By Alex Dueben

Comic Book Resources

Peter Kuper is one of the most productive illustrators and cartoonists of the last several decades, in addition to being one of the most politically active. He’s made a mark in many outlets in a wide variety of ways, ranging from his visual style, which even casual fans can easily recognize, to the thoughtful political substance that permeates much of his works.

Kuper has drawn covers for “Time” and “Newsweek,” in addition to contributing to “The New Yorker,” “The New York Times” and “Harper’s.” He co-founded the anthology “World War 3 Illustrated” in 1979 and has been one of the guiding editors and contributors since then. Since 1997, Kuper has been the artistic force behind Antonio Prohias’ comic “Spy vs Spy” for “Mad Magazine.”

Outside of the cartooning world, Kuper has written and illustrated numerous books, including the children’s picture book “Theo and The Blue Note.” His syndicated comic strip has been collected into two volumes, “Eye of the Beholder” and “Mind’s Eye.” He’s adapted Upton Sinclair (“The Jungle”) and Franz Kafka (“The Metamorphosis” and “Give It Up!”) into comics.

Kuper’s many graphic novels, which range in subject from autobiography (“Stripped”) to travel (“Comics Trips”), include “The System” from Vertigo, “Sticks and Stones” from Three Rivers Press, “Speechless” from Top Shelf, and 2007’s “Stop Forgetting to Remember.”

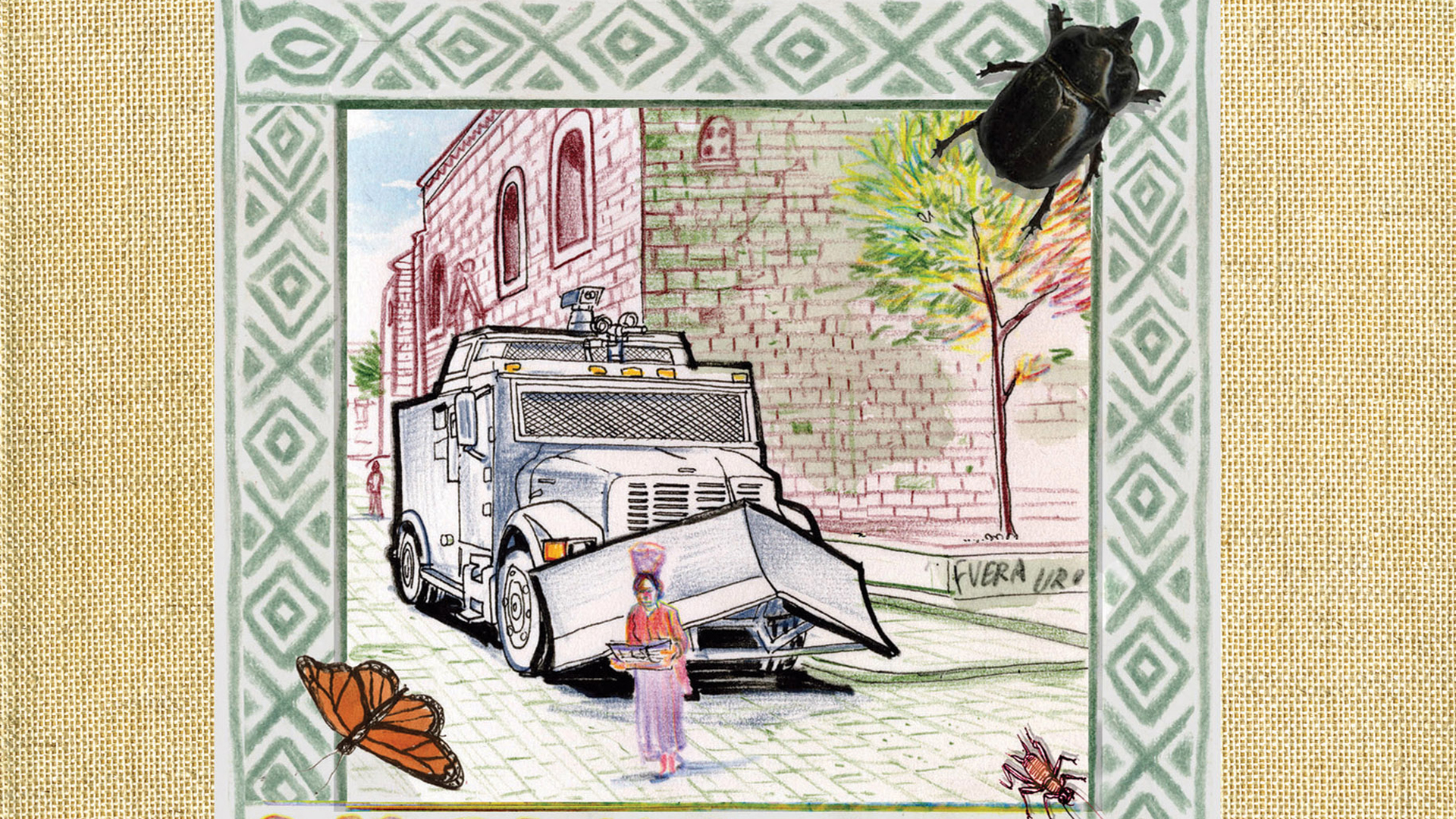

Kuper’s newest book, “Diario de Oaxaca” from PM Press, is a collection of sketchbook pages and diary entries from the year he and his family spent in Oaxaca in 2006 through 2007, a tumultuous time in the city, to say the least. The artist/writer took time out to talk with CBR News about the book and what it was like to live in a very different place than many of those who are fans of his work are used to.

CBR News: Peter, you and your family moved to Mexico for a sabbatical, but why there, and specifically, why Oaxaca?

Peter Kuper: We had first visited Spain. The one constant in our decision was a Spanish speaking country, so our daughter (age nine at the time) would get a useful second language. It was clear we’d have to continue to work at a high velocity if we lived in Europe. Mexico was closer, only an hour off the time zone of NYC, and much cheaper. We picked Oaxaca simply based on a few previous visits. It was a charming 16th century town with plenty of art museums and lots of history.

You mention at one point in “Diario de Oaxaca” that you had visited the area when you were younger. How much had the area changed since then?

It remained unchanged in many ways, except for the traffic. The narrow cobblestone streets were never meant to handle cars and buses, and the number of both had increased dramatically. That and the seven – month teachers’ strike were the big differences.

What was daily life in the city like during the strike? Was it really just business as usual for most of the city outside the zocalo and city center?

It was mostly business as usual, minus the business, since tourism dried up and many hotels and restaurants and all the people that depend on tourism were hurt throughout.

Rereading my journal in our first few months (beginning in July 2006), I noted that concern about Oaxaca being dangerous was not a major subject. Still, that may have something to do with my temperament. My wife says it was scarier than I felt it was.

There were barricades in the streets that required navigation and regular marches, but having lived in New York City for decades it didn’t seem off the charts that there were some streets more dangerous then others.

I don’t mean to minimize the situation. There were some very near misses for us, and many people weren’t so lucky.

A lot of Americans have spent time in Europe or Mexico or other countries where strikes aren’t rare occurrences like here in the U.S., but are rather a fairly common and expected form of labor negotiation. It’s the response, the paramilitary forces and the army being called in, the killing of journalists, that’s hard to picture. How does life go on in the midst of all this?

The people in Oaxaca were incredibly kind and friendly. This is what we were experiencing daily, along with the beauty of the town and fantastic year round weather. We had the good fortune of living away from the town center, so we weren’t confronted with the troubles every time we walked out our door. After Brad Will, the American journalist, was killed and federal troops arrived, it was very different. Walking past tanks and riot police felt like we’d stepped into 1930’s Germany and was very unsettling. Still, we did our work and took our daughter to school – hers was one of the few that remained open – so life did go on, for us at least.

When this happened, what people knew really depended on where they were getting their news. By and large, were people aware of what was going on and why?

People were very aware, but their stories varied and it was hard to know what was the exact truth. Rumors spread easily, so you had to take any info with a grain of salt. Overall, though, people seemed very engaged. Coming from the States, where we knew the president had stolen the election (at least once) and the country had given a collective shrug, to see people willingly encamped in the streets for months and regularly marching against a corrupt politician was inspiring.

At what point did you decide to create a book about your time and your experiences in Oaxaca, and how did you decide upon the format of a combination sketchbook/journal?

It happened incidentally. I had no plan for this. I had been writing for an arts website, DART, and sending drawing out to various publications, including one in Mexico City. They suggested publishing them in a modest way. Like a 64 page book, but they were open to something longer. With that possibility – which came in the last six months of our two-year stay – I began drawing like a man with a mission. Then I realized that the essays I’d been writing for the website would give the book a clearer narrative and fit naturally. I thought it would be fairly easy to assemble, but it took a year of design and printer wrangling to get to the final product.

Why was it important for the book to be in both English and Spanish?

Initially, I thought the book would only be published in Mexico, but I didn’t want people who didn’t know Spanish to be unable to read it.

When I found the American publisher, PM Press, it made even more sense [to present the book in two languages], since we only had to modify a few pages, which made the printing simple and affordable as a co-pub.

Did your habits in Oaxaca in terms of keeping a sketchbook differ from what you do in New York, and have your work habits changed since your time in Mexico?

I’m still sorting through the impact Mexico had on me. The one thing I’ve brought back has been my regular sketchbook drawing. Rarely a day goes by where I don’t put time in filling my sketchbook. I haven’t been anxious to go out looking for illustration work since I am still digesting and can’t pick up where I left off. Having “Diario de Oaxaca” published reminded me to just create as much as possible and hope the publishing opportunities follow.

Was the daily sketching something you did when you were younger and just fell out of the habit of, or is this a new habit new for you?

I have drawn in a sketchbook since high school, and I especially kept one when I traveled. I had a book published in 1992 called “Comics Trips” that was my sketchbook from an eight-month trip in Africa and Southeast Asia.

Before the trip to Mexico I’d fallen out of the habit, but that trip brought me back to that very good habit, and I have continued drawing everyday, religiously since we returned.

“World War 3 Illustrated” is still going strong after three decades of publication. When you started the magazine, did you think it would become this enduring a project and would encompass so much?

We didn’t think in terms of making it endure, though we’re thrilled that it has. There just kept being new subject matter that made us want to create in reaction. Bush certainly gave us a ton of reasons to want to respond through the magazine. He gave us way too much material!

Are you involved in the upcoming issue of “WW3,” and what can we expect from it?

Having edited the last issue, which took on and off seven months, I’m taking a break, but it is moving forward full speed with Seth Tobocman and several others editing as we move into our 30th year of publication. The theme is “solutions,” but as is the tradition of the magazine, what people are dealing with is more about the problems. Solutions don’t come so easily.

A solutions issue seemed appropriate after so many years of writing and drawing about problems. I’m not editing this one since I did the last one, so I can’t yet say whether in this issue we come up with solutions to all the world’s problems.

You wrote in your diary about wanting to continue taking longer lunches and enjoying siestas. Since returning to New York, have you been able to follow through with this desire?

In this economy? Are you kidding? Most of the longer lunches are due to unemployment and hence less enjoyable!

Speaking of the economy, one of the other big projects you’re known for is “Spy vs Spy.” With “Mad Magazine” now publishing less frequently, do you have any thoughts on what it means in the scheme of publishing everywhere seeing a decline?

This is a hard time for magazines, and this is another example of the downturn. There are some seismic shifts going on in the publishing world, but I hope that new avenues will open up to replace the old ones that are disappearing. Being a cartoonist, doing what I enjoy as my job is a privilege. That it is challenging to make this a career isn’t surprising. In a field like this, the sand is always shifting under your feet and it requires moving even to stay in the same place. I’m pretty restless anyway, so I’m looking for a different place to take my work. My next project may be building sand castles…

Buy Diario de Oaxaca: A Sketchbook Journal of Two Years in Mexico: