When Saturday Comes Magazine

by Tom Davies

October 2011

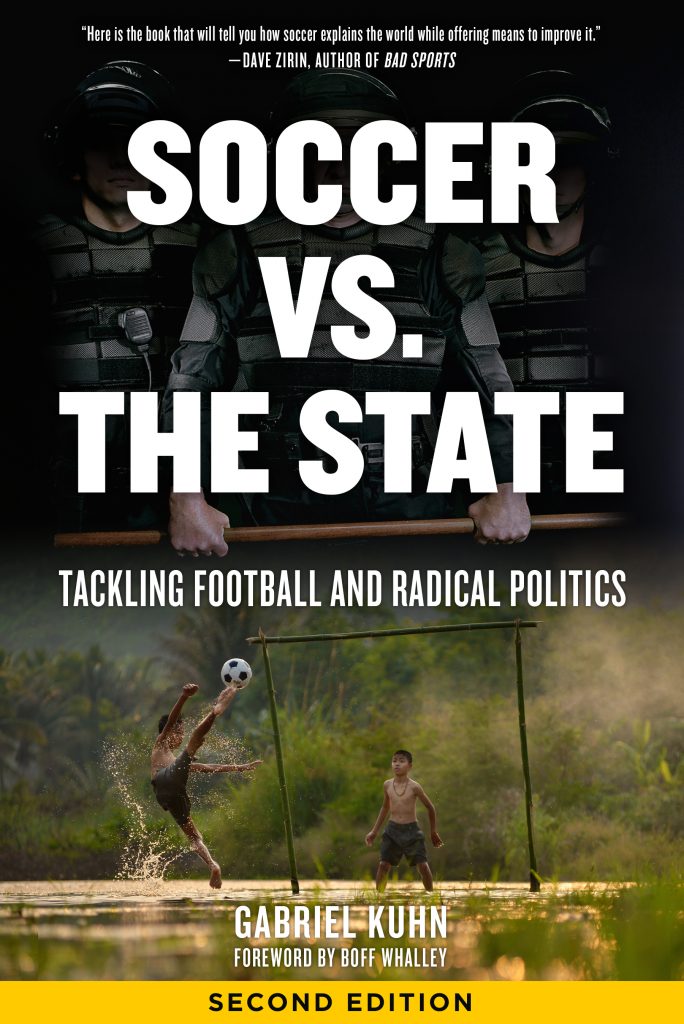

The idea that football and politics cannot or should not mix has always been convenient nonsense. Both continually rub up against and influence each other, without either quite managing to bend the other to its will. The question of how football has been approached politically is addressed here- from an unashamedly leftist perspective- by Austrian activist and one time semi-pro playa Gabriel Kuhn in this collection of essays, interviews and excerpts from journals and pamphlets, interwoven with commentary from Kuhn himself.

There has always been a tension on the left between those who have dismissed football as a counter-revolutionary distraction from The Struggle and those keen to stress its social potential. Kuhn, mercifully, is on the latter side, without being blind to the game’s limitations and dangers. Kuhn is impressive in his global and historical scope, and in acknowledging gender and sexuality questions as well as those of class and race, as he looks at issues ranging from the exploitation of African players to the way the World Cup has been abused politically (varying from the Argentinian junta’s outrages in 1978 to FIFA’s commerical juggernaut parking on South Africa in 2010).

Genuinely interesting, too, are the sections on politically engaged players, such as Livorno’s local hero Cristiano Lucarelli. There’s also the links between Internazionale and the Zapatistas driven forward by Javier Zanetti. The letter from the Mexican rebels’ leader Subcomandante Marcos to Inter is published in full here, packed as it is with entertainingly extravagant demands. (A match in Cuba? Another one in the Basque country? Another involving Mexican transexuals?)

The book posits itself throughout as against the consumerism and iniquities of the “New Football Economy”, inextricably linked as they are to the past two decades’ political neoliberalism, while wisely counsling against responding with backward-looking traditionalism. “It is problematic to claim that the rapid commercialisation of the game during the last decades has ‘stolen’ the game from the workers —the game was never fully theirs,” writes Kuhn.

Kuhn tackles some, though not all, of the myths that have grown up around clubs with political associations. St Pauli’s radical following and traditions are not matched in the way their club is run. Barcelona may be a member-owned club with historical links to the fight against Franco but they are also gorging themselves on the imbalances of the New Football Economy. And the invoking of the Celtic’s radical credentials may be met with eye-rolling by some in Scotland. In contrast, we’re also introduced to those who have applied their politics to football outside its traditional structures. Bristol’s Easton Cowboys offer a fascinating study in how running a democratic community football club can reach the parts staid political organisations cannot.

Perhaps because the book jumps around somewhat, and covers so many different questions, it lacks any detailed analysis on how radical fandom can coherently confront modern football’s power structures. FC United of Manchester, AFC Wimbledon and others are given their dues, but themes of supporter democracy are not fully developed.

This is ultimately because Soccer Vs. The State comes across as a book for politicos looking to understand football, rather than vice versa. But for those of us who could happily chew the fat about both for hours at a time, it is still informative grist to our mill, and upbeat about the game’s potential. As the author writes in conclusion: “If Emma Goldman wants to dance in her revolution, others should have the right to kick a ball around.”