By Bill Berkowitz

Truthout

January 9th, 2016

The Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, located at Ferris State University in Big Rapids, Michigan, contains thousands of items of despicable racist ephemera – mostly, but not entirely, emanating from the era of Jim Crow – but has as its overarching goal the promotion of racial understanding and the improvement of racial relations. While the museum’s displays mostly come from the era of Jim Crow, museum officials emphasize that negative caricatures of Black people did not end with that period. A large display of racist objects produced in the 21st century demonstrates the ways in which Jim Crow-era attitudes and behavior continue to exist.

Nevertheless, the majority of the museum’s grotesquely racist artifacts date back to the Jim Crow era. They include a 1930s party game called “72 Pictured Party Stunts,” which includes a card depicting a dark Black boy with bulging eyes and blood-red lips eating a watermelon as large as he is and instructs players to “go through the motions of a colored boy eating watermelon?” Other racist memorabilia include the “N***** Milk” cartoon, in which a sweet, little Black baby is suckling out of an ink jar, countless mammy renderings on salt and pepper shakers, and postcards of Black people being whipped and hanging from trees.

The racist memorabilia in the museum was all collected over the past three decades by David Pilgrim, an African-American former sociology professor who has devoted his adult life to raising awareness about racism through the museum and its traveling exhibits. In addition to founding the museum, Pilgrim is a filmmaker, who in 2004, produced – with Clayton Rye – the award-winning documentary, Jim Crow’s Museum, to explain his approach to battling racism.

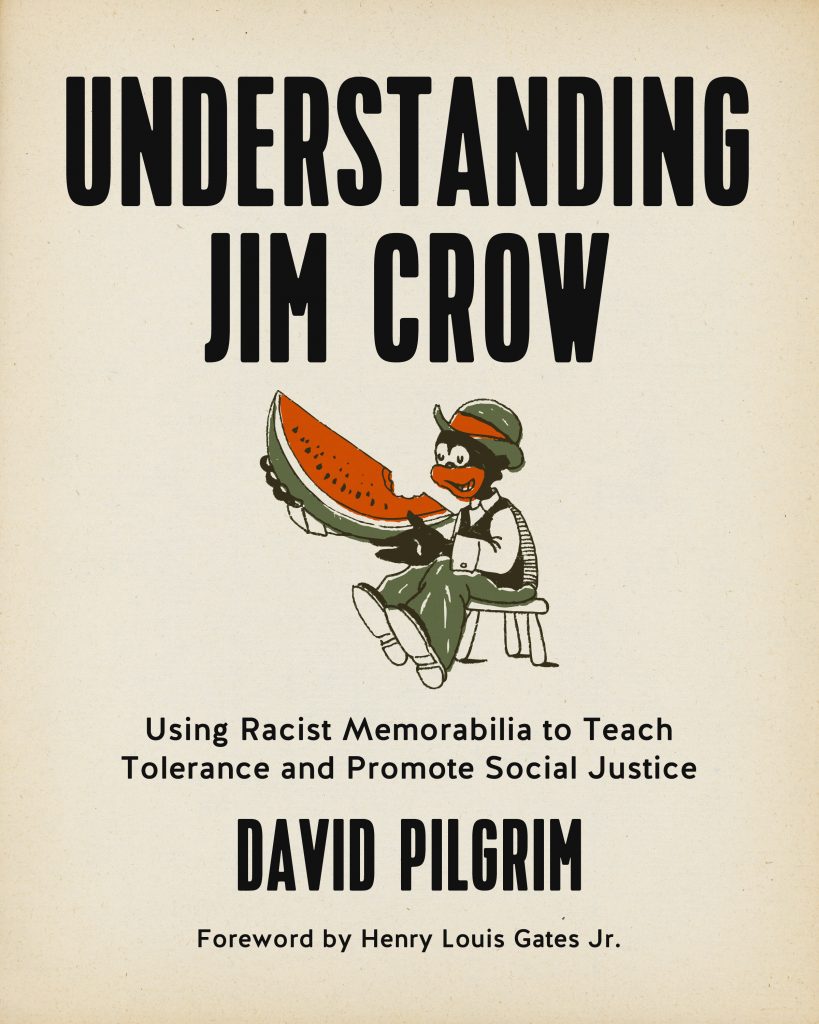

Early on in his book, Understanding Jim Crow: Using Racist Memorabilia to Teach Tolerance and Promote Social Justice, Pilgrim identifies himself as “a garbage collector,” as he has painstakingly, and often emotionally painfully, gathered thousands of items “that portray blacks as coons, Toms, Sambos, mammies, picaninnies, and other dehumanizing racial caricatures.”

Pilgrim’s collection contains “items that defame and belittle Africans and their American descendants.”

The Jim Crow Museum is curated to guide visitors through developing a deeper understanding and critique of the many violent ways in which Black people have been caricatured. (Photo: David Pilgrim/PM Press)

Pilgrim

didn’t go to garage sales, visit flea markets and later use the

internet to buy memorabilia merely to build his personal collection,

auction it off or resell it on eBay. Nor was he sitting at home hoarding

his collection. And, most of all, he didn’t collect scads of repugnant

artifacts in order to remove them from plain sight. In fact, Pilgrim

believes that “items of intolerance can be used to teach tolerance and

promote social justice.”

Pilgrim bought his first racist

object (a mammy salt shaker, which he immediately smashed) at age 12 or

13 in Mobile, Alabama, the home of his youth. Collecting racist objects

eventually turned into the obsession that evolved into Pilgrim’s

essential project: the founding and curating of the Jim Crow Museum of

Racist Memorabilia, which houses the nation’s largest publicly

accessible collection of racist artifacts.

If, as a character in Darrin Bell’s comic strip “Candorville” put it, “sometimes your outrage muscle needs a rest,” then Pilgrim’s book on understanding Jim Crow, which presents the message and contents of his museum in book form, might not be for you.

The images displayed in the book certainly are vile and hateful, carefully crafted to elicit the racist ideas that their creators wanted their fellow Americans to perceive, understand and internalize.

As Henry Louis Gates Jr., Alphonse Fletcher University professor at Harvard University, points out in the foreword to the book, “Racist imagery essentializing blacks as inferior beings [in Jim Crow’s United States] was as exaggerated as it was ubiquitous. The onslaught was constant.”

And despite African Americans pulling off “a miracle of human history, of enduring centuries of bondage to claim their freedom,” Gates writes, “Jim Crow’s propaganda … was exhausting,” and pervasive in the culture. “There was nothing understated about Jim Crow.”

Pilgrim’s thoughtful and passionately told story makes the book more than just another, albeit unique, history of US racism.

Pilgrim recognizes that “All racial groups have been caricatured in this country, but none has been caricatured as often or in as many ways as have black Americans. Blacks have been portrayed in popular culture as pitiable exotics, cannibalistic savages, hypersexual deviants, childlike buffoons, obedient servants, self-loathing victims, and menaces to society.” As Robbin Henderson, former director of the Berkeley Art Center, has said, “Derogatory imagery enables people to absorb stereotypes, which in turn allows them to ignore and condone injustice, discrimination, segregation and racism.”

Understanding Jim Crow contains images of racist book covers, cereal and soapboxes, dishes, endless sets of postcards, greeting cards, records, minstrel joke books and sheet music, and other examples of racist memorabilia. However, it is Pilgrim’s thoughtful and passionately told story that makes the book more than just another, albeit unique, history of US racism. Essentially, the book is about Pilgrim’s dedication to turning garbage collecting into tools for teaching about racism.

As a graduate student at Ohio State University, Pilgrim started buying items he could afford, paying a couple of bucks for “a postcard that showed a terrified black man being eaten by an alligator,” and “for a matchbook that showed a Sambo-like character with oversized genitalia.” By the time he joined the sociology faculty at Ferris State University, his collection – still housed at his home – contained more than a thousand items, some of which he brought to public appearances, mainly at local high schools.

In 1991, Pilgrim managed to see the collection of an elderly Black antique dealer in a small town. After promising not to “pester” her to sell the objects, she closed the shop door, put the “closed sign in the window, and motioned for me to follow,” Pilgrim writes.

“If I live to be a hundred,” Pilgrim continues in the book, “I will never forget the feeling I had when I saw her collection; it was sadness, a thick, cold sadness. There were hundreds, maybe thousands, of objects, side by side, on shelves that reached to the ceiling. All four walls were covered with the most racist objects imaginable.” Although Pilgrim already owned some of the items he saw, he was “stunned” by “every conceivable distortion of black people, our people, [that] was on display.”

That moment, filled with sadness, disgust, anger and outrage, led Pilgrim to decide to create a museum. And five years after the visit to the elderly Black woman’s antique shop, the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia opened at Ferris State University.

Understanding Jim Crow is far from being an angry book. But it is disturbing and uncomfortable. It is as James W. Loewen, author of Lies My Teacher Told Me, wrote in a blurb, a unique effort “to bring out from our dank closets the racial skeletons of our past.” However, judging from the numerous racist images that have popped up in all sorts of venues during the years of the Obama presidency, this historical study also hangs onto the present.

Pilgrim describes the museum he created as a place that “use[s] items of intolerance to teach tolerance and promote social justice,” by “examining[ing] the historical patterns of race relations and the origins and consequences of racist depictions.”

As Pilgrim points out, “The twenty-first century has brought a fear and unwillingness to look at racism in a deep systematic manner.” Many Americans prefer to “forget the past and move forward.” Nevertheless, in an age of more awareness of police brutality, presidential candidates like Donald Trump stirring up racial animus, “[r]acial stereotypes, sometimes yelled, sometimes whispered, [continue to be] common.”

Three years ago, the Jim Crow Museum moved into larger headquarters, which allowed for the integration of stories of “accomplishments of black artists, scholars, scientists, inventors, politicians, military personnel, and athletes who thrived despite living under Jim Crow.” A civil rights movement section has also been added.

While cautiously optimistic about the future, Pilgrim refuses to downplay the past or ignore the present. The museum’s website has a section called “… and it doesn’t stop,” which features examples of blatantly racist objects that are still being created.

The United States has never had a truth and reconciliation commission to deal with the country’s racial divide. Yet we always seem to be in the midst of some sort of discussion about race, a discussion that frequently gets blown off course, and winds up going nowhere and achieving little. Henry Louis Gates Jr. calls the Jim Crow Museum, a “truth and reconciliation commission, formed out of the detritus of Jim Crow, with an interpretive story encasing it that would help witnesses state down the grotesqueries and, through a shared experience, confront hard truths.”

The mission and tagline of the Jim Crow Museum is deceptively simple: “Using Objects of Intolerance to Teach Tolerance.” Unfortunately, the production of racist caricatures of Black people did not end with the Jim Crow era. “Blatantly racist objects,” like shooting targets depicting Trayvon Martin, were sold in the aftermath of his murder in 2012, Pilgrim points out. There is still much work to be done.