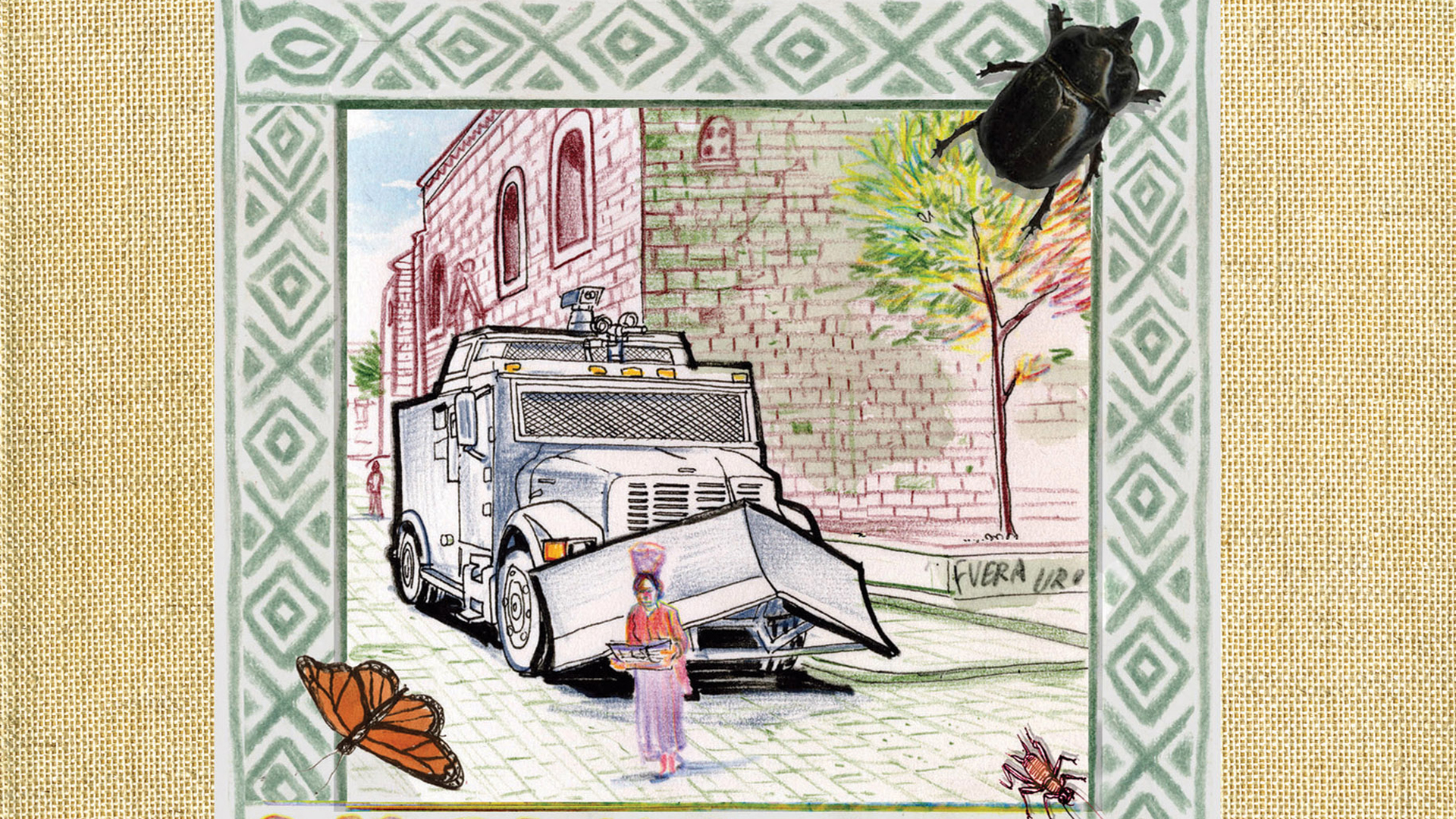

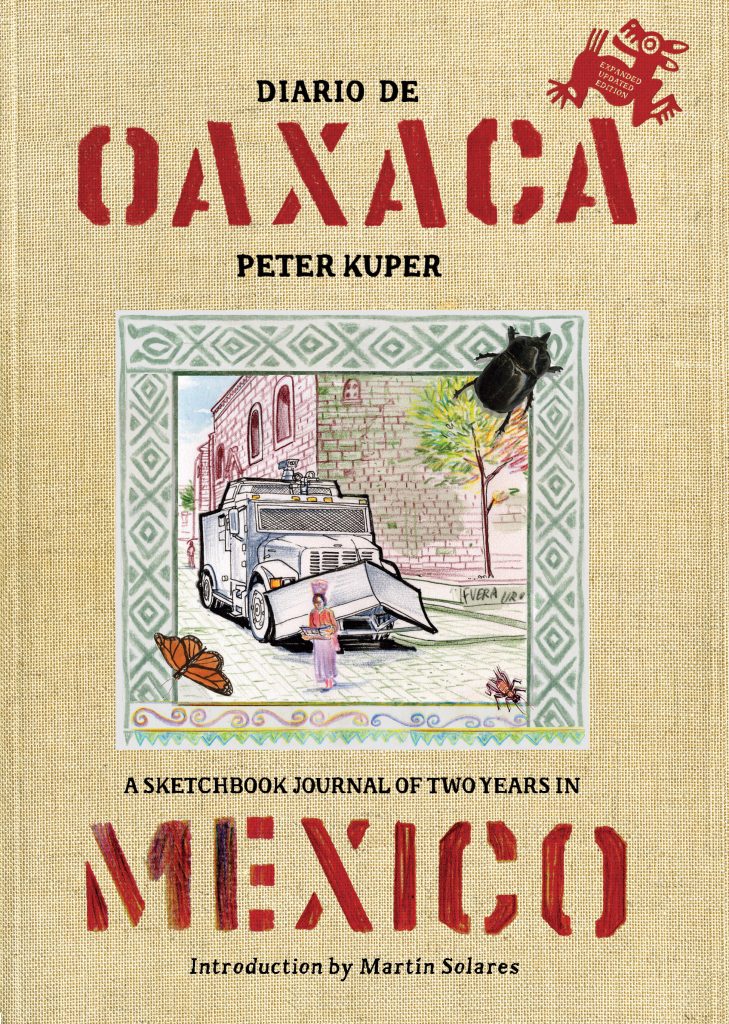

Kuper and his family were in Oaxaca through the most tumultuous days of 2006 and 2007 and he kept a remarkable sketchbook diary. The full title is Diario de Oaxaca: A Sketchbook Journal of Two Years in Mexico. Mostly pictures, it is perhaps 15% text, and the text is presented in both Spanish and English. Diario is being simultaneously published in Mexico, so there is a practical reason for the bilingual format. The format, however, also demonstrates Kuper’s evident respect for the language and culture of Mexico.

Kuper became a cartoonist imbedded in history. Oddly enough, there is a tradition of cartoonists as witnesses to history. Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Marjane Starapi’s Persepolis, graphic memoirs based on their own familiy histories are well-known. Joe Sacco’s Palestine is first-rate cartoon reportage. Readers should search out the work of the British cartoonist, Ronald Searle, who at age 20 was interned in a Japanese POW camp. Keiji Nagazawa drew Barefoot Gen based on his childhood memories of the atomic bomb blast in his hometown of Hiroshima. These examples, with the exception of Searle’s work, were published in traditional graphic novel format. Kuper’s Diary is not your typical graphic novel, a few pages do contain comic strips, but more overflow with impressions, sketches, color notes, even some photos and photocollages.

Kuper writes, “My eyes constantly watch for new subjects, and drawing in my sketchbook has become a daily obsession.” He describes how his senses became heightened by the experience of being a witness, not just his vision, but his hearing, even his sense of taste and smell.

One might ask, what is the point of sketchbook journalism in a digital age? Fair question. As an illustrator myself, and familiar with Oaxaca, I found Kuper’s diary profound and moving. One day in 2008, when I was in Oaxaca, there was a small demonstration on a street corner. I watched it unfold. David Venegas, a charismatic young radical, was denouncing injustice to about thirty people through a bullhorn. Two blocks to the east, pickup trucks filled with armed riot police were at the ready. A few yards in the other direction was a covey of photojournalists. The photojournalists wore their standard uniform, multi-pocketed khaki vests, shoulder bags, and cameras with enormous telephoto lenses. This was a tiny peaceful demonstration and it ended without incident, nothing like the chaos Kuper witnessed in 2006. An American standing near me gestured toward the press photographers and said, “This will look like a hell of a confrontation in tomorrow’s newspapers. With those telephoto lenses it will look like the police were toe to toe with the demonstrators.” He was right.

The camera’s image, even without Photoshop, can distort the truth. An artist’s sketch, on the other hand, makes no pretense of objectivity. Seeing the actual marks a person makes on a page alongside their written words affords the reader a special insight. We get the sense that we know Peter Kuper, that we are in the company of a friend, and that our friend is a reliable witness to history.

At one point Kuper experiences an earthquake and notes “Living in Oaxaca during the political upheavals of 2006, and seeing how those events were covered by major news outlets, I’ve come to believe that most news is all sizzle without the quake. If we are not witnessing an event first hand, then we have to accept hearsay and a tremendous amount of that hearsay is misinformation and sometimes even outright lies. Yet we clutter our minds and discussions with the endless stream of inaccurate or useless information we receive.”

Kuper’s Oaxaca Diary isn’t news. It is something different, an intense meditation, a fascinating testimony, and work of art.

Buy Diario de Oaxaca: A Sketchbook Journal of Two Years in Mexico: