By Paul Von Blum, JD

Journal of Pan African Studies March 2017, Vol. 10 Issue 1, p382

For many years, in my UCLA classes and in presentations throughout the United States and the world on African American art, I have started with several examples of egregiously racist images from popular culture. From the thousands available, I often select such repulsive examples as “Darkie Toothpaste,” “Nigger Head Golf Tees,” and minstrel-like items from the Coon Chicken Inn, a fried chicken restaurant chain in the Pacific Northwest from the 1920s through the late 1940s. These grotesque racist caricatures are the visual foundation for my long-standing argument that African American art, in substantial part, constitutes an effective body of resistance to the dominant narrative of American history that conceals or understates the political and human implications of slavery and its progeny.

For my student and other audiences, I regularly recommend the Jim Crow Museum of Racism Memorabilia at Ferris State University in Big Rapids, Michigan. This remarkable museum is the largest publicly accessible collection of racist artifacts. It consists primarily of memorabilia from the segregation era from the South, although many of the objects were distributed and widely available throughout the entire country. The chief objective of the museum is to highlight these objects to foster dialogues and understanding of historical and contemporary racism in America. It is an invaluable resource for scholars, journalists, and activists.

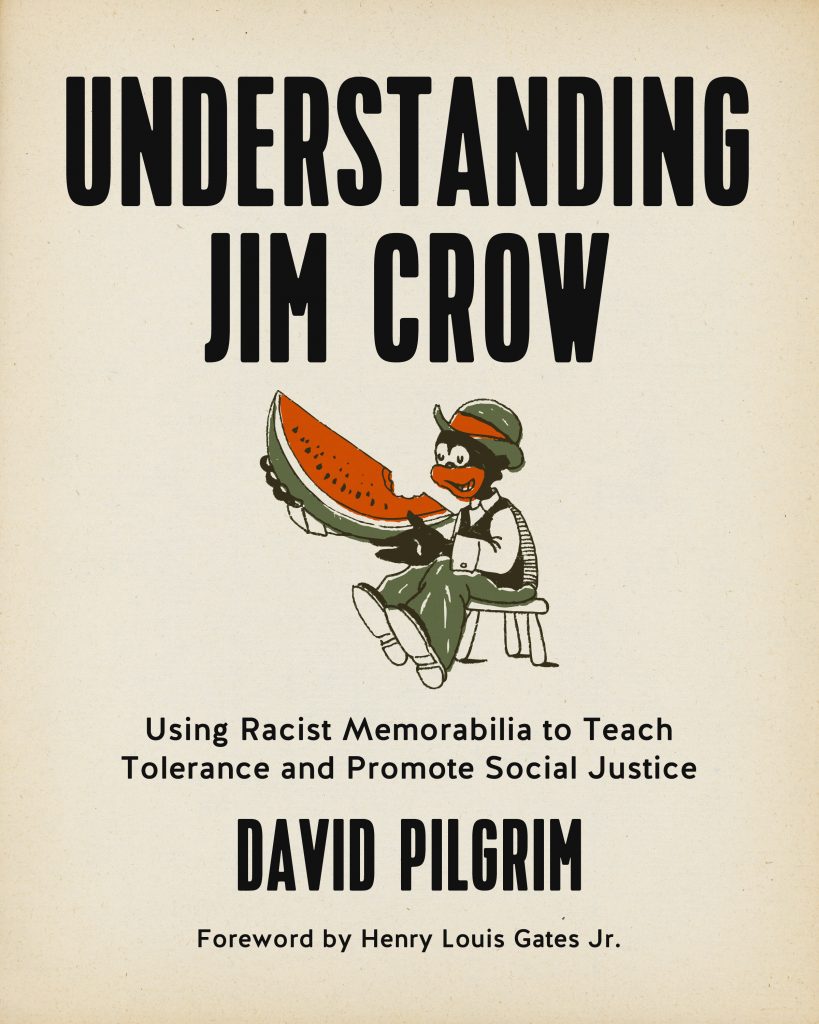

Understanding Jim Crow represents the Museum in book form. This is especially useful for readers who are unlikely to make a trip to Michigan to see the collection in person, however valuable such an experience would be. The volume contains several outstanding components, making it a splendid contribution to African American Studies and many cognate fields. Like the Museum itself, the book should attract multiple audiences, from academic specialists to lawpersons.

At the outset, the author, David Pilgrim, chronicles the personal story that was the genesis of the museum he founded. He grew up in the Deep South as that region began to transform from its overt segregation to its more benign but still institutionally racist environment. Chapter One is intriguingly titled “The Garbage Man: Why I Collect Racist Objects.” Professor Pilgrim details his life story that catalyzed his desire, indeed his obsession, to collect the racist objects that later developed into the museum he founded.

As an undergraduate student at Jarvis Christian College, a small historically black institution, he learned from his professors what it meant to live as African Americans in a rigidly segregated society. It involved surviving as second-class citizens in every detail of daily life, where racial inferiority was understood and regularly enforced. Pilgrim began to see the close connections between racial oppression and the ways that Blacks were portrayed in popular culture as buffoons, apes, savages, and sexually voracious idiots and monsters.

This recognition impelled him to collect artifacts that reflected and reinforced this racist system. As a graduate student at Ohio State University, he acquired many items, mostly inexpensive, and he developed a deeper appreciation of his African American identity and obligation to work on behalf of his people. He credits his graduate school encounter with Paul Robeson’s Here I Stand as a major source of his consciousness.

In 1991, he visited an elderly Black woman who had a large collection of Jim Crow related objects. Seeing her massive collection, Pilgrim was appalled at the pervasive distortion of African Americans he discovered there. He describes it as a chamber of horrors, but he continued to visit her until her death. Those experiences reinforced his desire to continue purchasing and collecting racist objects, including musical records with racist lyrics, children’s games with dirty and naked Black children, items with Sambo imagery, and anything else he could personally afford. This was the genesis of the museum at Ferris State University after he became a member of the Sociology Department faculty there.

Much of the text of Understanding Jim Crow consists of an analytical treatment of the stereotypes deployed against African Americans over the years. He addresses the common stereotypes including mammies, Toms, picaninnies, tragic mulattos, jezebels, coons, brutes, bucks, and others that a racist society has created and perpetuated throughout its history and popular culture.

His treatment covers most of the popular culture forms, including films and television. Pilgrim’s treatment of television’s use of racist caricatures for well over half a century, in fact, is a damning indictment of the medium that hundreds of millions of people watch on a daily basis.

His account is a powerful complement to Donald Bogle’s Toms, Mulattoes, Mammies, & Bucks, the iconic history of Blacks in American film. The present volume is richly illustrated with examples drawn from the Museum’s collection. These images are mostly shocking and disgusting; they add a dramatic visual presence to the specific textual analysis that the author elaborates in his book. They vary in content and include examples that are merely stupid caricatures of Black men, women, and children to thoroughly grotesque images of lynchings and depictions of African Americans as animals.

The common element is that these depictions normalize millions of human of African descent as entirely inferior beings. The central point is that these images, disseminated repetitively, lead the majority population to reinforce and rationalize their destructive attitudes and their conduct toward their fellow human beings. Popular culture is not a trivial adjunct to the course of history; rather, it plays a central role in producing and perpetuating the patterns of oppression that have scarred and despoiled our history for four centuries. That realization is the most significant theme emerging from this important book.

Understanding Jim Crow also has two other features that contribute to its overall excellence. The first is an insightful Foreward by Harvard Professor Henry Louis Gates. Gates’s essay discusses the meaning and impact of a museum devoted to presenting the stereotypes of Black people as shiftless, guileless, terrified, conniving, and other horrific clichés that have dehumanized them over the centuries. He acknowledges his initial misgivings about visiting the museum and his understandable reaction that some of the objects understandably “turn the stomach.”

But Professor Gates makes an especially important point about why the Jim Crow Museum is such an invaluable resource. He acknowledges that some or even all of these memorabilia might unwittingly contribute to the brainwashing of actual and potential racists and might normalize violence through repetition in that setting, despite the warnings from the wall text and museum guides. Gates argues persuasively, however, that these racist objects can actually promote a healing power and engender a new commitment for anti-racist action.

He makes the case effectively: “Instead, by confronting our fears, we learn to master them, and from that learning comes the wisdom to see a nemesis like Jim Crow for what it really was––a systematic attempt to undermine a people, by framing and justifying, their second-class status. . . .”

We need not hide from these racist signs and objects. Instead, we need to expose them to the light of day in order to have a fuller if more disconcerting sense of the past. Then––and only then––can America move towards genuine equality and racial justice.

The final segment of the volume is the most engaging. It reproduces a colorful mural by African American artist and Ferris State University professor Jon McDonald. Entitled “Cloud of Whiteness,” the 2012 artwork in the Museum features a moving tribute to some of the people who sacrificed their lives during the Civil Rights Movement era. This striking mural complements perfectly the disgraceful imagery in the Museum itself. Like the objects in the collection, it also encourages viewers to probe deeply and reinforce collective memory about recent U.S. history.

Seventeen figures of Black and White victims of racial violence are pictured in the clouds, hovering over the landscape. Their faces, situated in the heavens, look down upon the earth. They remind audiences that they gave their lives in the eternal struggle for freedom. Many of these figures are well known and have dramatically entered the annals of recent historical memory. Iconic leaders like Dr. Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and Medgar Evers, all of whom were assassinated in the prime of their lives, are prominently displayed in this magnificent mural.

So too are other significant martyrs from that era, who are generally well recognized among civil rights activists and historians: James Reeb, the white Unitarian Universalist minister who died after being savagely beaten by racist white men in Selma, Alabama in 1965; Viola Liuzzo, a wife and mother from Detroit who was shot to death by Klansmen while transporting civil rights marchers between Selma and Montgomery, Alabama in 1965––she was the only white woman martyred during that era; and Michael Schwerner, James Earl Cheney, and Andrew Goodman, who were tortured and murdered by Klansmen following their bogus arrest in Mississippi in 1964.

Still others pictured in McDonald’s mural also paid the ultimate price, but their specific names have never had the name recognition of the other martyrs in the artwork. On September 15, 1963, Ku Klux Klan members bombed the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, just a few weeks after the historic March on Washington. Although this horrific event galvanized national attention on racist violence in America, few people now remember the names of the four young girls who died in that bombing: Denise McNair, Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, and Carole Robertson. The mural memorializes them and reinforces the reality that racism is no abstraction, but rather a malignant force that can kill real human beings.

Finally, this powerful artwork highlights four other African Americans who lost their lives and who are not on the public radar: Johnnie Mae Chappell, a wife and mother who was murdered in 1964 in Jacksonville, Florida when several young white men, during a period of racial tension, decided to “get a nigger”; and Delano Herman Middlelton, Samuel Ephesians Hammond, and Henry Ezekiel Smith, African American teenagers killed by police during a civil rights protest in 1988 in Orangeburg, South Carolina. They too join the others and achieve a level of immortality through this brilliant example of public mural art.

“Cloud of Whiteness” makes perfect sense in the setting of the Jim Crow Museum because it encourages visitors to understand that racist popular culture is inextricably linked to racist violence. Above all, it encourages a deeper understanding that resistance is the hallmark of African American history. The book itself effectively underscores that message. The recognition of the power and significance of resistance, at the dawn of the Donald Trump administration in 2017, has never been more important for all people of goodwill.