Kuper’s hardcover opus Diario de Oaxaca, excerpted briefly in Wordless Worlds, is not as distant as it might appear at first glance. Peter Kuper is probably stuck with his best known credit, “Spy vs Spy” in Mad magazine, at least until this publication (in its second half-century and now reduced to quarterly appearance) goes out of business. Kuper inherited the spy piece from another era of Mad, and it has been noticeably wordless all these decades (Kuper took over it over in 1997). The author of arguably the only pantomime strip in widely-distributed comic art, Kuper explored the wordless form throughout his career in graphic novels like The System and Sticks and Stones. With Diario, his sketchbook journal from two years of living in Mexico, he is the observer removed not by silence so much as a keen awareness of his personal status: as visitor.

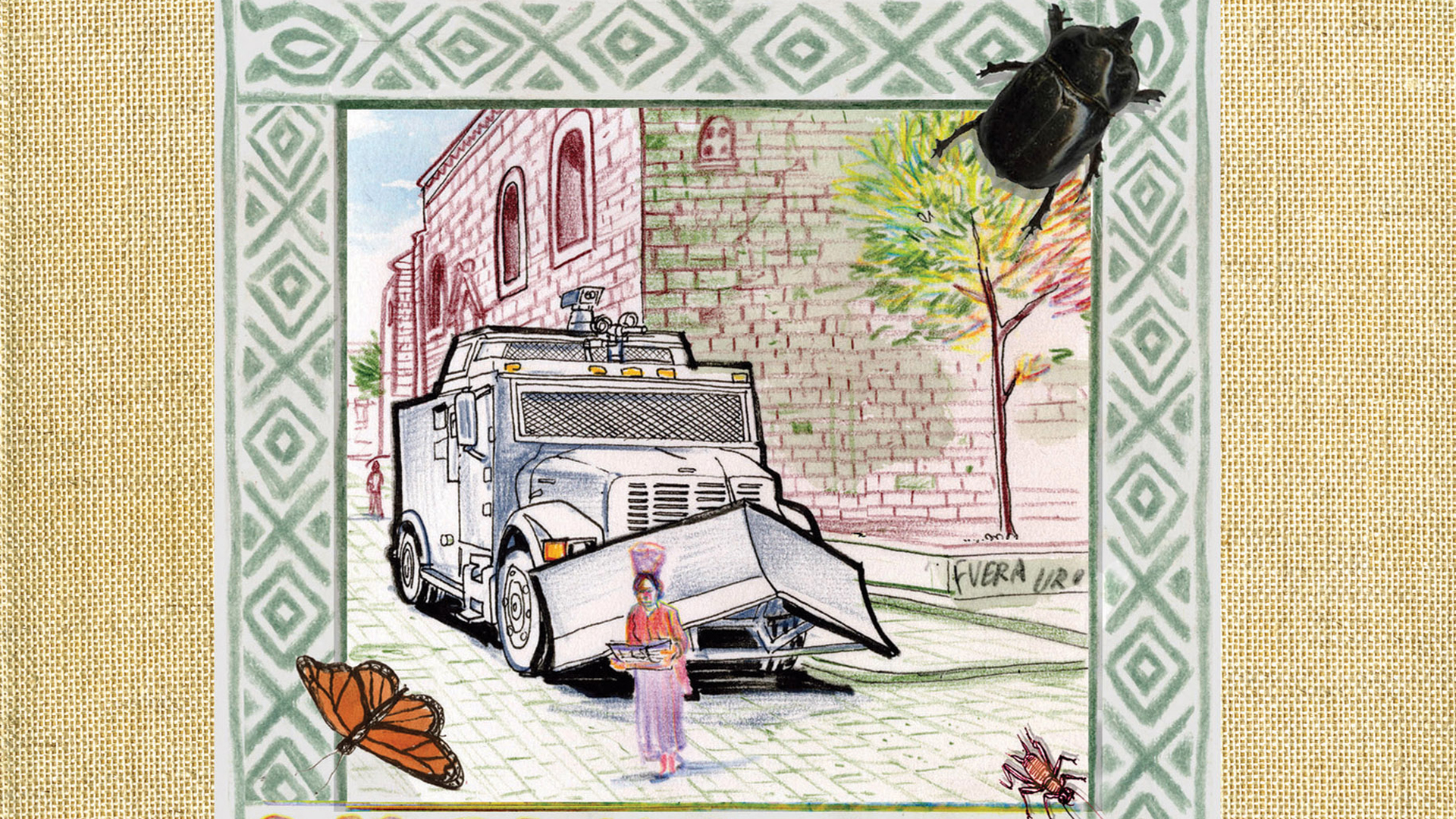

He is not a tourist exactly. He came to Oaxaca (pronounced Wa-Ha-Ka) in 2006 with his wife and child to take a sabbatical from the Bush-administered United States, as well as to broaden a young daughter’s linguistic skills and sensibilities. It just so happens that earth-shaking developments sweep through the city while he is there: the struggles of Oaxacans against a staggeringly corrupt government, seeking decent wages for public service, turn into class and cultural warfare. Kuper might almost have been the Courbet of the modern Paris Commune, but this uprising is crushed with great violence and dozens of casualties, including American journalist Brad Will. Kuper captures the dramatic events through his writing, drawings, and photos as they unfold, as well as when the city returns to its status as tourist center for foreigners seeking a warm, relaxing good time, close to archeological sites of lost civilizations. During the interim, all kinds of rebellious art and artistic graffiti appears on city walls, some of it reproduced here in drawings and photographs, while he sketches his own family’s daily lives, with equally heavy emphasis on natural surroundings.

Throughout, Kuper demonstrates his fascination with insects, not only the Monarch butterflies (whose breeding grounds are nearby) but also bugs of every variety. From stinging scorpions to corrupt politicians, Kuper draws parallels between the natural beauty and the dangerous reality that Mexicans encounter every day. The insects represent the “jungle of freedom” of the surrealist world view, the proliferation of life forms absent in Western cities but so much a part of homo sapiens’ transhistorical experiences—that is, of the species launched in the hot climates only gradually advancing to colder places.

The wondrous character of the sketches is in no small part their color, as it overflows with the sampling of Mexican art of everyday life. Understandably, the “Day of the Dead” makes a huge impression on the artist, but so do Aztec memories, the masks of assorted celebrations, the colorful dress, the omnipresent dogs, the occupying soldiers armed against an unarmed population, endangered sea turtles, professional wrestlers, pyramids, and other highly assorted phenomena. One is tempted to say “All in Living Color”—but of course, the Dead are among the most vivid inhabitants, and the long-dead civilizations as well. In any case, this is an artist-traveler’s notebook to cherish and flip through almost endlessly. Each visit to its pages will bring the reader some new gift.

Buy Diario de Oaxaca: A Sketchbook Journal of Two Years in Mexico: